Introduction↑

Graffiti served several purposes ranging from enthusiasm for the war to subversion and the registering of survival. As a medium, it was used by officers near the front line and by mutinying troops, signifying the survival of the individual and offering a place to comment on authority. The variety and amount of graffiti indicate that it should be considered part of the linguistic legacy of the conflict.

The Illustrated War News of 18 April 1917 showed two photographs of Allied troops in recaptured French villages posing beneath the words “Gott strafe England” (God punish England) painted on walls and wooden doors. Germans were outraged at Britain for entering the war.

Official Graffiti↑

The official use of the format of graffiti solved a pragmatic need for signage as part of the logistics of war. This might take the form of signage such as “Watercarts 2” or “D Company Kitchen”, the familiar “Hommes 40, chevaux 8” (40 men or 8 horses) on the sides of transport train-carriages, or the German words “gute Leute” (good people) chalked on the doors of Belgian houses where a white flag had been flown. It was complemented by refugees’ chalked messages which told searching relations and friends where they had gone.

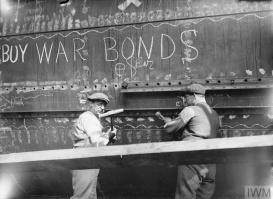

The Train Carriage as Canvas↑

Train carriages were used by German and Allied troops leaving for the front in 1914 as physical surfaces for graffiti-writing. Slogans and cartoons were chalked on the outside of the carriages. During the 1917 French mutinies, the trains which symbolised the headquarters’ power over the poilu’s access to home became the surface on which the soldiers’ grievances were broadcast to the world. In 1914, chalked graffiti were allowed to remain on French train carriages, normalising them as linguistic culture, as challenges to the Kaiser, as well as celebrations of identity. This continued throughout the 1917 mutinies.

Bravado↑

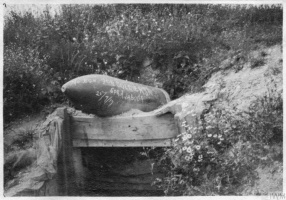

Just as pre-war suffragettes had chalked their slogans on walls, artillery gunners often chalked taunting messages on shells, possibly sometimes set up for press photographers. The words “Bon Sonty” (Tommy-French for bon santé – good health) were sometimes chalked on shells; Edmund Blunden (1896-1974) preferred ironic wit to monotonous jokes about the German royal family. Guns were daubed with names, with Kate Finzi (1890-1958) documenting “Homeless Hector” and “Weary Willie”, in November 1914.

Subversion and Identity↑

The anonymity of graffiti made it possible to ridicule the pomposity of authority. The Australian slogan “Foo was here”, with its cartoon of a long-nosed face peering over a wall, applied to railway carriages and camp walls, and re-appearing twenty years later, made fun of the intended orderliness of army life. Words scrawled on monuments served as an indicator of the degradation of war, but also the persistent survival of identity amid the ruins. The caves at Arras show the names of tunnelers, but those at Naours display those of soldier-sightseers, a reminder of graffiti’s anti-authoritarian attitude. Yet soldiers’ graffiti was itself seen immediately post-war as a memorial, visitors to the Grange Tunnel under Vimy Ridge being asked not to add their names to the walls.

Graffiti as Part of the Linguistic Reaction to and Legacy of the War↑

British troops entering Péronne in March 1917 found a large wooden sign bearing the words of Johann Goethe (1749-1832) “Nicht ärgern, nur wundern!” (Don’t be outraged, just amazed!) on the remains of the Hôtel de Ville. Interpretations vary as to whether this expressed German outrage at British artillery, a comment to the newly occupying troops on the level of chaos, or just amazement at the degree of the war’s destructive power.

Graffiti was part of the linguistic legacy of a war whose creativity was overwhelmingly verbal, meeting a need to leave an expression intended to be more lasting than the spoken word. Whether the aim was the survival of soldiers’ names, or, as in the case of the Péronne sign, the recognition of the effects of industrialised war, graffiti served to pass written comment on what was happening, even if only to state “I am still alive, here, now”.

Julian Walker, University College London

Section Editor: Emmanuelle Cronier

Selected Bibliography

- Brophy, John / Partridge, Eric: Songs and slang of the British soldier 1914-1918, London 1930: Eric Partridge.

- Fraser, Edward / Gibbons, John: Soldier and sailor words and phrases, London 1925: Routledge.

- Loez, André: Mots et cultures de l'indiscipline. Les graffiti des mutins de 1917, in: Genèses 59/2, 2005, pp. 25-46.

- Walker, Julian: Words and the First World War, London 2017: Bloomsbury.