Introduction: 20th Century Context↑

Smoking and the consumption of tobacco in various forms was already a popular pastime in Europe by the outbreak of the First World War. However, whereas late-19th century smokers had enjoyed a diversity of practices and products that reflected a panoply of tastes, the advent of mass manufacturing of tobacco products fundamentally shifted the market in favour of the cigarette. Prior to this, smoking had taken a variety of forms across Europe – including the pipe and cigar – with often class-based associations of liberal individualism and leisured lifestyles. With the introduction of mechanisation, the amount of cigarettes that could be produced grew exponentially. Tobacco firms sought to create a mass demand for their product, most often through eye-catching advertising. This shift underlined an already prevalent association of smoking with modernity and the rational organisation of society by the mass market.

Mechanised production was pioneered in Britain by the tobacco firm W.D. & H.O. Wills, following their purchase of the patent for the Bonsack cigarette-making machine in 1883, which could produce up to 120,000 cigarettes per day. This innovation reduced costs for the company and lowered the price for working-class consumers. With the coming together of a number of large firms in British and international conglomerates by 1901–1902 – notably, the Imperial Tobacco Company and British American Tobacco – the dominance of the mass-produced cigarette was sealed. In Britain, by 1919 more than 50 percent of tobacco consumption was in the form of cigarettes. The export of British cigarettes globally, including Europe, cemented their ubiquity.

Smoking as a Social Practice in the Context of Total War↑

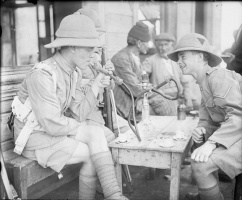

The experience of war and the mass mobilisation of both combatants and civilians created a special place for smoking and cigarettes in particular. Given that smoking was already popular, it is no surprise that – according to official estimates – over 96 percent of British soldiers were regular smokers just four months into the war. Owing to provisioning of tobacco for the Central Powers’ soldiers, those that were not smokers at the outbreak of war were generally hardened in their habit by its close. However, it was not only the pre-war rise in sales of cheap cigarettes that resulted in soldiers taking up the habit, but the social and material conditions enacted by war itself. Indeed, owing to a certain “medical ambiguity” regarding smoking among government and military authorities, cigarette consumption was actively encouraged, no less through the inclusion of cigarettes in soldiers’ ration packs. British soldiers enjoyed the largest share, amounting to two ounces of tobacco a day, while French servicemen received only twenty grams. Interestingly, German rations offered a greater variety of tobacco products, including two cigars, two cigarettes or the choice of loose tobacco or snuff. This reflected a slightly different smoking culture in Germany, where cigars were still popular and not yet totally superseded by the cigarette. Similarly, Russian soldiers initially smoked pipes in greater number, utilising the strong, cheap mahorka variety of military-issue tobacco. As the war progressed, mahorka was increasingly used to make hand-rolled cigarettes. These were easier to smoke in the confined and shifting conditions of the trenches.

The First World War also cemented tobacco production and consumption across the Central Powers, with the tobacco-producing state of Bulgaria, which entered the war in 1915, providing much of the forces’ supply of cigarettes. After entering the war in 1915, the Balkan state rapidly increased its tobacco output in order to provide the Central Powers with tobacco. Indeed, Bulgaria’s siding with the Central Powers was predicated upon a substantial Austro-German loan with Bulgarian tobacco serving as collateral. Bulgaria’s tobacco output increased from 3 to 15 million kilograms (15,000 tonnes) during the span of the conflict, with the vast majority being exported to Germany and Austria. As a result, the trade deficit in 1914 evolved into a surplus during 1915–1917. By 1917, 70 percent of Bulgaria’s exports were in the form of tobacco, up from 9.9 percent in 1909. Food shortages were the eventual result of the explosion in tobacco production and processing heralded by the war, as this adversely affected grain cultivation. As observed among the Allies, the increased popularity of the cigarette was underpinned by a widespread belief in the morale-boosting and medicinal effects of tobacco in the war context, in addition to immense economic benefits. In Bulgaria, this involved the expulsion of conglomerates such as American Tobacco from the market, leading to a state monopoly and the choking of Oriental tobacco supplies to the Allies.

Smoking was encouraged by charitable bodies on the home front seeking to provide much-needed comforts for troops fighting abroad. While some “comforts funds” raised money to send sports equipment, records, food and other everyday supplies to the front or to prisoner-of-war camps, others focussed expressly on tobacco and cigarettes. In Britain, this included the Over-seas Club Tobacco Fund, which raised over 1 million pounds to purchase tobacco and other comforts during the conflict. Each package sent by the Club included a Reply Postcard “ready-addressed to the donor, to bring back the grateful thanks of the men”, thereby seeking to draw the fighting and home fronts together. Indeed, some advertisements framed the donation of cigarettes as a patriotic act in itself. Of course, advertising also encouraged civilians to smoke cigarettes, citing similar stresses to those endured by soldiers, though related instead to air raids and lighting restrictions.

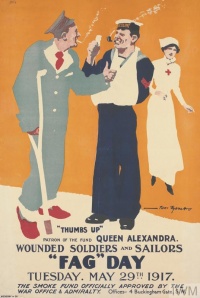

The British government organised fundraising events such as “fag days” (a play on the “flag days” common during the war), including one held in May 1917 under the auspices of the War Office and Admiralty. Many voluntary bodies such as the Red Cross Society and YMCA organised similar events during the war, including ones that raised money for the soldiers of other Allied nations. Civilians could even purchase bulk packs of cigarettes and tobacco to send to units associated with their town or city. The Tsarist regime in Russia ran similar campaigns, encouraging civilians to send tobacco to soldiers fighting at the front.

Crucially, these efforts signalled the cooperation of government and military authorities with the agents of Big Tobacco and civilian voluntary action. Implicit in this convergence of forces was a belief that the fraught and disruptive rigours of war warranted a social-psychological-medicinal solution in the form of the cigarette. According to both commercial advertising and government public information, the cigarette was the “special need”[1] of the fighting man: “Their slightest wish should be gratified, and in eighteen out of twenty cases the earnest craving of our injured fighters is for a smoke.”[2]

Health Discourses↑

Despite concerns that had circulated in Europe since the late 19th century about the moral and medical implications of smoking, during 1914–1918 the practicality and perceived social and psychological merits of cigarettes far outweighed any concerns related to health. Indeed, the principal British medical journal The Lancet proclaimed: “We may surely brush aside much prejudice against the use of tobacco when we consider what a source of comfort it is to the sailor and soldier engaged in a nerve-wracking campaign … tobacco must be a real solace and joy when he can find time for this well-earned indulgence”.[3]

While military authorities were less encouraging in their advice on tobacco use, they did not discourage it entirely. In a British military regime where soldiers were expected to maintain fitness and health, self-control was better utilised in the realm of alcohol, which was seen as potentially more damaging to “national efficiency”, given its association with sexual proclivity and indiscipline. Similar views were held by the French and Russian governments, though soldiers in particular continued to consume alcohol.

Smoking, on the other hand, was seen to calm soldiers on the battlefield, providing a means to steel resolve in advance of an attack, and an accompaniment to the relief of survival. It was also associated with codes of military masculinity and bravery, allowing soldiers to maintain an outwardly stoic attitude. However, the sense that smoking was merely a salve for the rigours of combat was offered by some contemporary representations of soldiers smoking. This included William Orpen’s (1878-1931) A Man with a Cigarette (1917), where an injured serviceman is depicted smoking in a trench. Rather than striking a heroic pose befitting the brave warrior, the smoking soldier looks gaunt, isolated and deathly.

Smoking was also associated with ideas of home and pre-war civilian life, especially among the predominantly voluntary British soldiers. Smoking a cigarette not only maintained a thread of continuity with life before the war, it also helped forge a sense of comradeship among the fighting men, and sometimes fleetingly with the enemy.

Michael Reeve, University of Hull

Section Editor: Frederik Schulze

Notes

Selected Bibliography

- Hilton, Matthew: Smoking in popular British culture, 1800-2000. Perfect pleasures, Manchester; New York 2000: Manchester University Press.

- Neuburger, Mary C.: Balkan smoke. Tobacco and the making of modern Bulgaria, Ithaca 2013: Cornell University Press.

- Reeve, Michael: Special needs, cheerful habits. Smoking and the Great War in Britain, 1914-18, in: Cultural and Social History 13/4, 2016, pp. 483-501.

- Reid, Fiona: Medicine in First World War Europe. Soldiers, medics, pacifists, London 2017: Bloomsbury Academic.