Breaking up the Habsburg Empire↑

Pre-War Career↑

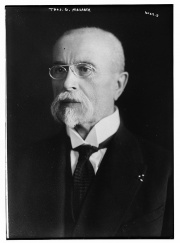

In 1914, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (1850-1937), who took his second name from his American wife Charlotte Garrigue (1850-1923), already enjoyed a certain degree of prominence in Austria-Hungary and abroad as both a scholar and a politician. He had been a professor of philosophy at the Charles University in Prague since 1897. From 1891 to 1893 he represented the Young Czech Party in the Reichsrat (the Austrian Parliament) and from 1907 to 1914 he represented the small Česká strana pokroková (Czech Progressive Party, also known as the Realist Party) that he had founded in 1900.

Masaryk’s opinions and actions were often considered unorthodox and inconvenient by the political mainstream. Against general opinion of the time, he argued that two allegedly medieval Czech epic poems were in fact counterfeits; in 1897, he wrote several newspaper articles defending a Jew who had been wrongly convicted of a ritual murder and thereby achieved the case’s reopening. He also sharply criticized the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1908 and, interfering in a trial for treason and conspiracy, was able to prove that the Austrian authorities had produced forged documents against the Croatian defendants. His contacts to Southern Slavic politicians proved useful during the war.

Revolution from Abroad: Fundraising, Propaganda, Troops, Ideology↑

When the war broke out, Masaryk, who for some time had hoped for the democratization and federalization of Austria-Hungary, began planning to achieve Czech independence by breaking up the Habsburg Empire from abroad. In December 1914, he went into exile via Rome to Geneva. Before his departure he founded an organization of Czech politicians plotting an anti-Habsburg conspiracy called – with intended irony – Maffie, that is Mafia. Through its couriers, Masaryk was able to stay in touch with important Czech politicians in order to influence politics at home and get inside information on the situation in Austria-Hungary.

Apart from these connections, Masaryk was in many respects well prepared to lead the revolution from abroad. He had already won a considerable reputation on the international level; he was familiar with the United States of America (he was a visiting professor at the University of Chicago in 1902) and Russia, including the Czech colonies there; and he had influential friends who helped him win over British and American journalists and politicians for the Czechoslovak cause. The historian Robert William Seton-Watson (1879-1951) not only facilitated Masaryk’s appointment as professor of Slavonic studies at the King’s College London, but as editor of the influential weekly The New Europe he also provided Masaryk the opportunity to present his program of a new Europe, where, after the breaking up of the Habsburg Empire, the small nations situated between Germany and Russia would be able to establish new independent states.

Other instrumental friends included the Times journalist Henry Wickham Steed (1871-1956) and the American industrialist Charles Richard Crane (1858-1939), who in 1918 arranged a personal meeting between Masaryk and US President Woodrow T. Wilson (1856-1924). On 14 November 1915, Masaryk, as head of the Czech Committee Abroad, published a manifesto proclaiming the independence of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown (Bohemia, Moravia, Austrian Silesia) and the regions of the Kingdom of Hungary inhabited by Slovaks. Together with his closest collaborator, Edvard Beneš (1884-1948), who had followed him into exile in September 1915, and Milan Rastislav Štefánik (1880-1919), a Slovak officer serving in the French army, Masaryk established the Czechoslovak Foreign Committee in Paris in February 1916. Its main tasks were propaganda, fundraising amongst Czech and Slovak colonies abroad and negotiations to establish Czechoslovak armed forces (called Legions), which were to consist mainly of Czech and Slovak prisoners of war. While Beneš, the Committee’s secretary general, worked from Paris, Masaryk, the Committee’s undisputed leader, and Štefánik spent many months in 1917-18 on long journeys to further their cause.

From May 1917 to April 1918 Masaryk spent almost a year in Russia, building up a Czechoslovak army, which was then to be transferred to the Western Front in France. This was made possible by the Russian revolutions in March and November 1917. In negotiations with the Bolsheviks, Masaryk declared the Czechoslovak Legion’s armed neutrality and its non-interference in the civil war and in turn demanded its unhindered transfer to France. In spite of this, after Masaryk had left via Siberia and Japan for the United States, the Legion became involved in the civil war. Since the Legion temporarily controlled the Trans-Siberian Railway and looked for guidance to the Czechoslovak National Council, it became the Council’s trump card in the 1918 negotiations with the French and British concerning the recognition both of independent Czechoslovak troops and of the Provisional Czechoslovak Government. As the US government was keenly interested in Masaryk’s expertise on Russia’s present state and future development, he mostly stayed in Washington from April to November 1918. On 30 May 1918 he signed, together with American Czech and Slovak representatives, the later disputed Pittsburgh Agreement on building a common state. In his summarizing 1918 publication, The New Europe, Masaryk interpreted the world war as a struggle between progressive humanitarian democracy (the Entente and the United States) and despotic theocracy (the Central Powers). This well-known substantial contribution to Allied war philosophy and ideology helped him win over President Wilson and large parts of the US public for the Czechoslovak cause. In the Washington Declaration on 18 October 1918, the Czechoslovak National Council declared itself a Provisional Government, consisting of Masaryk (prime minister, finance), Beneš (foreign affairs, interior) and Štefánik (war). Allied recognition followed immediately. In December 1918, Masaryk returned to Prague as president of the newly-founded state.

Post-War Career and Image↑

On 14 November 1918, the National Assembly in Prague elected Masaryk as president of the Czechoslovak Republic. He was reelected three times, in 1920, 1927 and 1934. On 14 December 1935 he resigned due to his age and increasingly poor health. The so-called President-Liberator is still held today in high regard in the Czech Republic, and in part in the Slovak Republic. He is considered the founding father of the new state and a personification of democracy. This is partly an echo of a leader cult that developed in the interwar-period, when the media close to the “Castle” (Masaryk’s and Beneš’s political camp) depicted him as a flawless democrat and moral authority, a (democratic) philosopher king, a great statesman, and a political thinker of European or even global importance, impartially watching over his state. Considering the methods President Masaryk used to interfere in several internal political disputes, at least his impartiality is a myth.

René Küpper, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Selected Bibliography

- Hadler, Frank (ed.): Weg von Österreich! Das Weltkriegsexil von Masaryk und Beneš im Spiegel ihrer Briefe und Aufzeichnungen aus den Jahren 1914 bis 1918. Eine Quellensammlung, Berlin 1995: Akademie Verlag.

- Masaryk, Tomáš Garrigue: Nová Evropa. Stanovisko slovanské (The new Europe. The Slav standpoint), V Praze 1920: Nákl. G. Dubského.

- Masaryk, Tomáš Garrigue: Světová revoluce. Za války a ve válce, 1914-1918 (English edition: The making of a state. Memories and observations, 1914-1918, New York 1927.), V Praze 1925: C̆in a Orbis.

- Polák, Stanislav: T. G. Masaryk. Za ideálem a pravdou (T. G. Masaryk. In the pursuit of ideal and truth), 6 volumes, Prague 2000: Masarykův ústav AV ČR.

- Soubigou, Alain: Thomas Masaryk (avec une préface de Václav Havel), Paris 2002: Fayard.