Introduction↑

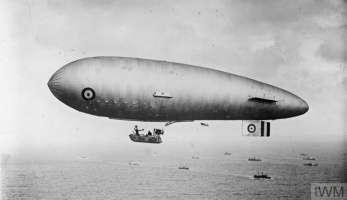

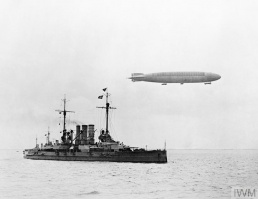

Zeppelins illustrated air power’s strategic potential, introducing systematic strategic bombing and negating geographic barriers like the English Channel. When the war began, Germany, France, Britain, Italy, and Russia acquired airships for reconnaissance. Most were pressure airships, which used the hull envelope to contain the gas. Zeppelins were large, long-range airships with a metal frame. They were a symbol of German pride even before the war. Graf Ferdinand von Zeppelin (1838-1917) launched his first successful airship in 1900. Germany was the first to employ them as a strategic weapon, though initially the Imperial German Navy envisioned Zeppelins as scouts for the fleet, while the German army employed them for reconnaissance. The Royal Naval Air Service successfully used airships for maritime surveillance and anti-submarine reconnaissance. Airships of all types were vulnerable to severe weather.

Early Use and Description↑

Early attempts to use airships as tactical weapons were unsuccessful since they were inaccurate and exposed to artillery and small arms fire from the ground, which caused some losses. The first German military Zeppelin attack was by an army Zeppelin against Liège, Belgium in August 1914, indiscriminately killing and injuring civilians, but the airship crashed due to battle damage. With their long range, Zeppelins could cross the English Channel and penetrate deep into enemy territory. Later attacks, therefore, were directed against France and Britain.

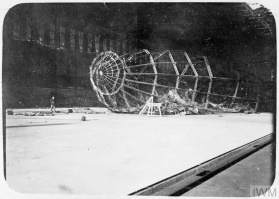

A typical German Zeppelin was over 150 meters long with a diameter over 18.5 meters and had a volume of over 28,300 cubic meters of hydrogen gas contained in 19 individual bags. Powered by three, four, or six motors depending on the class, they cruised at about 65 kph with a top speed of almost 100 kph. Their initial service ceiling was about 3,500 meters, but later models reached almost 6,000 meters. They carried a crew of nineteen to twenty-one aviators. Armaments included seven or eight machine guns and approximately 1,800 kg of high explosive and incendiary bombs.

↑

While the army wanted to attack Britain in a “frightfulness” policy – or Schrecklichkeit – to cow civilian populations, the navy saw strategic aerial bombing as part of an overall combined arms strategy to complement submarine warfare. Submarines would interdict maritime supplies and retaliate against the Royal Navy’s blockade, while strategic bombing took the war to the enemy and disrupted the war effort. Although civilian factories and cities were bombed, the navy saw this as a more legitimate form of warfare than starving the innocent German women and children who were the indiscriminate targets of the British blockade. This campaign heralded 20th century ideas of total war and forever changed the nature of warfare.

The first navy attacks on Britain occurred on the night of 19-20 January 1915, when two German navy Zeppelins bombed Yarmouth and King's Lynn. Both airships returned to base safely, having killed four and injured sixteen people. Although the attacks were somewhat destructive, the incendiary bombs did not cause any great fires. The technology was rudimentary and the bombs sometimes did not ignite, but they burned fiercely when they did. Aiming was crude and high explosive bombs often missed their targets. Even on good days, successful bombing missions were difficult to accomplish.

↑

German naval strategy ultimately centered on a bombing campaign against London. The first successful Zeppelin attack on London was carried out by a military airship, LZ 38, in May 1915. Afterwards, naval airships began their onslaught. A frequent and distinct target were the Thames docks at the East End. Zeppelins attacked with impunity. Initially, Britain’s defenses were inadequate against them, even though the Zeppelins were slow moving. Despite poor bombing accuracy and great difficulty navigating and fixing position, Zeppelins were somewhat destructive. Their attacks caused terror and work stoppages in war factories. Zeppelins were also effective reconnaissance platforms, assisting the Germans in photographing important targets in their enemy’s homeland. While German airships flew over Britain’s midlands and surveyed the enemy, Britain had no comparable capability against Germany.

On 8 September 1915, Zeppelins started numerous London fires and destroyed about £500,000 worth of property. By January 1916, they had made twenty-one raids, dropped 1,900 bombs totaling over 32,000 kg, killed 277, and wounded 645. The damage caused by these attacks was estimated at £870,000. By 1918, Zeppelin attacks had killed some 557 people and injured 1,358, a total of 1,915 casualties. They were virtually unstoppable until 6 June 1916, when the British developed a rudimentary air defense system that was the precursor to the system used in World War II, including twelve air defense squadrons scattered over thirty aerodromes across Britain.

British Air Defense↑

The British created a reliable warning network based on sound detection and ranging. They established rings of observers, searchlights, and anti-aircraft guns in belts around the capital. They produced more night-fighting pilots, anti-aircraft guns, and shells; and they developed better night-fighting pursuit aircraft equipped with luminous instruments, an upward-canted Lewis gun, and efficient incendiary and explosive bullets that could ignite the hydrogen gas and bring the Zeppelins down in flames. Twelve pursuit squadrons with 110 aircraft around London were dedicated to air defense.

Although German Zeppelins at last began to fall to British aircraft, some German airmen thought more Zeppelin attacks might pressure the British government to the point of collapse. The navy’s prominent airship commander, Peter Strasser (1876-1918), pressed for the new “V” class Zeppelin that could reach heights of 4,800-6,000 meters. After massive Allied casualties at Verdun and the Somme in 1916, there were shakeups in both British and French leadership. David Lloyd George (1863-1945) cobbled together a coalition government which seemed weak to German eyes. Russia collapsed in 1917 and the Germans reinvigorated the Western Front with at least a million hardened combat veterans from the east. German leaders hoped that unrestricted submarine warfare in an all-out land, sea, and air effort might strangle Britain before the unprepared United States could make an impact on the war.

Zeppelin Losses and Impact on Air War↑

Naval airship attacks continued until 1917, but the British slowly gained the upper hand and German losses were high. 66 percent, or seventy-seven out of 115 German Zeppelins in the war, were shot down or disabled. The Imperial German Staff therefore turned to airplanes, such as the “giant” and Gotha bombers, which could attack both in the day and in the night.

Nevertheless, Zeppelins were the harbinger of systematic strategic bombing, negating geographic barriers like the English Channel. When Germany surrendered without being invaded, airmen and politicians envisioned a new potential. Strategic bombing became the foundation for air power theories and the raison d’être of air forces between the wars. Finally, Zeppelins in the Great War helped introduce the doctrine that air power is inherently strategic, a doctrine accepted virtually without question.

Charles Dusch, United States Air Force Academy

Section Editor: Mark E. Grotelueschen

Selected Bibliography

- Collier, Basil: The airship. A history, New York 1974: Putnam.

- Fredette, Raymond H.: The sky on fire. The first battle of Britain, 1917-1918, Tuscaloosa 2014: University of Alabama Press.

- Morris, Joseph: The German air raids on Great Britain, 1914-1918, London 1925: S. Low, Marston & Co.

- Morrow, Jr., John Howard: The Great War in the air. Military aviation from 1909 to 1921, Washington, D.C. 1993: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Murray, Williamson: War in the air, 1914-1945, London 2002: Cassell.

- Strachan, Hew: The First World War, New York 2003: Viking.

- Syon, Guillaume de: Zeppelin!: Germany and the airship, 1900-1939, Baltimore; London 2007: Johns Hopkins University Press.