Introduction↑

War photography started shortly after the official announcement of the invention in 1839. The earliest daguerreotypes of the Mexican-American war in the 1840s were soon followed by photographs of the Crimean War (1853-1856) and of the American Civil War (1861-1865), all of which were taken by professional photographers with bulky cameras and glass negatives. By the time the Great War broke out, however, photography was more than seven decades old. During that time, it had undergone a number of developments that made it more accessible and reduced the size of its equipment. With the development of the duplex camera and celluloid film in the 1880s, anybody who could afford a camera was in a position to take relatively good images. And with the subsequent development of smaller, lightweight cameras such as Kodak’s 1912 vest pocket camera (VPK) and the German Ibsor camera, developed by the A. Gauthier company (1913), it became even more accessible.

By the beginning of the Great War several types of “pocket cameras” were readily available. Not only did armies have their own official photographers, but the popularity of photographs in print journalism encouraged many photo-journalists to capture scenes on the front and in the diplomatic arena. Some army officers even carried their own pocket camera while at the front, despite a ban on the photographing of military installations that sought to protect armies from espionage.

British Photographers on the Ottoman Front↑

Among the best known photographs taken in Arabia on the eve of the Arab revolt in 1917, were those taken by the American journalists Lowell Thomas (1892-1981) and photographer Harry Chase (1883-?).[1] The bulk of their images were of Lawrence of Arabia, or Thomas Edward Lawrence (1888-1935). Camera enthusiasts, captains F. S. Newcombe, H. Garland and Raymond Goslett, who were in Arabia with T. E. Lawrence, also took a number of pictures of events at the time. On the Palestine front, Colonel Stanley Byrne of the 1/11 London regiment - whose unit was attached to the Desert Column - photographed the British Gaza campaign. During the same campaign, Private George Westmoreland photographed El-Arish (southern Palestine) at the request of General Archibald Murray (1860-1945).[2] In Iraq, three enthusiasts who accompanied the British-Indian garrison at Kut al-Amara took photographs of battles, field hospitals, military hardware, trenches, troops, and Ottoman prisoners of war. They were Major A. S. Cane of the Royal Army Medical Corps, Reverend Harold Spooner of the Church of England, and Major P. C. Saunders. The work of these British amateur soldier photographers in Arabia, Palestine and Iraq appeared occasionally in publications such as The War Illustrated and the London Illustrated News.

Australian photographers Frank Hurley (1885-1962) and Hubert Wilkins (1888-1958) were the official photographers of Anzac troops dispatched by the British to the Turkish Straits. They produced images of the Dardanelles Campaign at Gallipoli (Çanakkale Savaşı) on the Turkish Thrace in 1915 which are housed at the Australian War Memorial Museum.[3]

German Photographers of the Armenian Genocide↑

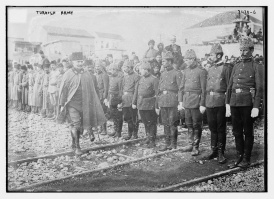

The Ottoman fronts were also photographed, although perhaps less than the western fronts of Europe. Images of Ottoman or German leaders, troops, and major events are not hard to find in electronic archives. The collection of Erwin Biesenbach, for instance, shows troops and leaders on various fronts in the Middle East and in Europe. However, it is not known whether Biesenbach was only the collector or the actual photographer of the images. Second Lieutenant Armin T. Wegner (1886-1978), who witnessed the genocide of the Armenians while stationed with Ottoman forces, also took a large number of photographs of the deportations, the dead, and the encampments in 1915-1916. His photographs of the Armenian plight in the Syrian Desert ultimately lead to his arrest but they are currently among the few known images of the tragedy available.[4]

Native Photographers of Ottoman Troops↑

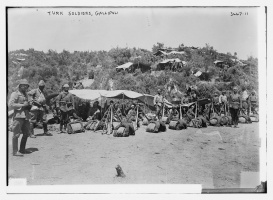

Ottoman nationals also took photographs on the various eastern fronts, although the information available about them is often rather sketchy. Signed or stamped pictures from the war on the Ottoman front are, indeed, rather hard to find. The few names that we know were primarily of professional photographers whose collections survived. Ottoman army photographers, including soldiers specifically assigned to the task, seem to have worked anonymously and to have been directed carefully on what and how to photograph by their superiors. Their role appears to have been closer to that of a technician than to that of an artist.

Known studio photographers working in cities such as Istanbul, Aleppo, Damascus, Beirut, and Jerusalem photographed troops and events that took place near them. They also produced numerous studio portraits of conscripts before they headed to the front. Armenian photographers largely dominated in the field of studio photography in the major cities. Some studied at the Armenian Mourad Raphaelyan School in Venice to become pharmacists and chemists and subsequently became interested in the chemical aspects of photography; others studied photography in Jerusalem at the school set up by Yassay Garabedian (1825-1885). At their hands, a number of non-Armenians learned the trade.[5]

Photographers of the Fourth Ottoman Army↑

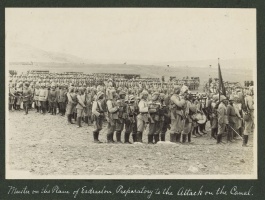

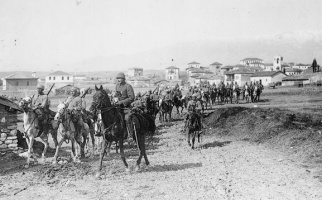

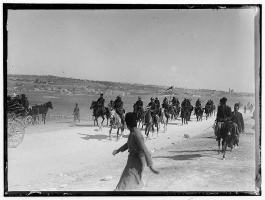

The Ottoman army had a few official photographers such as Burhan Felek (1889-1982) who was the official photographer to the army headquarters in Istanbul, Arif Hikmat Koynoğlu (1888-1982) who fought on the Russian-Caucasian front, and both Esat Nedim Tengizman (1898-1980) and Etem Tem (1901-1971) who were on the Caucasian front.[6] However, while the few known images of Ottoman officers at Gallipoli were taken by photographers whose names are unknown to us, the case was rather different with the Ottoman Fourth and Eighth Armies stationed in Syria. In Palestine, photographer Khalil Ra’ad (1854-1957) advertised himself as the official photographer of Ahmed Cemal Pasha (1872-1922), the leader of the Fourth Army.[7] Ra’ad was an apprentice of the Armenian photographer Garabed Krikorian (1847-1920) - a former student of Garabedian himself. The Jerusalem-born American John Whiting (1882-1951), a member of the missionary group known as the American Colony and one of the photographers in their photography department, also claimed to be the photographer of Cemal Pasha.[8] Both Ra’ad and Whiting appear to have been at the same locations on the southern Palestine front during the preparations for the Ottoman Suez campaign in 1915 and later on in 1917. They took images of troops performing drills, officers in their tents and wounded soldiers in hospitals. They also produced portraits of army leaders. The Whiting collection is housed at the library of Congress while the Ra’ad collection is at the archives of the Institute for Palestine Studies in Beirut.

The bulk of Whiting’s war photographs consists of over 200 images taken during the Suez campaign, depicting military activities and battlefield locations. The collection includes pictures of flotillas transporting grain from the eastern to the western shores of the Dead Sea, field hospitals, troop movements, and the shutting down of foreign postal services in Jerusalem following the annulment of the capitulation agreements between the Ottomans and several European countries.

The Ra’ad collection includes similar and, in at least one case, identical images to those taken by Whiting - a fact that suggests that the two might have worked closely together. However, Ra’ad appears to have specialized in portrait photography. We find images of Cemal Pasha with his staff in front of various governmental buildings in Jerusalem, Beir al-Sabi’ (Beersheba) and Damascus. He also took a number of studio portraits of, among others, Mehmed Kâmil Pasha (1833-1913), the head of the Eighth Ottoman Army, Captain Werner von Frankenberg und Proschlitz (1868-1933), the German commander of the Asian Korps (Asien-Korps), and Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein (1870-1948), assigned to the Ottoman army during the Suez campaign.

A number of photographs of troops in Damascus and Aleppo are also available. These were likely taken by one of the few professional photographers in the city, such as the Aleppo-based Armenian Derounian brothers, Vartan, Hagop, and Phillipe.[9] Similarly, photographs of Ottoman leaders in Istanbul, including Ismail Enver Pasha (1881-1922), were likely taken by one of the city’s many Armenian photographers, such as Boghos Tarkulyan (1882-1936), whose studio was known as Atelier Phébus. In Beirut, the brothers, Abraham Sarafian (1873-1926), Bogos Sarafian (1876-1934), and Samuel Sarafian (1884-1941), photographed Armenian refugees arriving in Lebanon during the war. Themselves Armenians, the Sarafians were refugees from Diyarbakır who arrived in Beirut in the aftermath of the massacres of 1895.[10]

Conclusion↑

The large number soldiers’ studio portraits found in family and private collections are as valuable for historians as the images of the leaders or the fronts. The Ottomans used photographs in their propaganda campaign and the available images from the front rarely showed death or disaster. They tended to be selective and staged and often depicted officers inspecting the troops or doctors and nurses tending to the wounded soldiers. Most of the photographs appear to have been produced at the behest of institutions that commissioned photographers to document their activities during the war. Such institutions included the Ottoman Red Crescent Society, the Fourth and Eighth Armies, and various important offices of the empire.

Issam Nassar, Illinois State University

Section Editors: Elizabeth Thompson; Mustafa Aksakal

Notes

- ↑ Carmichael, Jane: First World War Photographers, New York 1989, p. 81. For Thomas’s own account, see Thomas, Lowell: With Lawrence in Arabia, Whitefish 2005.

- ↑ Carmichael, First World War Photographers 1989, p. 78.

- ↑ For more information see: Dixon, R.: Spotting the fake: C.E.W. Bean, Frank Hurley and the making of the 1923 photographic record of the war, in: History of Photography 31/2 (2007), pp. 165-179.

- ↑ Wegner's biography is available at: http://www.armenian-genocide.org/wegnerbio.html (retrieved 29 February 2016).

- ↑ For further information on the role of Armenians in early photography, see Miller, Dickinson Jenkins: The Craftsman’s Art: Armenians and the Growth of Photography in the Near East (1856-1981), Master of Arts thesis, American University of Beirut, 1981.

- ↑ Özendes, Engin: Photography in the Ottoman Empire, 1839-1919, Turkey 1987, pp. 315-319.

- ↑ Nassar, Issam: Photographing the Fourth Army and the Suez Campaign. In: Jerusalem Quarterly 56 & 57 (2014), p. 70.

- ↑ Nassar, Issam: John Whiting’s Album of the Great War in Palestine. In: Jerusalem Quarterly 53 (2013), pp. 42-49.

- ↑ For further information on the photographers of Damascus, see El-Hajj, Badr: Des photographes à Damas: 1840-1918, Paris 2000.

- ↑ The Sarrafian Brothers, at: http://www.onefineart.com/en/artists/sarrafian_brothers/index.shtml (retrieved 29 February 2016).

Selected Bibliography

- Carmichael, Jane: First World War photographers, London; New York 1989: Routledge.

- Collins, Douglas: The story of Kodak, New York 1990: H. N. Abrams.

- El-Ḥājj, Badr: Des photographes à Damas, 1840-1918, Paris 2000: Marval.

- Holborn, Mark / Roberts, Hilary (eds.): The Great War. A photographic narrative, London 2013: Imperial War Museum; Jonathan Cape; Knopf.

- Holmes, Richard: The First World War in photographs, London 2001: Carlton Books.

- Hurley, Frank, Dixon, Robert / Lee, Christopher (eds.): The diaries of Frank Hurley, 1912-1941, London 2011: Anthem Press.

- Nassar, Issam: Familial snapshots. Representing Palestine in the work of the first local photographers, in: History & Memory 18/2, 2006, pp. 139-155.

- Özendes, Engin: Photography in the Ottoman Empire, 1839-1919, Istanbul 1987: Haşet Kitabevi.

- Sheehan, Tanya: Photography, history, difference, Lebanon 2014: Dartmouth College Press.