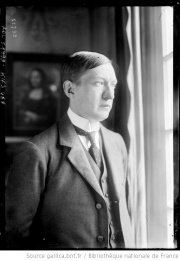

Early Life and Influences↑

Aleksandr Kerenskii (1881-1970) was born in Simbirsk, Russia, where his father was director of the Classical Gymnasium. Among the Gymnasium’s pupils was Vladimir Il’ich Ulianov (1870–1924), the future Lenin. In 1887, the execution of Ulianov’s brother for an unsuccessful plot to assassinate Aleksandr III, Emperor of Russia (1845–1894), rocked Simbirsk society. The Kerenskii family moved to Tashkent, and despite violent conflict between the local Islamic population and Russifying administrators, the young Aleksandr developed pride in Russian rule. In 1899 he departed to study law at St. Petersburg University and came under the influence of the radical student circles that included his first wife, Olga L’vovna Baranovskaia (1886–1975).

Revolutionary Activity↑

Kerenskii’s activity against the tsarist regime ignited in 1904. He distributed the liberal journal, Liberation, which demanded civil freedoms. He also opened a legal aid office for St. Petersburg’s oppressed and developed contacts with socialist sympathisers. Following Bloody Sunday on 9 January 1905, when troops fired on workers marching to petition Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1868–1918), for economic and political reform, Kerenskii visited homes of the victims on behalf of the Bar Council. He also edited a newspaper that advocated armed revolution and supported the populist Socialist Revolutionary programme. He gained renown as a lawyer defending rebellious peasants and members of national minorities, and advised survivors of the infamous Lena Massacre, the shooting of striking Siberian goldfield miners in 1912. His reputation as a spokesman against injustice spread through his speeches in the Duma, the parliament granted on a limited franchise by the Tsar in October 1905.

The Socialist Revolutionaries boycotted the parliament, but Kerenskii was elected in October 1912 to represent the peasant-based Trudovik group. Suspension of the Duma at the onset of the First World War gave Kerenskii the opportunity to revive his revolutionary agitation and join influential political, military, and industrial figures in a clandestine freemasonry organisation dedicated to ending autocracy. Kerenskii's willingness to work with socialist and non-socialist circles brought him to the fore of political life when popular demonstrations toppled the Tsar’s government in February 1917.

The Statesman↑

The vacuum left by the government’s collapse was filled by the Provisional Government of former Duma leaders; the socialist Council, or Soviet, of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies; and Kerenskii. Kerenskii greeted demonstrators and arrested tsarist ministers during the February Revolution, portrayed himself as a figure who stood above party politics, and impressed with his oratory power. All these actions and qualities coalesced in the "Kerenskii cult". Audiences threw flowers at his feet, soldiers hoisted him triumphantly aloft, and the public petitioned him with their demands. He straddled the dual power structures after the Tsar’s abdication, being elected vice-chairman of the Soviet’s Executive Committee and accepting the post of Minister of Justice in the Provisional Government, despite the Committee’s resolution to abstain from membership in the "bourgeois" government it conditionally supported. In April, a diplomatic note committing to expansionist war aims outraged the public, and unrest was only dispelled by more socialists entering into government and Kerenskii becoming Minister of War. When this coalition threatened to fall apart in July following unsuccessful military action and wrangling over agrarian and nationalities policy, Kerenskii was hailed as the man to reunite the country. He assumed the position of Prime Minister, moving into the Tsar’s Winter Palace.

Military Leadership↑

Kerenskii’s response to the war balanced patriotism with humanitarianism and dedication to revolution. When the Duma declared unity with the wartime tsarist regime in July 1914, Kerenskii called for workers and peasants to defend their country, and then rise up and liberate it. He spoke about a possible peaceful solution under democratic government. Once in power, however, he did not support peace at any price. The coalition’s policy of revolutionary defencism promised revision of war aims but ruled out separate peace with Germany and did not preclude offensive action to defend the new regime. A concerted offensive had been planned at Allied conferences starting in late 1916. In June 1917 the coalition launched the attack, believing action could strengthen Russia’s diplomatic hand, secure Allied credits, and halt the breakdown of order in the army and the country’s interior.

As Minister of War, Kerenskii toured the front, rousing soldiers to a campaign that became known as the "Kerenskii Offensive". By early July, however, advances by the 11th Army and the 8th Army, under General Lavr Georgievich Kornilov (1870–1918), turned into disorderly retreat as the Russians expended reliable troops and made tactical errors. The weather worsened. There was no coordinated Allied movement and German reinforcements arrived. Morale evaporated. In desperation, Kerenskii attempted to halt desertion and violence against civilians by reinstating the death penalty.

Historian Louise Heenan concludes that defeat was fatal for Kerenskii and the Provisional Government. Historian Marc Ferro stresses that the very decision to attack irrevocably alienated the leadership from the masses, who desired peace and suspected the offensive was an attempt to restore the power of officers and the ruling elite. Boris Isaakovich Elkin (1887-1972), an associate of Kerenskii’s political rival Pavel Nikolaevich Miliukov (1859–1943), described Kerenskii’s rallying of the troops as a rare bright moment; he contended that subsequent conflict with General Kornilov was his real failure. But it was the offensive that enhanced Kornilov’s reputation, elevated him to Supreme Commander, and galvanised his support on the right, just as it prompted an uprising from the left.

Fallen Idol↑

Under Attack↑

In July 1917, violent demonstrations erupted among garrison troops threatened with frontline duty and workers bearing Bolshevik slogans of peace and power to the Soviet. The Germans attacked Riga in August, and Kerenskii, now prime minister, discussed with General Kornilov’s political supporters the possible imposition of stricter civil controls and subordination of the Petrograd Military District to the Supreme Command. Kornilov assembled troops for an advance on Petrograd to install a rightist cabinet, but Kerenskii, having confirmed Kornilov’s intentions, ordered his dismissal. Soviet officials summoned worker and soldier detachments to impede the counterrevolutionary forces, and Kornilov was arrested. Kerenskii’s intentions during the Kornilov Affair remain disputed, in particular the extent to which he was complicit in Kornilov’s plans or sought to use Kornilov, either to create his own dictatorship or as a scapegoat for strong-arm measures, before backing down. Popular suspicion at Kerenskii’s authoritarian intentions gathered strength at the time because he limited inquiry into the events and appointed a new directory government, including members of the liberal Kadet party associated with Kornilov. He had estranged both right and left, and when the Bolsheviks marshalled an insurrection in the name of the Soviet in October, only the soldiers of the Women’s Death Batallion and some military cadets and Cossacks rallied to Kerenskii's defence.

Defeat and Exile↑

After attempts to muster loyal troops failed, Kerenskii was smuggled out of the Petrograd suburbs by the Socialist Revolutionary military organisation. He returned in secret to the capital in January 1918, when the Socialist Revolutionaries secured a majority in elections to the Constituent Assembly. By then he had been discredited by vicious criticism from the Bolsheviks and from some within the Socialist Revolutionary party. When the Assembly was forcibly closed down, Kerenskii was not given a role in the ineffectual moderate socialist resistance, but instead dispatched as an embarrassment on a diplomatic mission to London and Paris. He spent the rest of his life in exile, reflecting on the failure of his government, which he blamed on the inability to establish peace. This glossed over other shortcomings, however, such as faltering land reform, his knack for making enemies, and the Kerenskii cult that blinded him to dissatisfaction and meant he was solely blamed for governmental mistakes and military catastrophe. Ultimately, the cult turned into malicious parody.

Assessing Kerenskii↑

Assessments of Kerenskii are muddied by the distortions of the Kerenskii cult, the vitriolic machinations of Russian politics in 1917 and in emigré circles after the war, and the mythologising of the February Revolution and Provisional Government in the memoirs of participants, including Kerenskii. Definitive conclusions remain elusive about the man who went from revolutionary to occupant of the Winter Palace, from pacifist to Minister of War, from an opponent of the death penalty to a supporter of its reinstatement. Kerenskii extolled freedom but rejected autonomy for Russia’s nationalities; signed a Declaration of Soldier’s Rights but toyed with restoring order through military discipline; and was devoted to democratic government but became virtual dictator in a failed attempt to save it.

Siobhan Peeling, University of Nottingham

Section Editors: Yulia Khmelevskaya; Katja Bruisch; Olga Nikonova; Oxana Sergeevna Nagornaja

Selected Bibliography

- Abraham, Richard: Alexander Kerensky. The first love of the revolution, New York 1987: Columbia University Press.

- Elkin, Boris: The Kerensky government and its fate, in: Slavic Review 23/4, 1964, pp. 717-736, doi:10.2307/2492208.

- Ferro, Marc: The Russian soldier in 1917. Undisciplined, patriotic, and revolutionary, in: Slavic Review 30/3, 1971, pp. 483-512, doi:10.2307/2493539.

- Heenan, Louise Erwin: Russian democracy's fatal blunder. The summer offensive of 1917, New York 1987: Praeger.

- Kerensky, Aleksandr Fyodorovich: The Kerensky memoirs. Russia and history's turning point, London 1966: Cassell.