Introduction: The Legal Framework. Espionage and Danish Criminal Law↑

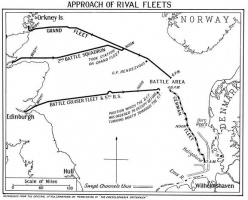

The existence of facilities for foreign communications were decisive for the presence of foreign intelligence services in Denmark. Danish state telegraph cables connected, via the Great Northern Telegraph Company’s undersea cables, to France, Great Britain, Norway, Sweden, Russia, and Germany. On 31 July 1914, the Danish government cut telephone connections to Germany. In the following weeks, communications surveillance and a ban on encrypted messages were introduced, later followed by official censoring. However, during the entire war, embassies in Copenhagen could communicate with their respective governments through encrypted telegrams and diplomatically protected mail. This meant that all intelligence activities were centred around the embassies. The German intelligence services also had agents just north of the border who could quickly reach German territory and telephone information, for example, to the naval bases at Wilhelmshaven and Kiel.[1]

In Danish criminal law before 1914, espionage was a violation of both the military and civilian penal code, but the provisions were only applicable during wartime. Only following Acts No. 150 and 151 of 2 August 1914 could spies be prosecuted in peacetime. Prosecution could only take place on the orders of the Minister of Justice so that the government could refrain from prosecution if it was politically opportune. From 1913 to 1920, Denmark had a social liberal and anti-militarist minority government with Social Democrats as parliamentary basis. The government’s strategy was that cases of espionage should pass unnoticed and attract neither domestic public nor foreign attention. The Minister of Justice pursued a policy of only filing charges in serious cases – and not in cases of counter-espionage, even when this was possible. As a result, during the war only forty-eight persons were convicted and sixty-four expelled from the country for contravening Acts no. 150 and 151 of 1914.

Espionage was nevertheless very present in the public consciousness as well as in the authorities’ confidential archives. At the time, all of Europe suffered from both a fascination with, and fear of, espionage. In Denmark, spy novels were written, plays staged about spies, and countless newspaper articles on spies were published. The archives show that about 1,000 people were investigated and registered in the so-called spy directory as a result.

The international situation prior to 2 August 1914 led the German, British, and Russian intelligence services to initiate brisk activities in Denmark. Operating in Danish territory was cheap and risk-free in comparison with Germany, for example, where convicted spies received lengthy prison sentences. The British and Russians therefore used Danish territory as much as possible to obtain intelligence regarding the German fleet. The German intelligence gathering in pre-war Denmark had various purposes: first, to monitor activities that were hostile to Germany; second, to recruit agents to support the German military in the imminently expected major war; and third, to gather intelligence on the Danish military and topography to facilitate operational plans for an attack on Denmark, which the staff officers in Berlin worked on several times.

Although foreign intelligence services could exploit Danish territory unpunished, their activities were, as far as possible, monitored intensely by Denmark’s General Staff, which meant that the technical know-how and practical experience lay in the hands of military intelligence officers rather than civilian authorities. That Danish counter-espionage efforts were efficiently organised and fully expanded before war broke out, and that this expertise resided with the General Staff, would prove significant during the course of the war.

The Danish Military Intelligence Service↑

In 1866-67, the Ministry of War created a secret intelligence service and transferred its operation to the General Staff's tactical department in 1873. In 1903, the department was subdivided, following the French model, into four bureaus and the intelligence service was placed in the “2nd Bureau”, which in 1911 changed its name to Generalstabens Efterretningssektion or GE (General Staff Intelligence Section). Officers headed three covert organizations named the foreign intelligence service, the preventive intelligence service, and the domestic intelligence service which were established in 1866, 1898, and 1900, respectively.

The primary purpose of the foreign intelligence service was to provide timely warning in the event of invasion – a German attack on Denmark. It was expected that an attack would take place using German land troops moving up through Jutland at the same time as the German Fleet sailed to Køge Bay and landed troops in the vicinity of Copenhagen. Agents were therefore recruited in German ports along the Baltic and along the Kiel canal as well as the rail line from Hamburg up to the then Danish-German border. The agents were told to monitor gatherings of transport vessels, materiel, and troops. GE had around fifteen agents in Germany, all of whom belonged to the Danish minority. Their coded messages could be sent as letters, telegrams and as advertisements in local German newspapers. This system diminished in significance during the war due to the stringent controls imposed on communications. Instead, GE used “legal travellers” for gathering intelligence abroad – Danish tourists and business people who received instructions from GE before departure and who were then debriefed on their return to Denmark. The Danish German border was easy to cross and all military activity in Schleswig was closely scrutinised.

The domestic intelligence service was established with a view to setting up a dormant network of informers to be activated in the event of a hostile occupation of Denmark (equivalent to the later “stay-behind” network). By 1914, this had developed into a permanently operational counter-espionage service that both before and during the war kept GE informed about all suspicious circumstances that might indicate French, British, German, or Russian intelligence activities in Denmark. At the outbreak of war, approximately 1,500 people had signed up and received instruction and training in the areas where GE required information. The organisation was built hierarchically, consisting of group leaders, district chiefs, and regular agents who were frequently asked by GE to perform various investigation and surveillance tasks. Leaders of German espionage efforts in Denmark were, to the best of the agents’ ability, shadowed everywhere. Investigations of spies were most often initiated because an agent discovered a suspicious situation and kept it under observation. If GE judged that there was a case, the material gathered was handed over to the police authorities, who then continued the investigation. After the war, the General Staff concluded that the organisation had functioned excellently and decided to continue it with reference to the “Bolshevik peril”.

The preventive intelligence service was not an organisation, but an umbrella designation for all counter intelligence activities. All investigation of suspected spies was archived by GE and a name directory was drawn up, which exceeded 1,000 entries in 1918. Information did not come exclusively from agents in the domestic intelligence service but also from postal and telegraph services. During the war, both GE and the police had the power to request telephone wire taps and the interception of letters and telegrams in spy cases. From 1911, GE was led by Captain Erik With (1869-1959) who had previously served with the intelligence service from 1904 to 1908. He was part of a strongly pro-French and pro-British group of officers, and his German counterparts (and the Danish government) attempted to have him removed. In 1918 Captain Niels Frederik Herholdt Sylow (1877-1958) took over as chief of GE, while With – after a protracted power struggle with the defence minister – was transferred to a position as battalion commander in Holbæk. From private notes and diaries, however, it appears that With, through intermediaries and weekly meetings with Sylow, managed to maintain the leadership of GE for the duration of the war.

International Intelligence Cooperation↑

The Danish officer corps before 1914 was primarily pro-French, and both before, during, and after the war, covert Danish-French collaboration took place in the field of intelligence. During the war, GE also supported Norwegian, British, and US intelligence officers. A close collaboration existed throughout the war between Erik With and the chief of the Norwegian General Staff’s intelligence section, Trygve Frivold Graff-Wang (1875-1952), with the Norwegian military attaché in Copenhagen, Oswald Nordlie (1881-1954), acting as go between. The cooperation was sanctioned by the chiefs of the general staffs of the two neutral countries in August 1914 and was regarded as ideal from the Danish side. The American naval intelligence officer, John Gade (1875-1955) was in Copenhagen in the last year of the war and established a close cooperation with Erik With. They both had Norwegian wives, shared common acquaintances in Norway, and met privately and with Nordlie. In the years 1918, 1920, and 1921 respectively, Erik With was decorated with Norwegian, French, and British orders of chivalry. GE however, did not have a similar collaboration with the Swedish General Staff, who traditionally had strong ties to Prussia (and secretly collaborated with Berlin during the war).

German intelligence activities in Denmark↑

The German army and navy each had their own intelligence service. The army’s – Abteilung IIIb des Großen Generalstabes (IIIb) – and the navy’s – Nachrichtenabteilung des Admiralstabes der Marine (“N”) – also each had their own agents in Denmark. As war approached, “N” set up a Zentralstelle Kopenhagen, whose agents covered Danish territorial waters and ports and served as an advance warning system. Given any indications that the British Royal Navy was attempting to penetrate the Baltic, the agents were to send a pre-agreed telegram to Germany, in order to notify the naval base at Kiel as quickly as possible. The agents’ primary task was to supply German U-boats with information on shipping traffic. In order to target the correct merchant vessels and thereby cut Britain off from supplies, the German admiralty was dependent on information regarding merchant ships’ cargoes, appearance, sailing times, and routes. Naval intelligence was also gathered from German territory. At the zeppelin airfield in Tondern, codebreakers successfully cracked the Danish military code system and could decipher internal Danish radio communication containing messages about North Sea maritime traffic. Approximately 200 Danish merchant vessels were sunk by German U-boats.

The army’s intelligence-gathering in Denmark was led by Oberkommando Küste in Hamburg and the subsidiary departments Nachrichtenstelle Flensburg and Nachrichtenstelle Hadersleben. Rumours about British plans for a landing in Jutland were reported and taken seriously in the spring of 1915. The chief of IIIb, Walter Nicolai (1873-1947), therefore issued an order on 30 April 1915 to start “a comprehensive surveillance of the entire Danish military”[2] and prepare an outline of options to execute acts of sabotage against railways and bridges in Jutland in the event of a British invasion. Based on the gathered intelligence, a plan of attack against Denmark, named Fall J, was drawn up by the Admiralty and General Staff in Berlin in the autumn of 1916 and was signed by Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) in December.

In the autumn of 1914, the Spionageabwehr Schleswig (Schleswig counterintelligence) was established. Its headquarters in Flensburg were manned by former police detectives from Schleswig, but it was a military body under the auspices of IIIb with responsibility for “counterintelligence in Germany and neutral countries”.[3] The department undertook postal and telegraph surveillance to and from Denmark and police investigations of espionage in Schleswig as well as Danish territory. North of the border, the department had plainclothes officers posted in Jutland station towns between Esbjerg and Kolding, who, with the support of the German consulates, investigated espionage against Germany in Jutland.

In spring 1915, the German ambassador to Copenhagen, Ulrich Graf Brockdorff-Rantzau (1869-1928), complained to Foreign Minister Erik Scavenius (1877-1962) that the Entente was using Danish territory as a stepping stone to conduct espionage against Germany and requested that German Police be authorized to investigate espionage hostile to Germany in Denmark in cooperation with Danish police. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Justice then concluded a secret agreement with Brockdorff-Rantzau that an office in Copenhagen would be established consisting of German police and officers who pledged themselves to solely investigate espionage that was hostile to Germany. The scheme was kept secret both from GE and the Entente ambassadors in Copenhagen. This clandestine favouring of German interests was discovered by GE, who then placed the German officials under surveillance. After the war, the opposition in parliament demanded a review and sharply criticised the scheme, contending that it was incompatible with the country’s stated neutrality.

In addition to the gathering of intelligence outlined here, German intelligence services carried out a long list of other covert activities on Danish soil: abductions, weapons theft, smuggling, financial fraud, propaganda, and subversion.

Russian Intelligence Activities in Denmark↑

Both before and during the war, the Russian embassy in Copenhagen was extensively employed as a staging ground for Russian espionage in Germany. Polish-born General Staff officer, Sergei Potocki (1877-1953), who was a colonel and attaché in 1914, directed these activities. After the war, the German intelligence chief, Walter Nicolai, wrote that Copenhagen became “the centre for Russian espionage against Germany” because “the Russian Secret Service was favoured by the authorities in Denmark”.[4] This is not entirely true. The choice of Danish territory as a transit area and base of operations was primarily because the country offered easy ingress to and egress from Germany via its land border and the many ferry routes from German ports to Denmark and southern Sweden as well as the previously mentioned direct telegraph cable between Copenhagen and Russia. Another reason was the prevailing anti-German sentiment among the Danish population, which proved fertile ground for the recruitment of spies. The Danish royal family had for decades a close relationship with the Russian royal house, as Maria Fedorovna, Empress, consort of Alexander III, Emperor of Russia (1847-1928) was born a Danish princess, but there were no formal ties to Danish authorities and the Russian intelligence service in Denmark only received assistance from private individuals.

British Intelligence Activities in Denmark↑

In the decade before the outbreak of war, the War Office and Admiralty worked on the possibility of forcing the Danish straits and thereby threatening the German Baltic coast in the event of war. In connection, Copenhagen was conceived as being the primary platform for gathering intelligence from Germany. The direct telegraph connection across the North Sea ensured a rapid line of communication to Whitehall and Denmark’s location was optimal in relation to gathering information about the German fleet, German coasts, ports and shipyards. In addition, there was an expectation that “Danes in many ways make the best S.S. agents for employment.”[5] The offensive against the German Baltic coast was never realised, however, and the British presence in Denmark never became as comprehensive as in the Netherlands.

British activities in Denmark during the war generally had three purposes: military espionage in Germany with Denmark as an operating base, monitoring of German naval movements in Danish waters, and investigation of covert German activities in Denmark (especially the combatting of German espionage with the purpose of protecting supplies to Britain as well as detection of German attempts to circumvent the blockade through smuggling and fraud). There were around 100 British agents in Denmark who were given code names D1, D2, etc. The leading operative in London was Frank Noel Stagg (1884-1956) who in the autumn of 1914 was transferred to Mansfield Cumming’s (1859-1923) small organisation, MI1c (later to become MI6/SIS). According to Stagg, at that point MI1c only had five employees and “I took over all the NID liaison, Scandinavia and the Baltic, and the Russian Empire!”[6] The leading operatives in Denmark were the accredited attachés at the embassy as well as artillery officer Richard Holme (1877-1972).

A number of Danish historians have combed the British archives and concluded that, in addition to the British diplomatic corps, the consular corps and the D agents, the most important intelligence came from GE and from the small circle around Christian X, King of Denmark (1870-1947), consisting of Alexandrine, Queen, consort of Christian X, King of Denmark (1879-1952), the princes, and businessman H.N. Andersen (1852-1937). Going behind the government’s back, they supplied confidential intelligence on German military. As early as the autumn of 1914, the commanding admiral suspected Vice Admiral Georg, Prince of Greece and Denmark (1869-1957) and, with government approval, cut him off from further information. Beyond this, there is nothing to indicate that the government was aware of the king’s duplicity. The motivation for both GE and the royal family was a dream of regaining the lost duchy of Schleswig from the victors following a German defeat.

French Intelligence Activities in Denmark↑

The French naval attaché in Berlin, Gontran-Marie-Auguste de Faramond (1864-1950), was transferred to Copenhagen when war broke out, whence he assisted British- and Russian-financed intelligence efforts. Around the turn of the year 1914-1915, French intelligence officers were involved in setting up a prisoner of war camp in southern France for Danish speaking captives from Northern Schleswig. The following year the French intelligence service initiated independent operations in Denmark with its own agents. The purpose was to carry out espionage in Germany and to interrogate German deserters who crossed the border into Denmark. To facilitate this, a close collaboration began with GE and with the committee of the association Two Lions (a conservative academic association that provided support for Danes in Schleswig). The 2,500 Northern Schleswig soldiers who deserted during the war and crossed the border were systematically interviewed on every subject they were willing to reveal. The Danish-French agreement was that all information which French-financed agents succeeded in acquiring was also to be shared with GE.

In the spring of 1918, however, things went awry. The French networks were infiltrated by German agents who obtained evidence of hostile espionage against Germany. This material was handed over to the Danish Ministry of Justice via middlemen, who alleged that the material originated from anonymous Danish officers. Twenty-two persons were charged, including Erik With, but the Danish foreign minister intervened and had the case shelved while promising Brockdorff-Rantzau that With had been removed from GE and that all parties would be punished should the activities continue. One of the accused was, however, arrested and convicted by the Reichsgericht in Leipzig in 1919 when he returned home to Germany. After a year’s imprisonment he was pardoned and returned home to Northern Schleswig (now Denmark) where his actions divided public opinion. At the French embassy in Copenhagen in 1922 he was awarded an order of chivalry, but among veterans in Southern Jutland he, along with the other spies, remained an object of hate and was accused of being the cause of the high losses suffered by the “Danish regiments” in the German army.

Conclusion↑

An American journalist travelled around Europe 1915 and characterized Copenhagen as “the Mecca of European secret service work”.[7] While that assessment is debatable, it is evident that Danish territory was a favoured residence for intelligence officers, spies, smugglers, and others embroiled in clandestine activities bankrolled by the warring states.

Turning to the Danish perspective, the field of intelligence demonstrates that reality was far from the official policy of neutrality. The government found it necessary to secretly favour Germany to reduce the risk of a German occupation of the country, while GE, the royal family, and parts of the political opposition favoured Germany’s enemies. From the summer of 1915, GE was involved in a conspiracy to topple the government and halt the pro-German foreign policy. In general, GE was no tool of the government, but made itself available for the king, the opposition and the Entente. The aim was to build goodwill with the Entente that would be necessary if conservative Denmark’s wish for a German defeat and the Danish king’s reclamation of Schleswig was to become a reality. GE succeeded only partially – the necessary French goodwill was achieved but the goal itself was not, as only the northern third of Schleswig “returned home”.

During the German occupation during the Second World War (1940-1945), the relations between GE, the government, and abroad were in many ways repeated on a larger scale. The government accepted German occupation and the Danish authorities had a wide-ranging collaboration with German authorities, while GE, behind the backs of both the Danish government and the German occupation forces, assisted the SIS and SOE.

Kristian Bruhn, University of Copenhagen

Section Editor: Nils Arne Sørensen

Notes

- ↑ This article is primarily based on the author’s studies in Danish, British, and German archives from 2013-2017. Detailed references will be presented in the forthcoming Danish-language monograph on the development of the Danish military intelligence service from the Schleswig Wars to the First World War. I am grateful to Mads Lykke Hjortgaard for a copy of his unpublished MA thesis.

- ↑ Bundesarchiv Militär-Archiv, Freiburg. RW5/47. Der Gempp-Bericht, Bd. VII, p. 126

- ↑ Landesarchiv Schleswig-Holstein. Abteilung 301. Oberpräsidium. File 1799 “Spionageabwehr.”

- ↑ Nicolai, Walter: German Secret Service, London 1924, p. 99.

- ↑ Jeffery, Keith: MI6. The History of the Secret Intelligence Service, 1909-1949, London 2010, p. 23

- ↑ Judd, Alan: The Quest for C. Sir Mansfield Cumming and the Founding of the British Secret Service, London 1999, p. 318

- ↑ Bernhart, Paul Holst: My Experience with Spies in the Great European War, Chicago 1916, p. 93.

Selected Bibliography

- Andersen, Morten: Oluf Wolf og den franske forbindelse. En sønderjysk spionagesag under 1. verdenskrig (Oluf Wolf and the French connection. A Northern Schleswig spy case from The First World War), in: Sønderjyske Årbøger 1, 2010, pp. 33-68.

- Bradley, J. F. N.: The Russian secret service in the First World War, in: Soviet Studies 20/2, 1968, pp. 242-248.

- Brandal, Nik. / Teige, Ola: The secret battlefield. Intelligence and counter-intelligence in Scandinavia during the First World War, in: Ahlund, Claes (ed.): Scandinavia in the First World War. Studies in the war experience of the northern neutrals, Lund 2012: Nordic Academic Press, pp. 85-108.

- Christmas-Møller, Wilhelm: Christmas Møllers politiske læreår (Christmas Moller’s early political career), Copenhagen 1983: Vindrose.

- Christmas-Møller, Wilhelm: Forsvarsminister P. Munchs opfattelse af Danmarks stilling som militærmagt. Belyst ved hans forvaltning af sit ressort 1913-20 (Defense Minister P. Munch's view of Denmark's position as a military force. Illuminated by his management of his area 1913-20), in: Danmark og det internationale system. Festskrift til Ole Karup Pedersen (Denmark and the international system. Commemorative essays for Ole Karup Pedersen), 1989.

- Clemmesen, Michael H.: Den lange vej mod 9. april. Historien om de fyrre år før den tyske operation mod Norge og Danmark i 1940 (The long road towards 9 April. The story about the forty years before the German operation against Norway and Denmark in 1940), Odense 2010: Syddansk Universitetsforlag.

- Clemmesen, Michael H.: Det lille land før den store krig. De danske farvande, stormagtsstrategier, efterretninger og forsvarsforberedelser omkring kriserne 1911-13 (The small country before the Great War. Danish territorial waters, Great Power strategies, intelligence and defence preparations before, during and after the crises 1911-13), Odense 2012: Syddansk Universitetsforlag.

- Devenny, Patrick: Captain John A. Gade, US Navy. An early advocate of central intelligence, in: Studies in Intelligence 56/3, 2012, pp. 21-30.

- Dunley, Richard: ‘Not intended to act as spies’. The Consular Intelligence Service in Denmark and Germany, 1906-14, in: The International History Review 37/3, 2015, pp. 481-502, doi:10.1080/07075332.2014.942677.

- Futrell, Michael: Northern underground. Episodes of Russian revolutionary transport and communications through Scandinavia and Finland, 1863-1917, London 1963: Faber and Faber.

- Gade, John A.: All my born days. Experiences of a naval intelligence officer in Europe, New York 1949: Scribner's.

- Hedegaard, Ole A.: En general og hans samtid. General Erik With mellem Stauning og kaos (A general and his time. General Eric With between Stauning and chaos), Frederikssund 1990: Thorsgaard.

- Jeffery, Keith: MI6. The history of the Secret Intelligence Service 1909-1949, London 2010: Bloomsbury.

- Judd, Alan: The quest for C. Mansfield Cumming and the founding of the British secret service, London 2000: HarperCollins.

- Kaarsted, Tage: Great Britain and Denmark 1914-1920, Odense University Studies in History and Social Sciences, Odense 1979: Odense University Press.

- Lange, Ole: Jorden er ikke større... H. N. Andersen, ØK og storpolitikken 1914-37 (The earth is not larger… H. N. Andersen, EAC and foreign policy 1914-37), Copenhagen 1988: Gyldendal.

- Marklund, Andreas: Listening for the state. Censoring communications in Scandinavia during World War I, in: History and Technology 32/3, 2016, pp. 293-314.

- Rintelen, Franz von: The dark invader. Wartime reminiscences of a German naval intelligence officer, London 1933: Lovat Dickson.

- Scharlau, Winfried Bernhard / Zemann, Zbyněk A. B.: The merchant of revolution. The life of Alexander Israel Helphand (Parvus), 1867-1924, London 1965: Oxford University Press.