Introduction↑

Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este’s (1863-1914) life has been largely overshadowed by his assassination in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914. This is unfortunate, because from personal and political perspectives it sheds important light on the Habsburg Monarchy, whose throne he was to inherit, as well as on the origins of World War I.

Youth and Personality↑

When he was born in Graz, Austria on 18 December 1863, few would have foreseen Franz Ferdinand as heir apparent. Ahead of him in line for the throne were Francis Joseph I, Emperor of Austria’s (1830-1916) son Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria (1858-1889) and brothers Maximilian, Emperor of Mexico (1833-1896) and Charles Louis, Archduke of Austria (1833-1896), the latter Franz Ferdinand’s father. But Maximilian forfeited his inheritance when he accepted the crown of Mexico; Rudolf committed suicide; and Karl Ludwig died in 1896.

Yet the emperor neglected to name his nephew as crown prince. Stricken with tuberculosis in 1895, Franz Ferdinand was so ill that the court began grooming his younger and more likable brother Otto Franz, Archduke of Austria (1865-1906) for the throne. Only in 1898, when doctors declared Franz Ferdinand disease-free, was the title conferred. It was one of many slights that the archduke never forgot, contributing to his lifelong tension with the emperor.

Franz Ferdinand’s sensitivities began in childhood. Sickly and sullen, he lacked attention from his mother, Maria Annunciata of Bourbon-Two Sicilies (1843-1871), who died of tuberculosis when he was seven, and could not compete with the flamboyant Otto, whom his father favored. The archduke’s first stroke of fortune thus came via his Portuguese stepmother, Maria Theresia, Archduchess of Austria (1855-1944). “Mama” showered him with love and lifted his self-esteem.

Franz Ferdinand’s next stroke of fortune was material in nature: he inherited the Este estate at age twelve from Francis V, Duke of Modena (1819-1875). Ironically, the bequest required he learn Italian; Franz Ferdinand became famous for his poor linguistic skills and his loathing of Italy. But it made him immensely wealthy, allowing him to pursue his passions for collecting antiquities, preserving historical sites, renovating his properties, and hunting. The latter was no mere pastime for the archduke, who recorded shooting 274,889 living creatures in his lifetime. To this day, hostile writers use his fervent hunting to ridicule his potential as monarch.

Like most Habsburg males, Franz Ferdinand entered the army early and was promoted regularly. Unlike his peers, he took a year off his duties to travel the world, from North Africa to India, East Asia, Australia, and America, where he attended the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. His published journals describe the voyage as an effort “to learn about foreign peoples, political structures, cultures, and customs through personal experience.”[1]

Marriage↑

Upon returning home, Franz Ferdinand joined a brigade in Budweis, from which he regularly visited the Pressburg (Bratislava) estate of Isabella, Archduchess of Austria (1856-1931). There he fell in love with her lady-in-waiting, Countess Sophie Chotek. Since the Choteks lacked the proper noble lineage to marry into the Habsburg family – according to the Austrian schedule of nobility, the Choteks did not belong to a ruling or formerly ruling house – they kept their relationship secret. Sophie’s letters sustained Franz Ferdinand during his long convalescence. What also fortified him was the overt pleasure some Hungarian papers took in his expected death. As a young officer in Ödenburg (Sopron), the archduke had been so angered by the nationalism of his Hungarian men that he lashed out publicly, thus sowing a severe rift with his country’s second most populous nation.

These experiences – his will to live despite his antagonists and his irrepressible love for the "unequal" countess – were formative in shaping Franz Ferdinand’s character. The struggle he waged to marry Sophie Chotek cost him the court’s favor and all inheritance rights for his future children, which he renounced in a debasing ceremony before the Habsburg hierarchy. The humiliations mounted, as protocol forbade Sophie, Archduchess of Austria (1868-1914) from appearing beside her husband at official functions.

Public Sphere and Politics↑

Yet Franz Ferdinand’s devotion to his wife and children – Princess Sophie of Hohenberg (1901-1990), Maximilian, Duke of Hohenberg (1902-1962), and Prince Ernst of Hohenberg (1904-1954) – was irreproachable. Even his bitterest enemies admired his family life. The public sphere was another story. The archduke has been described as haughty, acerbic, and insufferable. “He could either love or hate,” wrote Ottokar Graf Czernin (1872-1932), and his hatred was legion, including Hungarians, socialists, Freemasons, and Jews.[2] A devout Catholic close to Vienna Mayor Karl Lueger’s (1844-1910) anti-Semitic Christian Social Party and an ultraconservative opposed to universal manhood suffrage, Franz Ferdinand seemed to many to be so out of step with the increasingly secular and democratic age that his reign would have destroyed the fragile dual monarchy.

Herein lies a key question for historiography surrounding Franz Ferdinand: How would he have reformed the empire’s political structure in an effort to prevent national dissolution? The archduke well understood the multinational empire’s need for reform. Indeed in his “Program for the Change of Dynasty,” he modeled himself on Francis I, Emperor of Austria (1768-1835), who reconsolidated the regime after Emperor Napoleon I, Emperor of the French’s (1769-1821) dismemberment. Yet while he flirted with trialism (converting the dualist state into a three-pronged Austro-Hungarian-South Slav state) and other forms of federalism, the archduke never settled on a specific program. And his plan to increase the power of Slavs (nearly half the empire’s inhabitants) at the expense of Hungarians (and with force if need be) only added to the anxiety over his reign. Scholars, like contemporaries, are divided over whether the heir had the personal and political skills to hold the empire together.

The archduke’s foreign policy followed from his concern for the empire’s internal weaknesses. Foremost, he believed peace was essential to preserving the monarchy. In this respect, the Russophilic Franz Ferdinand worked to strengthen Austro-Russian relations, even hoping to restore the Three Emperor’s League. With Francis Joseph’s authorization of a military chancellery in 1906 and its elevation to official status two years later, the archduke gained greater access to foreign affairs and influence over governance. In 1912, he secured Franz Xaver Josef Conrad von Hötzendorf’s (1852-1925) reappointment as chief of the general staff due to the threat of war with Serbia, whose irredentism aimed to destroy Austria-Hungary by luring its South Slavs into “Greater Serbia.” Yet Conrad’s repeated pleas for “preventive war” worried Franz Ferdinand, who wished to avoid military conflict until the monarchy could be stabilized through political reform. As scholars note, the archduke’s death removed the one voice that would have spoken out forcefully against war with Serbia during the July Crisis.

Yet Franz Ferdinand was neither politically inflexible nor a pacifist. He labored lifelong to strengthen the army and navy, and in the First Balkan War saw an opening for intervention against Serbia which, with hindsight, appears highly astute, especially as it was predicated on prior agreement with Russia and German support. The latter was not forthcoming, though that and his anti-Prussian upbringing did not prevent Franz Ferdinand from drawing closer to Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) through mutual personal and foreign policy interests, not to mention the Kaiser’s respectful reception of Sophie Chotek. His animosity towards Britain also softened through personal visits with his wife to the royal court – in May 1912, when they traveled incognito; and in late 1913, when the archduke and Sophie were private guests of George V, King of Great Britain (1865-1936) at Windsor Castle.

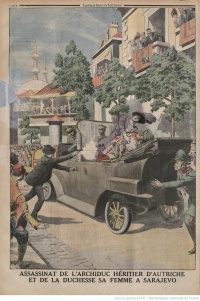

Sarajevo Assassination and Legacy↑

The Bosnia trip was another military undertaking for the war-wary Franz Ferdinand. As inspector general of Austria-Hungary’s armed forces, he reluctantly went south in mid-summer in order to observe annual maneuvers. An incentive for the trip may also have been the rare chance to be seen publicly in the empire with his morganatic wife. Despite many warnings, the dutiful archduke proceeded with the last day’s ceremonial procession through the Bosnian capital to please his host, Governor-General Oscar Potiorek (1853-1933). He instead died on Potiorek’s sofa, shot through the neck by the Bosnian student Gavrilo Princip (1894-1918).

It is a tragic irony that the war Franz Ferdinand strived to prevent and the collapse of the empire he lived to reform resulted from decisions made directly in response to his death. Yet more tragic is that this “man of stature,” as the historian Robert Kann (1906-1981) called him, was hastily buried at his Artstetten palace, where had built a crypt for himself and Sophie, since her lesser status prevented her from being interred beside him in the Kaiser Crypt. Henceforth, he was largely forgotten in Austria, where to this day there is not a single “Franz Ferdinand” street or square outside of Artstetten. Or, when the archduke is remembered – as with a memorial plaque placed in the Kaiser Crypt in 1986 – it is as the “first victim of the First World War,” rather than as one of the most politically engaged successors in the long history of the Habsburg Empire.[3]

Paul Miller, McDaniel College

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Notes

- ↑ Franz Ferdinand (Archduke of Austria): Tagebuch meiner Reise um die Erde. 1892-1893, Erster Band, Vienna 1895, p. viii. See also: Gerbert, Frank (ed.): Franz Ferdinand von Österreich-Este. Die Eingeborenen machten keinen besonders günstigen Eindruck. Tagebuch meiner Reise um die Erde 1892-1893, Vienna 2013, p. 20.

- ↑ Czernin, Ottokar: Im Weltkriege, Berlin et al. 1919, p. 46.

- ↑ Kann, Robert: A History of the Habsburg Empire. 1526-1918, Berkeley 1974, p. 418.

Selected Bibliography

- Aichelburg, Wladimir: Erzherzog Franz Ferdinand von Österreich-Este 1863-1914. Notizen zu einem ungewöhnlichen Tagebuch eines außergewöhnlichen Lebens, 3 volumes, Horn 2014: Ferdinand Berger und Söhne.

- Bled, Jean-Paul: Franz Ferdinand. Der eigensinnige Thronfolger, Vienna 2013: Böhlau.

- Hannig, Alma: Franz Ferdinand. Die Biografie, Vienna 2013: Amalthea.

- Kann, Robert A.: Erzherzog Franz Ferdinand Studien, Munich 1976: Oldenbourg.

- Kronenbitter, Günther: Haus ohne Macht? Erzherzog Franz Ferdinand (1863–1914) und die Krise der Habsburgmonarchie, in: Weber, Wolfgang (ed.): Der Fürst. Ideen und Wirklichkeiten in der europäischen Geschichte, Cologne 1998: Böhlau, pp. 169-208.