Background to the Leizpig Trials↑

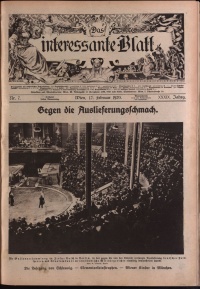

In 1921 and 1922, a total of twelve “war crimes” trials were held before the highest German court, the Reichsgericht in Leipzig. The accused were former members of the imperial German armed forces suspected of having perpetrated war crimes. At first, in keeping with Articles 228 and 229 of the Treaty of Versailles, the Allied powers had planned that as many as 900 Germans accused of war crimes would be extradited and face trial in allied courts. However, the German government succeeded in averting their extradition. Instead, it emphasized that it was willing to prosecute all Germans accused of committing crimes against nationals of enemy states or against enemy property, underscoring this promise with changes in German laws.

The Allies acquiesced and on 7 May 1920 they presented a much shorter list with the names of forty-five suspects and the details of their alleged crimes. The list was accompanied by an official note, stating that the intention of this first compilation was to ascertain the seriousness of the Germans’ self-commitment and that this new list was nothing more than a “test”.

The First Trial↑

The first trial of alleged war crimes and other offences in Leipzig began on 10 January 1921. It was the result of the application of the legality principle, since the three accused, soldiers from an engineering corps, had neither been named on the “test list”, nor on the earlier extradition list. The attorney general accused them of robbing a Belgian innkeeper towards the end of the war. The accused confessed and two of them, who had used weapons during the robbery, were convicted of looting and sentenced to four and five years in jail respectively; the third soldier received a two-year sentence. Legal norms set down in the German military’s criminal code were the basis for these proceedings.

Further Trials↑

The trials of those named on the “test list” finally commenced in May 1921. The first four cases were brought to trial at the insistence of the United Kingdom. Of these, three involved abuse of prisoners of war, mostly beatings of British prisoners of war. The Reich Supreme Court handed down a ten-month sentence against the commander of a smaller camp, a former non-commissioned officer. Another camp commander, a former captain, was to serve six months, as was a soldier who had been a camp guard. Here again, the court based its rulings on the German military code. The fourth case dealt with charges that a British hospital ship had been sunk in the course of German submarine warfare. The submarine commander was acquitted on grounds that he had been acting on orders from his superiors.

The accusations brought forward by Belgium and France pertained, in the first trial, to a member of the Secret Military Police charged with assault, torture, and illegal restraint in the context of an interrogation of Belgian children; this man was acquitted. Executions of imprisoned or wounded French soldiers and abuse of prisoners of war were the charges in the other five French cases. In four of these, the accused - higher to highest ranking officers - were found not guilty. One major was convicted of manslaughter and received a two-year sentence; here, the court assessed the crime according to international laws and customs of war.

The final case tried in 1921 again dealt with an attack on a hospital ship as part of unrestrained submarine warfare. The key figure, a lieutenant captain and submarine commander, who Great Britain hoped would be convicted, was a fugitive. Instead, two former crew members, naval lieutenants, stood trial and were sentenced to four-year jail terms each as accessories to manslaughter. Again, the court referred to international law and customs of war in reaching its decision. After the trial, however, the two men sentenced spent only a few weeks in jail before they escaped from prison and fled Germany. The court’s decision was rescinded by the Reich Supreme Court in 1928 and both officers were acquitted.

The last two trials occurred in 1922. A physician accused of murdering and abusing sick or injured soldiers by the French was found not guilty on grounds that the proceedings had failed to produce “even a sliver of evidence,” a claim also made in other cases in which the suspects were acquitted. The attorney general investigated according to the legality principle in the case of other soldier, who was subsequently convicted of looting according to the military code and received a two-year jail term.

The Allies, and in particular France, responded by sharply criticizing the first decisions reached, referring to what was happening at the trials as a “farce” and a “comedy”. In contrast to their original announcement, however, the Allies did not insist that the accused be extradited. Instead, they discontinued any form of cooperation with the Reich Supreme Court in Leipzig. This outcome was welcomed in Germany, where the court subsequently lacked sufficient evidence to conduct any further trials. Thus, by 1927, the proceedings were ended in more than 1,700 cases, either by court decisions or as a result of decisions made by the attorney general. For the Allies during the Second World War, the conclusions were clear: it was not to be left to German courts to try and punish German war criminals. Nuremberg was the response to the Leipzig war crime trials.

Gerd Hankel, Hamburger Institut für Sozialforschung

Section Editor: Mark Jones

Selected Bibliography

- Hankel, Gerd: Die Leipziger Prozesse. Deutsche Kriegsverbrechen und ihre strafrechtliche Verfolgung nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg, Hamburg 2003: Hamburger Edition.

- Hankel, Gerd: The Leipzig trials. German war crimes and their legal consequences after World War I, Dordrecht 2014: Republic of Letters Publishing.

- Mullins, Claud: The Leipzig trials. An account of the war criminals' trials and a study of German mentality, London 1921: H.F. & G. Witherby.

- Wiggenhorn, Harald: Verliererjustiz. Die Leipziger Kriegsverbrecherprozesse nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg, Baden-Baden 2005: Nomos.