Early Career↑

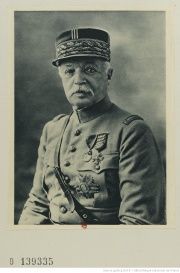

Marie-Émile Fayolle (1852-1928) was one of the best senior field commanders to emerge from the challenging military environment of the Western Front. Beginning the war as a reserve division commander, by its end he was commanding France’s principal offensive army group in the advance to victory, and afterwards he would be made a marshal of France.

An artillery officer who studied at École polytechnique, Fayolle taught the course in artillery tactics at France’s École supérieure de guerre before the war, alongside Ferdinand Foch (1851-1929) and Philippe Pétain (1856-1951). Retired shortly before hostilities broke out, he took command of a reserve division in the defensive battles in Lorraine in August 1914, in which he quickly grasped the challenges that faced armies on the industrialized battlefield: “I will attack with the greatest care, with all the artillery and the fewest infantry necessary.”[1] His wartime diary, from which this quotation is taken, gives deep insight into both its author’s personality and the nature of his command during the war.

Fayolle’s 70th Division fought in the Second Battle of Artois in May-June 1915, as part of Pétain’s XXXIII Army Corps, capturing Ablain-St-Nazaire and Carency. Fayolle succeeded Pétain in command of this corps which he led in the Third Battle of Artois in September 1915. These battles showed him the problems of trench warfare, and pointed towards tentative solutions:

he wrote in January 1916.

Promoted to army command, he led the Sixth Army throughout the 1916 Somme offensive, applying Foch’s “scientific” offensive method developed in the Artois battles – successive carefully organised, firepower-intensive, limited attacks – to advance steadily through the German defensive positions with an acceptable rate of casualties. Nonetheless, since the Somme did not prove decisive, he was moved to an inferior army command, First Army, when Robert Nivelle (1856-1924) replaced Joseph Joffre (1852-1931) as commander-in-chief in December 1916. As he noted, Nivelle’s protégé Charles Mangin (1866-1925), who took over his successful Sixth Army, had merely reconfigured the methods of the Somme at Verdun.

Army Group Commander↑

After the failure of Nivelle’s over-ambitious offensive, Fayolle was rehabilitated, promoted to army group command and put in charge of managing the messy attritional battle around Reims that was one legacy of Nivelle’s misadventure. Fayolle had been considered as Nivelle’s replacement, although he did not regret the fact that Pétain was chosen. Henry Bordeaux (1870-1963), later his biographer, painted a pen-portrait as he assumed this new responsibility:

He contributed to the restoration of morale in an army beset by mutinies in late spring, not least through supervising the Second Army’s Second Battle of Verdun (20-26 August 1917), in which the high ground west of the fortress was stormed.

In October 1917, when the Italian Second Army was smashed in the Battle of Caporetto, Fayolle was given command of the French forces dispatched to Italy, in the expectation that he might have to take charge of running that battle. In the event, his role became one of retraining the Italian army and mentoring its new commander-in-chief, Armando Diaz (1861-1928). Diaz proved a good pupil – “you are my experienced senior” he confided to Fayolle at one point[4] – and his army was restored to fighting fitness over the winter.

Called back to the Western Front in February 1918 in anticipation of a German offensive, Fayolle was given responsibility for engaging and containing the “Operation Michael” attack at the end of March. Placing his faith in God – he was a devout Catholic – and reengaging in battle with relish, he committed the armies under his direction to closing the gap that had opened between the French and British armies south of the river Somme, thereby blocking the German thrust towards Amiens. In a later phase of the defensive battle he supervised the counterattack in the June Battle of the Matz – on this occasion Mangin was his principal subordinate.

In the advance to victory, Fayolle’s Reserve Army Group was in the vanguard. Beginning with the Battle of Montdidier (9-11 August – the French extension of the better known Battle of Amiens) the armies under his direction struck repeated, limited but effective blows that seized the southern extension of the Hindenburg Line and pursued the enemy to the French frontier by the armistice. Fayolle did not always see eye-to-eye with his superiors, Foch and Pétain, whom he felt interfered too much in his conduct of operations and then took credit when they were successful. But they both saw him as a dependable and effective subordinate who could be entrusted with the most difficult tasks on the battlefield.

After the War↑

Following the armistice Fayolle was given command of the French army of occupation in Germany, and belatedly, after a lively press campaign, was made a marshal of France like the other victorious Western Front leaders, Foch and Pétain, in 1921. After his death in 1928 he was laid to rest with other French military heroes in the crypt at Les Invalides.

A soldiers’ general who was solicitous for the welfare of his troops and distraught when they suffered heavy casualties, he strove to avoid this by meticulous preparation. He took a hands-on approach to operational planning, studying the ground and intelligence picture carefully and personally drafting his army’s plan of operations before fine-tuning it with his staff. As Duval attested, “he was a true man of war who grew on the battlefield.”[5]

William Philpott, King's College London

Section Editor: Emmanuelle Cronier

Notes

- ↑ 30 August 1914, in Contamine, Henry (ed.): Maréchal Fayolle: Cahiers secrets de la grande guerre, Paris 1964, p. 27.

- ↑ 21 January 1916, ibid., p. 142.

- ↑ 3 May 1917, in Bordeaux, Henry: Histoire d’une vie, L’année ténébreuse, 3 janvier 1917–21 mars 1918, vol. 5, Paris 1959, p. 77.

- ↑ 2 January 1918, in Contamine, Henry (ed.): Maréchal Fayolle: Cahiers secrets de la grande guerre, Paris 1964, p. 250.

- ↑ Duval, Maurice: ‘Le Maréchal Fayolle’, in: Carnets de la sabretache: revue militaire retrospective 370 (1934), p. 227.

Selected Bibliography

- Bordeaux, Henry: Histoire d’une vie. L’année ténébreuse, volume 6, Paris 1959: Plon.

- Bordeaux, Henry: Le Maréchal Fayolle, Paris 1921: Éditions G. Crés.

- Contamine, Henry (ed.): Maréchal Fayolle. Cahiers secrets de la Grande Guerre, Paris 1964: Plon.

- Duval, Maurice: Le Maréchal Fayolle, in: Carnets de la sabretache. Revue militaire retrospective 370, 1934, pp. 224-238.

- Philpott, William: Bloody victory. The sacrifice on the Somme and the making of the twentieth century, London 2009: Little, Brown.