Military Intelligence before 1914↑

The organization of Sektion IIIb in 1889 constituted the beginning of a permanent military intelligence gathering process in the Prussian-German army. Its focus was on France and Russia. Great Britain was covered by the navy’s intelligence branch. While IIIb was responsible for the collection of intelligence alone, its assessment was done by several sections with regional responsibilities in the general staff. Its major interest was in mobilization plans, orders of battle, and technical intelligence on railroads, fortresses, and new weapons. Its means were mainly open source intelligence (OSINT), concealed reconnaissance trips by active or retired officers, the reporting of military attachés, and – to a much lesser degree than generally assumed – spies, i.e. human intelligence (HUMINT). The installation of permanent intelligence posts, the Nachrichtenoffiziere, along the borders in 1907 was a first step towards a modern intelligence organization. With a strong federal law enforcement tradition in Germany, a notorious lack of funding, a general low regard for intelligence in the army, and two well-established intelligence organizations in France and Russia, IIIb faced a complicated task.

Intelligence and the Changing Character of War, 1914-1918↑

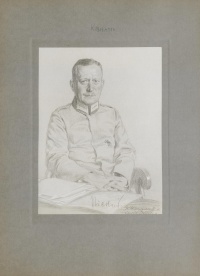

During the war, IIIb was headed by Walter Nicolai (1873-1947), who was given leave at the end of the war as a lieutenant colonel. The changing character of the conflict from a war of maneuver to a positional war initiated a fundamental restructuring of the intelligence process and its institutions. The assessment sections of the general staff converted into the Nachrichtenabteilung (not to be confused with IIIb and renamed Fremde Heere in 1917). Sektion IIIb itself was upgraded to a full section (Abteilung IIIb) in June 1915.

With regard to the intelligence disciplines, the war resulted in the dwindling significance of OSINT, a reorientation of HUMINT from classic spies to the organized interrogation of prisoners of war, and the rise of technology, particularly aerial photography and signal intelligence. Covert action and operational deception were two further fields of IIIb’s activities from as early as 1916.

The biggest challenge was arguably the organization of counter intelligence in the vast occupied territories of Belgium, France, Luxembourg, and Russia. Here, IIIb and the army’s executive arm, the Geheime Feldpolizei (Secret Field Police), fought several Allied espionage networks. IIIb had also rather accidentally taken on press and postal censorship at the beginning of the war; here its involvement was ill-conceived and inexpedient.

Domestic tasks remained a permanent source of conflict and needed steady coordination with the Prussian War Ministry (here Oberzensurstelle and Kriegspresseamt), the High Command’s section for foreign military propaganda (Militärische Stelle des Auswärtigen Amtes and Bild- und Filmamt), and the mighty territorial commanders (Militärbefehlshaber). Confronted with this heterogeneous portfolio, Nicolai began to delegate intelligence matters to subordinates in order to concentrate on propaganda efforts. The year 1917 saw the introduction of the Vaterländische Unterricht (Patriotic Instructions), a propaganda scheme targeting increasing war-weariness within Germany.

Conclusion↑

An assessment of Abteilung IIIb remains ambiguous: under difficult war conditions, the section managed to develop a modern all-source intelligence system from scratch. With its operational focus on France and Russia, it was successful before and during the war against these major enemies. Nevertheless, this focus meant that the global dimension of the war could hardly be understood by IIIb’s one and only intelligence consumer, the general staff. Furthermore, in the absence of an established civilian apparatus for domestic security and propaganda, the general staff assigned these tasks to IIIb for which the institution was neither trained nor suited. Even under the conditions of total war, Imperial Germany refrained from organizing a secret police and its approaches to propaganda remained comparatively late and traditionalist. It is therefore not surprising that IIIb’s performance in these two fields was taken as a negative blueprint by the National Socialist government from 1933 onwards.

Markus Pöhlmann, Zentrum für Militärgeschichte und Sozialwissenschaften der Bundeswehr

Section Editor: Christoph Nübel

Selected Bibliography

- Altenhöner, Florian: Kommunikation und Kontrolle. Gerüchte und städtische Öffentlichkeiten in Berlin und London 1914/1918, Munich 2008: Oldenbourg.

- Boghardt, Thomas: Spies of the Kaiser. German covert operations in Great Britain during the First World War era, Baskingstoke 2004: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Deist, Wilhelm: Zensur und Propaganda in Deutschland während des Ersten Weltkrieges, in: Deist, Wilhelm (ed.): Militär, Staat und Gesellschaft. Studien zur preußisch-deutschen Militärgeschichte, Munich 1991: De Gruyter, pp. 153-163.

- Koch, Christian: Giftpfeile über der Front: Flugschriftpropaganda im und nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg, Essen 2015: Klartext.

- Pöhlmann, Markus: German intelligence at war, in: Journal of Intelligence History 5/2, 2005, pp. 25-54.

- Schmidt, Jürgen W.: Gegen Russland und Frankreich: der deutsche militärische Geheimdienst 1890-1914, Ludwigsfelde 2006: Ludwigsfelder Verlagshaus.