Introduction↑

Belgium suffered considerable economic losses during the war, much of which had been fought on Belgian territory. Aside from the direct damages, which were the result of warfare (the destruction of buildings, transport infrastructure or land for agriculture), Belgian industry had another competitive handicap. This handicap was a consequence of losing export opportunities following the blockade, the stoppage of economic activities that were not directly useful to the German war effort, and the dismantling of its industrial infrastructure. Moreover, a large part of the population had been forced into unemployment. Belgium had to pay for the occupation costs, leading to monetary expansion, fuelled also by the introduction of German marks as means of payment.

Post-war governments had to find a way to handle these complications. Financial problems raised most issues, since reconstruction was begun in 1918 on the supposition that Germany would pay for the war damages. As this proved not to be the case, the financial burden that had led to monetary instability was only solved in 1926. Reconstruction could not be based on principles of 19th century economic liberalism; inflation turned out to be a persistent phenomenon; and as a consequence of the post-war social and political democratization, a social policy with a limitation of market forces became part of the economic policy. Taxation was made more redistributive, and the positions between social groups shifted.

Research on post-war economic and financial reconstruction after the First World War in Belgium goes back to 1926, when the Institut de Sociologie at Brussels University published a book that offered a variety of perspectives on reconstruction, including industry, agriculture and finance, written by economists as well as sociologists.[1] Since then, the economic and financial reconstruction has not been subject of specific research. Post-war reconstruction was part of the research on the history of banking (Société Générale, National Bank),[2] and it was a central topic for long-term research on fiscal policy, since the time following the First World War was a period marked by many changes in the taxation system.[3] Post-war economic and financial change was also analysed in the scope of studies of the interwar period, particularly ones dealing with economic history and the history of prices and wages.[4] Two specific topics relevant to post-war economic and financial reconstruction were studied in depth during the 1970s and 1980s, namely the question of the German reparation payments,[5] and the Poullet-Vandervelde government (1926).[6] This left-wing government tried to stabilize the monetary system, hoping to put an end to the financial problems that originated in the war. They did not succeed, however, and instead had to give way to a government of national unity, in which representatives of the private banking sector held key positions in handling monetary matters. During the process of post-war financial and economic reconstruction, the big private banks repositioned themselves in Belgium’s economic and political system.

This article begins with a short overview of the war damages, before analysing the economic reconstruction and the policy choices that were made. The focus then shifts onto the financial and monetary consequences of this policy, and the way that those issues were handled. Special attention will be paid to the role of the banking sector, the political dimensions of the reconstruction, and its social effects at macro-level.

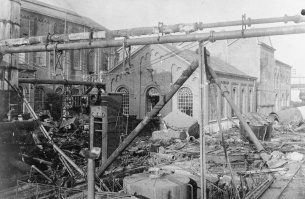

War Damages↑

Before the First World War, Belgium was an important industrial power. Its industry, based on coal, steel, engineering, textiles and glass, was export-oriented and dominated by the big banks, e.g. Société Générale. Since the late 19th century, Belgian financial groups invested in foreign countries like Russia, China and the colony of Congo, mainly in transport infrastructure.

War and occupation had serious repercussions for the Belgian industry, which was no longer able to export industrial products and import raw materials following the blockade. Industry was part of an occupied economy, implying that the Germans largely decided what type of economic activity could be maintained. They prioritized the sectors useful for themselves, explaining the continuity of coal production.[7] This was the exception, however, as is shown by the index of industrial production.[8]

| Year | Belgian index (for industrial production) |

| 1913 | 100 |

| 1914 | 64 |

| 1915 | 37 |

| 1916 | 36 |

| 1917 | 30 |

| 1918 | 29 |

Table 1: Belgian index (for industrial production), 1913-1918[9]

Industrial production fell even more as a consequence of the German policy to dismantle parts of the Belgian industrial infrastructures from 1917 onwards. Key materials for war production like copper were simply taken from machines, making production impossible. The metal industry was severely affected. The steel industry, one of the economic key sectors, serves as poignant example to illustrate the loss of production activity. In 1915-1916, only six of the fifty-four blast furnaces were working; in 1917, only one was in production; and by 1918, all blast furnaces had been blown out.[10] The limited industrial production caused mass unemployment. The unemployed, a number of which were deported to Germany from 1916 onwards, were supported by the Comité National de Secours et d’Alimentation (Committee for Aid and Food). This Committee was an initiative of the economic and financial elite, which also organized the import of food to Belgium from overseas.[11]

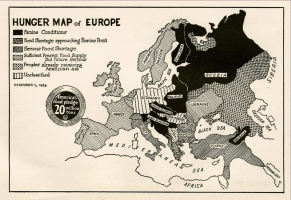

Food was scarce during the war. Before the First World War, Belgium already needed to import food, and part of the country’s agricultural area could not be used since it was in the war zone. As a consequence, agriculture became very profitable, especially on the black market, resulting in an increase of wealth in the countryside.[12]

The total war damage was estimated at 36 billion Belgian francs (expressed in the cost of reconstruction in Belgian francs – i.e. the investment needed in Belgian francs when the report was made in 1921):

| Sector | Cost of Reconstruction in Belgian francs (billion) |

| Industry | 8,3 |

| Agriculture | 2,0 |

| Transport | 5,8 |

| Property of the state, provincial and local authorities and private persons | 12 |

| Other | 7,9 |

Table 2: Cost of Reconstruction in Belgian Francs (billion)[13]

The monetary system was severely disorganized and affected by war inflation. From December 1914 onwards, the National Bank could no longer issue banknotes because the printing material was in London and the exile government prohibited the transfer to Belgium. The Société Générale took over this role. Aside from Belgian money (banknotes of the National Bank and of the Société Générale), German marks were used as currency in Belgium. Following Gresham’s law, Belgian bank notes were saved and had disappeared from circulation by 1916. Germans imposed occupation costs on Belgium. Initially, they requested 40 million francs per month, by May 1917 the amount had increased to 60 million francs per month. The total sum paid throughout the war amounted to 2.280 million Belgian francs. The costs were paid by the provinces which issued special interprovincial bonds, taken by the issuing institute, private banks and the public.[14] Monetary circulation increased dramatically under occupation. Prices had risen sharply, especially for food sold on the black market, as shown in the Brussels price index calculated by Peter Scholliers. In general, Belgian prices were four times higher in 1918 than in 1913.[15]

| Year | Belgian Price index for food |

| 1914 | 100 |

| 1915 | 128 |

| 1916 | 189 |

| 1917 | 343 |

| 1918 | 534 |

| 1919 | 497 |

Table 3: Brussels price index for food, 1914-1919[16]

Foundations of the Post-War Economic and Financial Reconstruction↑

Post-war economic reconstruction had to deal with two basic problems. It had to manage the reconstruction of the “real” economy (especially industry and transport), and it had to handle finance. Politics played a key role in this process. The Belgian policymakers thought that Germany was obliged to and would pay reparation costs. The consequences of this assessment were that state loans were more easily contracted at the capital market, and the Belgian nation (thus the state) was responsible for the reparation of all war damages. Individuals were paid by the state, which would, in turn, claim the money from Germany.[17] Reconstruction could thus be begun immediately after the war, as it would be financed by the state. The state budget, however, showed persistent high deficits, and so public debt rose rapidly, as shown in table 4.

| Year | Public debt in Belgium (in million Belgian francs) |

| 1919 | 25.500 |

| 1920 | 31.000 |

| 1921 | 37.000 |

| 1922 | 39.500 |

| 1923 | 40.500 |

| 1924 | 40.700 |

| 1925 | 41.700 |

Table 4: Evolution of public debt in Belgium, 1919-1925[18]

The second political factor that had an impact on reconstruction was the political and social democratization which occurred between 1918 and 1922. In 1919, universal male suffrage was introduced, which gave the labor movement real political power. In turn, they used their influence to introduce new social laws.[19]

Economic reconstruction was declared complete by 1924. Belgian industry had reached its pre-war level of production, and destroyed buildings as well as the transport infrastructure had been rebuilt. The reconstruction occurred on a pre-war basis and efforts for renewal were not entirely successful as was the case with a plan from the banks to concentrate Belgian steel production in order to improve the competitive position of the sector. While the Belgian industry came to a standstill, the belligerent countries had developed their heavy industry and neutral countries such as the Netherlands emerged as new competitors.[20]

Reconstruction of the Belgian economy advanced rapidly because the state was prepared to contract debts in Belgium and abroad, creating relative financial abundance. The cost was kept out of the normal budget, and transferred to special accounts instead. A new public financial institution, the Société Nationale de Credit à l’Industrie (SNCI), was created to fund industrial reconstruction.[21] Some of the new social laws (e.g. on unemployment insurance) created extra expenses for the state. When the new fiscal system was introduced, it was met with opposition and took time to generate financial effects.[22] The state deficit grew, and as it became clear that reparations would not be paid by Germany after all, it became a real and persistent problem.

Inflation also proved to be a lasting phenomenon, contrary to many financial experts’, as well as the National Bank’s expectations.[23] One of the main reasons for the monetary problems was the decision to change the Marks in Belgian francs at the 1914-rate of 1.25 Belgian francs for one Mark, while the current market rate was only half.[24] This decision was made in accordance with a concept of national solidarity, prevalent in the execution of post-war reconstruction. According to this idea, citizens should not have to pay for the war damage, but rather that this was a matter of national solidarity and that the state should claim the money directly from Germany. The difference between the exchange rate offered and the market rate was considerable and would have created monetary problems in itself. Moreover, a mass of Marks owned by non-Belgian citizens was brought to Belgium for exchange. An assessment of all the aforementioned factors explains the instability of the Belgian franc.

Belgium’s monetary instability was not only a macro-economic problem, but also had social effects.[25] Social groups that relied on small savings, rents and fixed incomes were not directly protected from inflation and confronted with a decrease in real income. While the middle-class in Belgium had fared rather well before the war, their social position was now in relative decline. Industry, however, profited from inflation.

Before 1914, Belgium was a country of low wages, and social insurance policies were not well-developed. After the war, the demand for labor was high and workers were in a position to improve their social position. Next to higher wages, which were partly the result of a post-war strike wave, wage formation became institutionalized and the unions acquired the monopoly of workers’ representation. In the key sectors of the economy, joint commissions with equal representation of unions and employers were introduced. The commissions determined minimum wages for an entire sector, and wages were linked to the retail price index. These mechanisms were laid down in collective labor agreements, which became more common in companies and sectors without a joint commission, too. The index offered a certain degree of protection against inflation.

Social legislation was improved after 1918. In 1921, the eight-hour working day (forty-eight hours per week) became the legal norm; the unemployment insurance organized by the unions was subsidized by the state in 1920; and a pension insurance scheme was in place by 1924. Unions were able to better their legal and political position. Union freedom was recognized in 1921, and the legal impediments on striking in the penal law were dropped. The changed system of institutionalized wage formation limited the market’s impact on wages. This new structure was one of the signs that the pre-war liberal order had come to an end, and that post-war economic reconstruction could no longer be based on pre-war liberal principles.

The third contributing factor to the improvement of the workers’ situation was the reform of the taxation system. Until 1914, it had been organized according to liberal principles and had entailed no redistribution of income. A tax on war profits, a reform of the right of inheritance (e.g. moveable property would also be taxed), and a slightly more progressive income tax laid the foundations for a more redistributive taxation system.[26]

A major change was the ‘national turn’ of Belgian capitalism after the First World War. After the Russian Revolution and the social and political upheaval in other parts of Eastern Europe, those regions no longer offered promising investment perspectives for the Belgian banks. Belgian financial groups, such as the Société Générale or the Banque de Bruxelles, concentrated on their own country’s manufactory. The Société Générale had doubled its nominal capital in order to finance the reconstruction of Belgian industry. A new system of portfolio investment made it possible to control companies with a limited input in capital. Next to investments, further efforts were made to gain direct control of firms. Bank directors became directly and actively involved in the management of industrial companies in which the banks had invested.[27]

Banks changed their organization to collect more deposits, which in turn could be invested in Belgian industry. Before the war, banking was concentrated in Brussels. Since there had been an increase in income and wealth in the countryside, banks from the capital spread their activities to the provinces. The Société Générale started a system to patronage regional banks, increasing the number of branches from sixty-one before the war to 350. Its contender, the Banque de Bruxelles which had been present only in Brussels before the war, now counted twenty-one branches.[28] The expansion of the big private banks’ activities brought them in competition with the National Bank, which also gave credits to the industry. The new Société Nationale de Crédit à l’Industrie was closely linked with the National Bank and yet another rival for the private banks.

The financial groups encouraged concentration and integration of production, as well as modernization and specialization in certain sectors including chemicals and textiles.[29] Nevertheless, the Belgian industry remained primarily based on production of semi-finished products that had a low added value for the world market. The colony of Congo still offered investment opportunities that complemented the Belgian economy (e.g. non-ferrous industries).

The ‘national turn’ of the financial elite was also noticeable in politics. Emile Francqui (1863-1935), a director and vice-governor of the Société Générale from 1923 onwards, deemed it reasonable to accept universal male suffrage, which was the Socialist Party’s central demand. The financial group was nothing but an outsider in the political process which adhered to a different set of rules after the war than it had before 1914. Coalition governments had become necessary, and Socialists participated in the national coalition governments (Catholic, liberal, Socialist) which laid the foundation for economic reconstruction. Henri Jaspar (1870-1939), one of the key politicians in post-war politics, was a confidant of the Société Générale. The political involvement of the private financial elite was connected to the complexity of the financial and economic questions posed by post-war reconstruction. Bankers, rather than politicians, had the required expertise.[30]

Their involvement in politics was openly discussed in the field of public finance. Since the budget was in deficit, the state had to make an appeal to the (foreign) capital markets, giving the private banks a key position. There was the consortium of private banks for the Belgian financial market with which internal loans could be placed. For foreign loans, the private banks acted as intermediaries. Emile Francqui participated in the peace negotiations, negotiations on reparations, and on the exchange of the Mark. He was foreign member of the Reichsbank, a position that was held by a representative of the National Bank in other countries. In Belgium, it was not the National Bank but private banks which took the lead of financial reconstruction: the National Bank was weaker than the private banks, which can be explained by the integration of the big private banks in international financial networks and the key role of the Société Générale in the monetary field during the war.[31] The weakness of the public sector as compared to the private sector also shows in the way that the inventory of the industry’s war damages was established. While in other countries, state institutions were in charge, in Belgium it was the central trade organization Comité Central Industriel that made the inventory and used it for the negotiations on the reparation of war damages.[32]

The 1926 Financial Reconstruction↑

The key role of the big private banks became apparent with the financial heritage’s liquidation of post-war reconstruction. By 1925, Belgium’s financial and monetary situation had become critical. The Ruhr-occupation by Belgium and France was not a success and had a negative effect on the Belgian economy. The exchange rate of the Belgian franc remained low and unstable. Aside from the fact that it had become clear that Germany would not pay all its war damages, the United States was not prepared to acquit the war loans, as had been expected initially. Moreover, the French franc, closely associated with the Belgian franc for the general public, was weakened too, while a loan came at the expiry date. The debt of the state was at its highest and much of it was floating debt, which was a factor of budgetary instability. The state was in debt with the National Bank, too, a consequence of the way the reimbursement of the exchange of the Deutschmark had been organized.

It was in this context that Albert-Edouard Janssen (1883-1966), director of the National Bank, was made minister of finance under a left-wing government (consisting of Socialists, who had won the election and were the largest group in Parliament, alongside Flemish Christian Democrats). Janssen’s plan to cope with monetary instability included achieving an equilibrium of the state budget by cutting expenses, and a tax reform at the disadvantage of the higher income groups. The debt of the state to the National Bank was to be paid back with an international loan and through a revaluation of the gold stock of the Bank. The aim was stabilization at 106-107 Belgian francs for one British pound, which would more or less be a return to the pre-war gold standard. This approach reflected the monetary orthodoxy of the National Bank, which was convinced that a return to the pre-war liberal monetary order was actually possible. The plan ultimately failed because of an organized (press) campaign by the right wing opposition, and the private banks’ less cooperative attitude, led by the Société Générale.[33] The government fell and Francqui became minister in the new national cabinet, and the main policymaker of the financial reconstruction. His plan implied strict control of the state expenses and a consolidation of the floating debt by a forced exchange for shares of the newly established railway company, the exploitation of which was to be organized following industrial principles. Francqui used this plan to impose reform of the National Bank. The governor of the National Bank was replaced by a confidant of the private banks, and representatives of the industrial sectors became directly involved in the management of the bank, which now had to limit its activities to the field of industrial credit. The ties with the SNCI were severed. The relation between the public sector and the private banks, especially the Société Générale was redesigned to the big banks’ advantage. The hostility of the Société Générale against Janssen’s plan of 1926 was not only inspired by its rivalry with the National Bank, but was connected with the economic consequences of the solution proposed by Janssen. The exchange rate of 106-107 Belgian francs per British pound would lead to a severe deflation with negative effects on Belgian industry, while the financial groups’ priority was now with industrial expansion.[34] After it had stabilized, the Société Générale continued on with industrial expansion, branching out to new sectors including electricity and favoring concentration, helped by a change in legislation (1927) to facilitate mergers.[35]

Limiting the impact of the indexation mechanism of wages by the employers offered only a limited protection of purchase power against inflation. Consequently, the new financial institutional configuration of the post-war period was not a fundamental threat to the interests of the financial elite, which is a possible explanation as to why the competitive strategy of the Belgian industry (low prices and wages) did not change in a fundamental way after 1918.

Dirk Luyten, Centre for Historical Research and Documentation on War and Contemporary Society and University of Ghent

Section Editor: Benoît Majerus

Notes

- ↑ Mahaim, Ernest (ed.): La Belgique Restaurée. Etude Sociologique, Brussels 1926.

- ↑ Van der Wee, Herman/Tavernier, Karel: La Banque Nationale de Belgique et l’Histoire Monétaire entre les Deux Guerres Mondiales, Brussels 1975; Kurgan-Van Henternryk, Ginette: De Société Générale van 1850 tot 1934, in: Van der Wee, Herman (ed.): De Generale Bank, 1822-1997, Tielt 1997, pp. 69-203.

- ↑ Hardewyn, André: Tussen Sociale Rechtvaardigheid en Economische Efficiëntie. Een Halve Eeuw Fiscaal Beleid in België (1914-1962) [Between social justice and economic efficiency: half a century of fiscal policy in Belgium (1914-1962)], Brussels 2003.

- ↑ Hogg, Robin: Structural Rigidities and Policy Inertia in Interwar Belgium, Brussels 1986; Scholliers, Peter: Loonindexering en Sociale Vrede. Koopkracht en Klassenstrijd Tijdens het Interbellum in België [Wage index and social peace. Purchase power and class struggle in Belgium in the interwar period], Brussels 1985. In 1946, Fernand Baudhuin published the following book on the economic history of the interwar period: Histoire Economique de la Belgique 1914-1939, Brussels 1946.

- ↑ Depoortere, Rolande: L’Evaluation des Dommages Subis par l’Iindustrie Belge au Cours de la Première Guerre Mondiale, in: Revue Belge de Philologie et d’Histoire LXVII (1989), pp. 748-769.

- ↑ Vanthemsche, Guy: De van de Regering Poullet-Vandervelde een "Samenzwering der Bankiers"? [The fall of the Poullet Vanderverlde: a ‘conspiracy of the bankers’?], in: Revue Belge d’Histoire Contemporaine IX (1978), pp. 165-211.

- ↑ Veraghtert, Karel: De Industriële Ontwikkeling (1914-1947) [The Industrial Development], in: De Industrie in België. Twee Euwen Ontwikkeling, 1780-1980, Brussels 1981, pp. 145-188.

- ↑ Scholliers Peter, ‘Koopkracht en indexkoppeling: de Brusselse levensstandaard tijdens en na de Eerste Wereldoorlog’ [Purchasing power index: Brussels' standard of living during and after the First World War], in : Revue belge d’histoire contemporaine, IX, 1978, p. 333-382; p. 335.

- ↑ Scholliers, Koopkracht en Indexkoppeling [Purchasing power index], p. 335.

- ↑ Veraghtert, De Industriële Ontwikkeling [The Industrial Development] 1981, p. 148.

- ↑ Scholliers, Peter: The Policy of Survival: Food, the State and Social Relations in Belgium, 1914-1921, in: Burnett, John / Oddy, Derek J. (eds.): The Origins and Development of Food Policies in Europe, London/New York 1994, pp. 39-53.

- ↑ Chlepner, B.S.: Les Finances, la Monnaie et le Marché Financier, in: Mahaim La Belgique Restaurée 1926, p. 503; Mahaim, Ernest: La Fortune et le Bien Etre, in: Ibid., pp. 505-611; pp. 570-571.

- ↑ Depoortere, L’Evaluation 1989, p. 765.

- ↑ See the article on finance in Belgium during the war in this encyclopaedia.

- ↑ Scholliers, Loonindexering en Sociale Vrede [Wage index and social peace] 1985, p. 299.

- ↑ Scholliers, Koopkracht en Indexkoppeling [Purchasing power index], p. 348.

- ↑ Mahaim, Ernest: Vue d’Ensemble, in: Mahaim, La Belgique Restaurée 1926, pp. 667-680; 673.

- ↑ Baudhuin, Histoire Economique 1946, p. 113.

- ↑ Scholliers, Loonindexering [Wage Index] 1985, pp. 71-76.

- ↑ Hogg, Structural Rigidities 1986, pp. 39-47; Veraghtert, De Industriële Ontwikkeling [The Industrial Development] 1981, p. 164.

- ↑ Chlepner, Les Finances 1926, p. 495.

- ↑ Hardewyn, Tussen Sociale Rechtvaardigheid [Between social justice and economic efficiency] 2003, pp. 81, 123.

- ↑ Van der Wee, La Banque Nationale 1997, pp. 35-40.

- ↑ Chlepner, Les Finances 1926, pp. 454-455.

- ↑ Scholliers, Loonindexering [[Wage Index] 1985, p. 38; Mahaim, La Fortune et le Bien-Etre 1926, pp. 505-611.

- ↑ Hardewyn, Tussen Sociale Rechtvaardigheid [Between social justice and economic efficiency] 2003, pp. 79-97.

- ↑ Hogg, Structural Rigidities 1986, pp. 126-128; Kurgan-Van Hentenryk, Ginette: Gouverner la Générale de Belgique: Essai de Biographie Collective, Brussels 1996, pp. 125-135.

- ↑ Kurgan-Van Hentenryk, De Société Générale 1997, pp. 238-260; Chlepner, Les Finances 1926, p. 497.

- ↑ Kurgan-Van Hentenryk, Gouverner la Générale 1996, p. 128.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 156.

- ↑ Van der Wee, Tavernier: La Banque Nationale 1975, pp. 41-44.

- ↑ Depoortere, L’Evaluation 1989, p. 752.

- ↑ Vanthemsche, De Val van de Regering Poullet-Vandervelde [The fall of the Poullet Vanderverlde] 1978, passim.

- ↑ Van der Wee, La Banque Nationale 1975, pp. 167-205.

- ↑ Kurgan-Van Hentenryk, De Société Générale 1997, p. 228.

Selected Bibliography

- Baudhuin, Fernand: Histoire économique de la Belgique, 1914-1939, 2 volumes, Brussels 1946: Etablissements Emile Bruylant.

- Depoortere, Rolande: L’evaluation des dommages subis par l’industrie belge au cours de la première guerre mondiale, in: Revue belge de philologie et d'histoire 67/4, 1989, pp. 748-769.

- Hardewyn, André: Tussen sociale rechtvaardigheid en economische efficiëntie. Een halve eeuw fiscaal beleid in België (1914-1962) (Between social justice and economic efficiency. Half a century of fiscal policy in Belgium (1914-1962)), Brussels 2003: VUBPRESS.

- Hogg, Robin L: Structural rigidities and policy inertia in inter-war Belgium, Brussels 1986: Koninklijke Academie voor Wetenschappen, Letteren en Schone Kunsten.

- Kurgan-van Henternryk, Ginette: Gouverner la Générale de Belgique. Essai de biographie collective, Brussels 1996: De Boeck Université.

- Kurgan-Van Henternryk, Ginette: De Société Générale van 1850 tot 1934, in: van der Wee, Herman / Verbreyt, Monique / et al. (eds.): Die Generale Bank, 1822-1997. Eine ständige Herausforderung, Tielt 1997: Lannoo, pp. 69-203.

- Mahaim, Ernest / Solvay, Ernest (eds.): La Belgique restaurée. Étude sociologique, Brussels 1926: M. Lamertin.

- Scholliers, Peter: Koopkracht en indexkoppeling. De Brusselse levensstandaard tijdens en na de Eerste Wereldoorlog, 1914-1925 (Purchasing power and index-linking. The Brussels standard of life during and after the First World War, 1914-1925), in: Revue Belge d'histoire contemporaine IX, 1978, pp. 333-382.

- Scholliers, Peter: The policy of survival. Food, the state and social relations in Belgium, 1914-1921, in: Burnett, John / Oddy, Derek (eds.): The origins and development of food policies in Europe, London; New York 1994, pp. 39-53.

- Scholliers, Peter, Centrum voor Hedendaagse Sociale Geschiedenis, Vrije Universiteit Brussel (ed.): Loonindexering en sociale vrede. Koopkracht en klassenstrijd in België tijdens het interbellum (Wage index and social peace. Purchase power and class struggle in Belgium in the interwar period), Brussels 1985.

- van der Wee, Herman / Tavernier, Karel: La Banque nationale de Belgique et l'histoire monétaire entre les deux guerres mondiales, Brussels 1975: Banque nationale de Belgique.

- Vanthemsche, Guy: De val de Regering Poullet-Vandervelde een ‘Samenzwering der Bankiers’? (The fall of the Poullet-Vanderverlde. A ‘conspiracy of the bankers’?), in: Revue Belge d'histoire contemporaine IX, 1978, pp. 165-211.

- Veraghtert, Karel: De Industriële Ontwikkeling (1914-1947) (The industrial development (1914-1947)): De industrie in België. Twee eeuwen ontwikkeling 1780-1980 (The industry in Belgium, two centuries of development (1780-1980)), Brussels 1981: Gemeentekrediet van België; Nationale Maatschappij voor Krediet aan de Nijverheid, pp. 145-188.