Introduction↑

The influence of the Russian revolution on the countries in East Central Europe differed considerably depending on the military situation in the area. In the Finnish, Estonian and, in part, Latvian territories behind the Russian front line, the principle of self-determination was used as a pretext for the Bolsheviks to seize power and to build a new mechanism of dependence on Russia after the October Coup. The German offensive finished the Bolshevik experiment there. Poland and Lithuania, under German occupation, were isolated from the direct impact of the revolution but still housed adherents to the revolutionary ideas.

The Kingdom of Poland↑

When the Russian revolution broke out in February/March 1917, the Kingdom of Poland had been under German and Austrian occupation for over a year and a half. The influence of revolutionary events manifested itself mainly in the change of attitude of the main political parties as well as the population towards the invaders. From the Polish point of view, the positive result of the revolution was the resonance of the Polish cause with the two competing revolutionary Russian governments: the liberal Provisional Government and the radical Petrograd Council of Workers and Soldiers Deputies. Both centers of power began appealing for Polish support, publishing two proclamations. On 27 March 1917, the Petrograd Council gave an address in which it announced that on the basis of the right of nations to political self-determination it acknowledged Poland’s claim to independence. The Provisional Government presented its stance on the Polish cause on 31 March.[1] It acknowledged the creation of an independent Polish state on the territory with a predominantly Polish population. The Provisional Government also stipulated that the state remain connected with Russia by military alliance. The constitutional character of the state as well as its territorial shape, which foresaw the unification of all three annexed Polish territories, had to be confirmed in the future by the Russian Legislative Assembly.[2] These proclamations of Russian authorities had significant meaning for Poland’s international situation.[3]

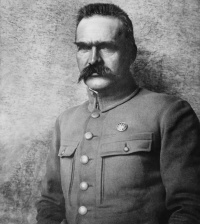

The Russian revolution weakened the Russian commitment to the First World War and strengthened the strategic position of Germany. From spring 1917, Józef Piłsudski (1867-1935) and his followers tried to change the Polish attitude towards the allied powers, believing that the threat to Polish independence from the Russian side had disappeared temporarily and that the threat from the German side had increased. Piłsudski perceived new political possibilities for the Polish nation in revolutionary Russia.[4] The Poles expressed their joy at the fall of tsarist Russia and the victory of freedom. It was clear that the resistance against the occupying powers intensified and that the number of strikes as well as of their participants rose. The radical mood, shaped under the influence of the Russian revolution were mainly caused by worsening living conditions.[5] The Polish Marxist parties which were active in the Kingdom of Poland – the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL) and the Polish Socialist Party-Left (distinct from Piłsudski’s Polish Socialist Party-Revolutionary Fraction which fought for the independence of Poland) – treated the February revolution as a forecast of the end of imperialistic war and the starting point of socialist revolution. Aspirations for independence were treated as sabotage of the socialist program and as an “anachronism” as it was time to overthrow the idea of the nation state and build an internationalist workers’ republic. This situation caused sharp conflict between the socialist parties and the supporters of an independent Polish state.

Germans and Austrians became the guarantors of the existing social order, protecting the Kingdom of Poland from the dangerous influence of the Russian revolution. In an attempt to gain Polish sympathies, the Provisional State Council (Tymczasowa Rada Stanu), set up by the German occupying power as a Polish pre-parliament in reaction to the proclamation of the Russian Provisional Government, stressed that on 5 November 1916 the Central Powers had created an independent Polish state.

The Bolshevik Council of People’s Commissars announced the Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples of Russia on 16 November 1917, which gave non-Russian nations of the former empire the right to self-determination, including the right to create independent states. As a result of the Bolshevik victory, Russia ended the war with the Central Powers and was no longer an ally of the Entente powers. The question of Poland’s independence could now be treated independently from Russian imperial policy. The echoes of the “Bolshevik revolution” reached the Kingdom of Poland. On 19 January 1918 a general strike took place in Warsaw. Among the demands was the improvement of food supply, peace and freedom for Poland. For activists of SDKPiL and PPS-Left, the Bolshevik seizure of power was understood as a signal to revolution in the Kingdom. Marxist parties, however, remained alone in their enthusiasm for Bolshevism. The majority of Polish socialists first of all wanted to build an independent state and they perceived the socialist revolution as premature.[6] For Piłsudski, who had been imprisoned in Magdeburg since August 1917, and his followers, the Bolshevik coup symbolized the demise of the Russian Empire where they hoped to establish the recruitment base for the fight against Germany and Austria-Hungary. The basic task for Piłsudski’s men was to support the development of a Polish army in Russia, in cooperation with the Bolsheviks if possible. Nevertheless, the majority of Polish soldiers desired to stop fighting, leave Russia and return to their homeland.[7]

Lithuania↑

In September 1915, the Germans occupied the larger part of the ethnically Lithuanian territories. However, since the beginning of the war, many Lithuanians had served in the Tsar’s army. For the adversaries of the German occupation, word of the Russian revolution meant hope for the victory of democracy in Lithuanian lands. On 26 March 1917 the National Lithuanian Council (Taryba) was founded by Lithuanian political parties. This political institution was essentially under German control and had only limited autonomy. The Taryba in turn convoked the Seimas (parliament) of Russian Lithuanians which met in Petrograd on 9-16 June. The Seimas disclosed deep differences between Lithuanian politicians. Nevertheless, it achieved a resolution affirming that the pre-war ethnically Lithuanian territories under Russian or German control would belong to a future Lithuanian state, the details of which would be settled at a future peace conference. For the first time a separation of Lithuania from Russia was discussed and the Lithuanian cause became an international affair. Rightist delegates advocated total independence, whereas the leftists saw the future of Lithuania in a federation with Russia.[8] The resolution of the first Russian Soviets Assembly on 20 June 1917 acknowledged the principle of decentralization of power, introduced local government and declared the right of nations to self-determination including separation from Russia with the approval of the Russian Constitutional Assembly.[9] This declaration caused a softening of the German policy towards Lithuanian aspirations of independence. On 24 September the Lithuanian Council (Lietuvos Taryba) was constituted with a majority on the right and only two Social Democrat members.

As the Taryba unanimously declared the independence of Lithuania on 16 February 1918, a new epoch in the history of Lithuanians began. The act announced the establishment of a separate, democratic state with Vilnius as the capital. On 1-3 October 1918, a small group of Bolshevik followers established the Lithuanian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) or LKP(b) in Vilnius, in total dependence on the Russian Bolsheviks. The program of the LKP(b), which had about 800 members at that time, announced the introduction of a communist system by force, the creation of an alliance with Bolshevik Russia and the establishment of a Revolutionary Provisional Government of Lithuanian Workers and Peasants. The Bolsheviks’ strategy extorted such a step in order to justify their invasion to the west. The Assembly declared the beginning of the proletarian revolution in Lithuania as its main aim but ignored the peasants.

The message about the outbreak of revolution in Germany, which reached Vilnius on 10 November 1918, had great influence on the local situation and spurred considerable political demonstrations. On 7 December 1918 the Red Army began to march to the west and reached the ethnic border of Lithuania on 12 December. The Germans withdrew, trying to avoid contact with the Bolsheviks.[10] The establishment of a communist Provisional Government of Workers and Peasants was declared on 8 December 1918 in Vilnius. The Provisional Government nominally seized power in the territory of the Lithuanian Soviet Republic and was acknowledged by Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924) in a decree on 22 December 1918. Together with the Red Army, the activists of the Provisional Government entered Lithuania. The Lithuanian government was nonetheless a puppet regime and its leadership was in the hands of Vincas Mickevičius-Kapsukas (1880-1935) who was entirely obedient to the Bolsheviks. At the end of 1918, instead of a revolution in Lithuania, military conquest by the Red Army took place. The fight against the Bolshevik invasion became the fight for Lithuania’s independence.[11]

Latvia↑

As a result of the German offensive, Latvia was divided by the front line in the autumn of 1915. Out of 1.5 million Latvians, 800,000 were evacuated to Russia voluntarily or by force. The city of Riga was transformed into a war zone. On 15 March 1917 street fights between the tsarist police and civilians, who were supported by soldiers, broke out in Riga. On 13 March the Provisional Government appointed a conservative Latvian politician, Andrejs Krastkalns (1868-1939), as a new official commissar of the Governorate of Livonia. His task was to calm the mood, which appeared to be impossible.

Riding the wave of political liberalism, active Bolsheviks under the leadership of Petris Stučka (1865-1932) profited most. The workers and peasants in the Latvian Riflemen units were under particularly strong influence of Bolshevik agitation. According to Petris Stučka, the “Latvian Rifleman was an armed worker.”[12] The biggest supporter of the Bolsheviks was the 5th Latvian Riflemen Regiment under the command of colonel Jukums Vācietis (1873-1938), later commander-in-chief of the Red Army. They quickly obtained a predominant position in the Latvian social democracy. In April 1917, during the Assembly of Workers, a radical agricultural reform proposed by the Soldiers and Peasants Delegates’ was enacted. This act introduced the confiscation of land estates from noblemen and the clergy without indemnity and their handover to the peasants. Against objections of the Provisional Government, peasant councils, which were created especially for this aim, began to operate. On 6 November 1917, the Bolsheviks conducted their revolution in Petrograd. The rebellious Latvian Riflemen supported them but part of the Russian Army in Latvia remained faithful to the government. Nevertheless, the Bolsheviks took control of railways and telegraphs. The confiscation of noble and church lands was announced.

The sharp conflict between Latvian society and the German aristocracy, as well as the fear of a German invasion helped further the revolution. The atmosphere worsened after 3 September 1917 when the Germans entered Riga. The November elections to the Russian Legislative Assembly brought the Bolsheviks a crushing victory in Latvia with 70 percent of votes. The Latvian Riflemen were sent to the front lines of the civil war and soon became a part of the Red Army. Right and center parties were declared illegal. The self-government organs qualified by the Russian Provisional Government were liquidated by the Bolsheviks. Industry, banks and railways were nationalized. On 22 February 1918 the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counterrevolution and Sabotage (abbreviated as the “Cheka,”) introduced a decree referring to the persecution of the enemies of Soviet power. Among the functionaries of the Cheka were many former Latvian Riflemen.

In response, the faction of supporters of a German invasion in Latvia asked Germany for help in the fight against Bolshevism. At the same time, the supporters of Latvian autonomy tried to gain aid from the Entente powers.[13] On 30 November 1917, during the conference of national parties in Valka, Latvia’s separation from Russia was decided. In January 1918, Latvia’s declaration of independence was made public by Jānis Goldmanis (1875-1955), a member of parliament in the Russian Constitutional Assembly. The independence movement had weak support because it suffered from internal political differences and lacked a strong leader. This situation led to political strife in Latvia but did not lead to civil war. In February 1918 German troops occupied Latvia. Article 3 of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk announced a renewed division of Latvia into the separate lands of Courland, Livonia and Latgallia, all of which had already been under German control. After their military defeat, the Bolsheviks acknowledged German rule in Latvia, despite the pro-Soviet attitude of the majority of Latvians, in order to sustain the power and safety of Petrograd. The German occupation began and the Bolshevik regime was over. As a result of German conquest it became impossible for national politicians to proclaim independence. This became possible again only after the defeat of Germany in November 1918.[14]

Estonia↑

In February 1917, the biggest revolutionary demonstrations in Estonia took place in large cities where many workers lived and tsarist garrisons were stationed. On 14 March 1917 strikes in several factories of Reval (later Tallinn) turned into a general strike in the whole city. As throughout Russia, rivalry between the Provisional Government and the soldiers’ delegates councils began. The Provisional Government dismissed the governors and the chiefs of administrative districts, replacing them with its commissars. On 17 March the Estonian governor commissar of the Provisional Government (the mayor of Reval since 1913), Jaan Poska (1866-1920), replaced the former tsarist governor Pëtr Verëvkin. The leftist revolutionaries – Mensheviks as well as Socialists – began creating workers and soldiers delegates’ councils. In Dorpat (Tartu) the assembly of deputies of Estonian organizations presented for the first time the project of Estonian autonomy. On 26 March a mass demonstration in support of autonomy was organized in Petrograd. The activity of society made great impression on the government which on 30 March introduced an administrative and self-government reform in the Estland (Estonian) Governorate. An autonomic organ of power – the Provisional National Council – was established. This Provisional Government wanted to secure the loyalty of Estonians in new Russia, permitting them to introduce national autonomy as well as freedom of political activity. Estonia became the only land of Russia whose autonomy was guaranteed by the Provisional Government.[15]

An important issue in the development of Estonian autonomy was gaining the peasantry’s support for the national cause by introducing effective agricultural reform. After the revolution, tenant farmers wanted to liquidate the vestiges of serfdom which still existed in the form of rent payment. The German aristocracy under the leadership of Eduard von Dellingshausen (1863-1939) was not in favor of this move but on 15 April 1917 the Provisional Government was able to abolish serfdom. At the same time, political changes occurred and new parties were founded. The most important leaders were Jaan Tõnisson (1868-1941) from the Estonian Democratic Party, Jüri Vilms (1889-1918) from the Estonian Socialist Radical Party, later the Labour Party and Jaan Hünerson (1882-1942) from the Estonian Peasants Union. On the left the Estonian Socialists-Revolutionaries as well as the Bolsheviks were significant, both quickly growing in strength. On 16-17 April 1917 the first Estonian Bolsheviks conference, under the guidance of the barrister Jaan Anvelt (1884-1937), took place in Tallinn. Soon after his return from exile in Russia, the leader of the Estonian Bolsheviks, Viktor Kingissepp (1888-1922), joined the party.

On 1 July 1917 in the castle of Toompea in Tallinn, the Maapäev (the Estonian Provincial Assembly) convened for the first time. It was the first Estonian legislative organ, under the leadership of future prime minister Konstantin Päts (1874-1956) from October on. Then came crucial events on the Eastern Front: on 3 September 1917, German troops entered Riga and on 12 October they occupied the islands of the Moonsund archipelago off the Estonian coast. In the situation of growing chaos, Bolshevik propaganda effectively influenced the agricultural proletariat and soldiers. The Bolshevik party formed its own armed squads: the Red Guard. Preparing to stage a coup, the Bolsheviks counted on the support of a gigantic Russian garrison in Estonia which in autumn 1917 had 200,000 men. After the alleged coup of General Lavr Kornilov (1870-1918) the Bolsheviks could represent themselves as defenders of the revolution and as suppliers of arms to the Tallinn garrison. Thanks to energetic action the Bolsheviks quickly took control over transport and communications. On 8 November 1917 the power in Estonia passed to them without bloodshed.

Estonian society did not defend the Provisional Government which, after the military defeats, seemed clumsy and fear of a German attack circulated, On 9 November 1917 Jaan Poska handed over power to the deputy of the Revolutionary Committee, Viktor Kingissepp. The Executive Committee of the Councils of the Estonian Delegates under the leadership of Jaan Anvelt held executive power. Communal and municipal councils of delegates were chosen in democratically but only workers, craftsmen and poor peasants were allowed to take part in the elections. The Estonian language became the official language of instruction in schools. The Bolsheviks appointed revolutionary Courts of Justice which had to be chosen by the voting population. Working class committees stopped the export of factory machines to Russia and took control of private factories, railways and banks. Private property no longer existed. Following the Russian example, state farms (Sovkhoz) were created. This caused dissatisfaction among the peasants who waited in vain for a land assignment. Resistance from owners was crushed by squads of the Red Guard. Bolshevik propaganda claimed that “national consciousness” was disappearing. Therefore, the Estonian national identity was ignored and the councils of delegates were populated by Russian soldiers. In the elections to the Estonian Constituent Assembly in November of 1917 the Bolsheviks received only 39 percent of the votes, mainly thanks to the soldiers’ support.

A strong anti-Bolshevik front formed. In this context, national parties changed their attitude towards the Germans, seeing in them the strength necessary to hold Bolsheviks back. On 25 February 1918, the Germans occupied Tallinn, ending the epoch of 200 years of the Russian rule. All Bolshevik officials fled to Russia. In a few clashes with the Red Guard, Estonian soldiers and members of a local militia, Omakaitse, supported the Germans. Anti-Bolshevik uprisings emerged in Tallinn, Tartu, Rakvere and other cities. For the first time the obvious aim for all oppositionists was the independence of the state. Autonomy became the new Bolshevik slogan.[16]

On 19 February 1918, the highest power in the state was taken over by the Estonian Committee of Rescue under the leadership of Konstantin Päts and Jüri Vilms, who announced Estonia’s neutrality in the German-Bolshevik war. On 24 February in Tallinn the independence of Estonia was proclaimed. Päts became Prime Minister, Vilms his deputy. However, all acts and activities for Estonian independence were invalidated by German military authorities. Article 6 of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk obliged Russians and Germans (nominally) to withdraw their armies from Estonia. Russia, however, still treated Estonia as an integral part of its territory but the Bolshevik power in Estonia could have been rebuilt only by conquest from outside. Soviet Russia was not ready for this action until the end of 1918.[17]

Finland↑

On 16 March 1917, the sailors’ revolt on the ships of the Baltic Fleet began in reaction to the outbreak of the February Revolution in Helsinki. The Finns observed the events carefully, believing that the changes in Russia would bring them freedom. The February Revolution had an important influence on the radicalization of main Finnish parties – the Social Democratic Party, the Finnish Party and the Young Finnish Party. The Finnish senate in April 1917 became the first government in the world with a majority of socialists.[18] On 3 July 1917 the Social Democrats won a majority in parliament (Eduskunta) with a crushing victory in elections. The parliament became the highest power (previously belonging to the Russian tsar) but decisions regarding foreign policy, military issues and the appointing of the new government were still in made by the Russian government.

The leader of the Social Democrats, Otto Wilhelm Kuusinen (1881-1964), planned to carry out radical social reforms in Finland. In order to stop the strengthening of the Finnish parliament, the Provisional Government dissolved it and set new elections for October. This time the Social Democrats lost their position to the middle class parties. These parties aspired to the final separation of Finland from Russia. The Social Democrats also acted to gain independence but in close cooperation with the Bolsheviks. On 15 November 1917, the parliament announced that it would temporarily take over full power. It resolved the introduction of the eight-hour working day and reformed the self-government electoral right, i.e. the right for Finns to control their parliament. This caused the resistance from the ruling middle class parties which formed a strong block against influential opposition of Social Democrats. On 14 November the Finnish Trade Union went on strike in support of the Social Democrats. In violent riots in Helsinki twenty two people lost their lives.[19] During the strike the parliament appointed the new government of Pehr Evind Svinhufvud (1861-1944) who in March had returned from Russian exile. In his government there was no place for the Social Democrats. The most important issue for Svinhufvud was the declaration of independence of Finland as a free republic on 6 December 1917, which became his great success. However, Svinhufvud’s efforts to have western European countries acknowledge Finland was a failure. On Lenin’s order, the Council of People’s Commissars acknowledged the independence of Finland on 4 January 1918. After this event France and Germany also proclaimed their acknowledgement of the new state.

The costs of the First World War ruined the Finnish economy which was based on agriculture. A wave of powerful strikes swept the country in response. At the beginning of 1918, 42,000 Russian soldiers were stationed in Finland. Their withdrawal was delayed by the Bolsheviks. At that time the Finnish Red Guard formations already had 30,000 men. On 16 January 1918 the former Russian general, Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim (1867-1951) became commander of the White forces (called the civil guard).[20] On 12 January the parliament gave Svinhufvud special plenipotentiary power for the maintenance of order.

Instead of a social revolution, a civil war broke out in Finland. On 28 January 1918 the Revolutionary Government (called the People’s Delegation) came into being with Kullervo Manner (1880-1939) as its leader.The war began with the disarmament of a few Russian garrisons. The majority of the Russian soldiers did not want to take part in a Finnish war and willingly allowed themselves to be disarmed, aiming only to return to Russia. The representatives of the People’s Delegation wanted to introduce radical social reforms but only after the establishment of a socialist regime, which never came into existence. In the few months of the civil war, 30,000 people lost their lives; in this number the losses of the Bolsheviks predominated. On 3 April 1918 the German Expeditionary Corps under the command of General Rüdiger von der Goltz (1865-1946) landed on the Finnish coast. Unbeknownst to General Mannerheim, Prime Minister Svinhufvud had traveled to Germany earlier in hopes of gaining German support. The success of Mannerheim’s offensive and the occupation of Helsinki by the Germans on 13 April 1918 brought the Whites the decisive victory. The civil war had a deep impact on Finnish society. For the next forty years, Finnish trade unionists and worker activists who were in Finland during the war were accused of betrayal and Bolshevik sympathies.[21]

Conclusion↑

The Russian revolution created the possibility of gaining more freedom within the structure of the Russian state for East Central European nations, autonomy at first, followed by full independence. The Bolsheviks did not accept the separation from Russia of the former western governorates. After the stabilization of the regime in Russia and the German retreat, the Bolsheviks tried to conquer these lands using revolutionary ideas as a propaganda tool. In the case of the Baltic states, the Bolshevik expansion succeeded for the short time but this was a military invasion from the outside without greater local support.

Paweł Brudek, German Historical Institute Warsaw

Section Editors: Ruth Leiserowitz; Theodore Weeks

Notes

- ↑ Holzer, Jerzy/Molenda, Jan: Polska w pierwszej wojnie światowej [Poland during the First World War], Warsaw 1973, p. 275.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 276; Tanty, Mieczysław: Rewolucja rosyjska a sprawa polska 1917–1918. [Russian Revolution and Polish question 1917-1918], Warsaw 1987, p. 99; Nowak, Andrzej: Polska i trzy Rosje. Studium polityki wschodniej Józefa Piłsudskiego (do kwietnia 1920 roku), [Poland and three Russias. The Study of Józef Piłsudski's eastern policy (to April 1920)], Cracow 2008, pp. 29-30; Pajewski, Janusz: Odbudowa państwa polskiego 1914–1918 [The reconstruction of the Polish state 1914-1918], Poznań 2005, p. 137.

- ↑ Bear in mind that for the Entente powers – England and France – the Polish cause after the Russian revolution was only an internal affair of Russia.

- ↑ Tanty, Rewolucja 1987, p. 119; Holzer/Molenda, Polska 1973, p. 279; Nowak, Polska 2008, pp. 31-32.

- ↑ Holzer/Molenda, Polska 1973, pp. 282, 285-288; Pajewski, Odbudowa 2005, p. 141.

- ↑ Holzer/Molenda, Polska 1973, pp. 339, 343, 353, 355-356; Pajewski, Odbudowa 2005, pp. 194, 201.

- ↑ Nowak, Polska 2008, pp. 51-54.

- ↑ Kiaupa, Zigmantas: The History of Lithuania, Vilnius 2002, pp. 312-314; Ochmański, Jerzy: Historia Litwy [History of Lithuania], vol. III, Wrocław et al. 1990, p. 266; Łossowski, Piotr: Litwa, Warsaw 2001, p. 56.

- ↑ Nowak, Polska 2008, p. 30.

- ↑ Kasperavičius, Algis: Rok 1918 w litewskiej historiografii radzieckiej i współczesnej [The year 1918 in Soviet-Lithuanian and contemporary Lithuanian historiography], in: Grinberg, Daniel/Snopko, Jan/Zackiewicz, Grzegorz (eds.): Rok 1918 w Europie środkowo-wschodniej [The year 1918 in the Central-East Europe], Białystok 2010, pp. 234-235; Ochmański, Jerzy: Historia Litwy [History of Lithuania], Wrocław 1990, p. 277; Kiaupa, Zigmantas: The History of Lithuania, Vilnius 2002, pp. 325–326.

- ↑ Ochmański, Historia 1990, pp. 273, 278–279; Kasperavičius, Rok 1918 2010, p. 235; Kiaupa, History 2002, p. 327.

- ↑ Paluszyński, Tomasz: Walka o niepodległość Łotwy 1914–1921 [The fight for Latvia's independence 1914-1921], Warsaw 1999, p. 59.

- ↑ Paluszyński, Tomasz: Walka o niepodległość Łotwy 1914–1921 [The fight for Latvia's independence 1914 - 1921], Warsaw 1999, pp. 61-62, 75-78; Lieven, Anatol: The Baltic Revolution. Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and the Path to Independence, New Haven et al. 1993 p. 58.

- ↑ Paluszyński, Walka 1999, pp. 79-81, 87, 89; Jēkabsons Ēriks: Rok 1918 na Łotwie. Okupacja niemiecka i tendencje niepodległościowe [The year 1918 in Latvia. The German occupation and independence tendencies], in: Grinberg/Snopko/Zackiewicz (eds.), Rok 1918 na Łotwie 2010, pp. 34-36.

- ↑ Raun, Toivo U.: Estonia and the Estonians, Stanford 1987, p. 95; Paluszyński, Tomasz:Walka o niepodległość Estonii 1914–1920 [The fight for Estonian independence 1914 – 1920], Poznań 2007, pp. 71-73, 75; Clemens, Walter C. Jr.: Baltic Independence and Russian Empire, New York 1991, p. 31.

- ↑ Paluszyński, Walka 2007, pp.136, 140, 144-146, 149, 151, 154, 160, 170; Lewandowski, Jan: "Wybijanie się na niepodległość" w roku 1918 w Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej [“Gaining the independence” in the year 1918 in the Central-East Europe], in: Grinberg/Snopko/Zackiewicz (eds.), Rok 1918 2010, p. 22; Clemens, Baltic Independence 1991, p. 31.

- ↑ Paluszyński, Walka 2007, pp.171-176, 179; Lewandowski, Estonia 2001, pp. 61-63, 65-66, 68; Raun, Estonia 1987, p. 107.

- ↑ Paluszyński, Walka 2007, p. 65; Jussila, Osmo/Hentilä, Seppo/Nevakivi, Jukka: Historia polityczna Finlandii 1809–1999 przeł [The Political History of Finland 1809-1999], Cracow 2001, pp. 103-105.

- ↑ Cieślak, Tadeusz: Historia Finlandii, Wrocław et al. 1983, pp. 209-212; Jussila/Hentilä/Nevakivi, Historia 2001, pp. 112-113.

- ↑ Jussila/Hentilä/Nevakivi, Historia 2001, pp. 114-116, 118-119; Cieślak, Historia 1983, pp. 214-216; Mannerheim, Carl Gustaf: Wspomnienia [Memoirs], przekład Krystyny Szelągowskiej, wstęp i przypisy Michał Kopczyński, [translated by Krystyna Szelągowska, introduction and references by Michał Kopczyński] Warsaw 1996, pp. 85-86.

- ↑ Jussila/Hentilä/Nevakivi, Historia 2001, pp. 121-124, 129, 133; Cieślak, Historia 1983, pp. 218-221; Mannerheim, Wspomnienia 1996, p. 112.

Selected Bibliography

- Balkelis, Tomas: The making of modern Lithuania, London; New York 2009: Routledge.

- Clemens, Walter C.: Baltic independence and Russian empire, New York 1991: St. Martin's Press.

- Grinberg, Daniel / Snopko, Jan / Zackiewicz, Grzegorz (eds.): Rok 1918 w Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej (The year 1918 in East-Central Europe), Białystok 2010: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku.

- Grinberg, Daniel / Snopko, Jan / Zackiewicz, Grzegorz (eds.): Lata Wielkiej Wojny. Dojrzewanie do niepodległości, 1914-1918 (The years of the Great War. Reaching independence, 1914-1918), Białystok 2007: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku.

- Holzer, Jerzy / Molenda, Jan: Polska w pierwszej wojnie światowej (Poland during the First World War), Warsaw 1973: Wiedza Powszechna.

- Jussila, Osmo / Hentilä, Seppo / Nevakivi, Jukka: Historia polityczna Finlandii, 1809-1999 (The political history of Finland, 1809-1999), Krakow 2001: TAiWPN Universitas.

- Kiaupa, Zigmantas: The history of Lithuania, Vilnius 2002: Baltos lankos.

- Lieven, Anatol: The Baltic revolution. Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and the path to independence, New Haven 1993: Yale University Press.

- Nowak, Andrzej: Polska i trzy Rosje. Studium polityki wschodniej Józefa Piłsudskiego, do kwietnia 1920 roku (Poland and three Russias. The study of Józef Piłsudski's eastern policy, to April 1920), Krakow; Warsaw 2001: Wydawn, ARCANA; Instytut Historii PAN w Warszawie.

- Paluszyński, Tomasz: Walka o niepodległość Łotwy 1914-1921 (The fight for Latvia's independence 1914-1921), Warsaw 1999: Bellona.

- Paluszyński, Tomasz: Walka o niepodległość Estonii, 1914-1920 (The fight for Estonian independence, 1914-1920), Poznań 2007: Wyższa Szkoła Języków Obcych.

- Raun, Toivo U.: Estonia and the Estonians, Stanford 2001: Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University.