Introduction↑

This article explores a different aspect of New Zealand’s Great War: the experiences of soldiers on leave in Europe. It takes them, as their leave would, out of the trenches of Western Front, out of the rigors of camp life or the boredom of a convalescent hospital and into the streets and sights of London. As the scenes change, so does the story. War, especially World War One, has become almost inextricably linked with narratives of national identity.[1] In numerous histories, the deadly shores of Gallipoli and the mud of the Western Front are not only scenes of staggering mortality but also of a kind of redemptive rebirth. Away from home, and amongst the British, it is claimed, soldiers found themselves to be something distinct: they had become New Zealanders. The proponents argue that the disappointments of British military command – even of British soldiers themselves – and the recognition that New Zealanders had distinctive characteristics provided a platform for an emerging sense of nationality. Consequently World War I has been conscripted into a larger story of a New Zealand identity formed by breaking old ties between New Zealand and the mother country.[2]

The experiences of soldiers on leave reveal another possibility. The location and scale of the war meant that an unprecedented number of New Zealanders found themselves in Britain. Soldiers also took leave elsewhere in Europe, but in much smaller numbers, and research on their experiences is minimal.[3] In contrast, leave in Britain had a specific cultural effect. This article considers the ways in which the war acted to renew and reconstruct the idea of Britain as "Home". It begins by introducing the idea of the "soldier-tourist" before examining why Britain was important to New Zealanders. It then examines the experiences of soldiers on leave, before turning to the work of voluntary organisations, such as the YMCA and the New Zealand War Contingent Association, and their role in creating Britain, and London in particular, as a "home away from home" for New Zealand soldiers.

The Soldier Tourist↑

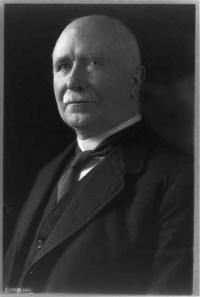

War changed the nature of travel. Before the outbreak of fighting in 1914, tourism had been limited to the leisured classes who could afford both the time and money required to travel overseas. This was particularly true of far-flung New Zealand. Even with the advent of steam travel, in 1914 Britain was still six weeks away by sea. However, by committing troops to fight in Europe, the New Zealand government not only created a civilian army but also provided a rare opportunity for New Zealanders to travel. Its impact was enormous. By the war’s end, some 100,444 New Zealanders had been sent overseas; 16,697 of them would never return home.[4] These New Zealanders were part of an even larger global mobilization that included 1.3 million troops from the ‘white’ Dominions alone.[5] Canadian and Australian soldiers thus shared many of the experiences of New Zealand soldiers.[6] Yet it was not simply the magnitude of the numbers that was new. As the government paid the fares, and as recruiting itself cut across class lines, war came to prefigure "the age of democratic tourism".[7] It was a social shift that the soldiers themselves registered: New Zealand troops sometimes called themselves "Bill Massey’s tourists", in a sardonic salute to the then Prime Minster William Massey (1856-1925).

Though it seems hard to comprehend now, the chance to be a tourist was, at least initially, part of war’s allure. It was not the only factor: patriotism, idealism, duty, even supporting your mate or brother could lead to enlistment. However, "most volunteers were motivated, said Defence Officers, by adventure, travel, curiosity and the colonial love of a fight."[8] In Australia, where conscription was never introduced, "recruiting committees were not backward in advertising enlistment as a 'Free Tour to Great Britain and Europe – the Chance of a Lifetime' [...] many men felt that enlisting was worthwhile just to see Europe."[9] As the war ground on, casualty lists made the real costs of the "free tours" clear, yet travel remained, if not an incentive, then at least a bonus, of war service. One New Zealand soldier, a veteran of Gallipoli about to return to the war, wrote:

As the itinerary of the 13th Reinforcements show, wartime travel from New Zealand offered plenty of tourism opportunities. In a letter to a friend, Jack Hunter of Masterton noted "I can now claim to be one of Bill Massey’s tourists, as I have been to Ceylon, Egypt, Italy, France and England among other places... ."[11] Travel was not restricted to that first voyage abroad: New Zealand soldiers saw active service across the globe, including in Samoa, Egypt, and Palestine. However, the vast majority served on the Western Front. For these men, and for their Australian and Canadian counterparts, England was "every loyal tourist’s preferred goal", and its principal sight was London.[12] Soldier George Knight captured the feelings of many others when he wrote from Boulogne:

New Zealand’s Cultural Ties to Britain↑

Why was Britain so important to New Zealanders? One answer is that many New Zealand soldiers were of recent British heritage. Migration to New Zealand throughout the colonial period had been almost exclusively from England and Scotland, with smaller number of Irish and Welsh settlers. It was not until the end of the 19th century that locally born New Zealanders began to outnumber migrants in the population. By 1914, many of these first generation New Zealanders would have been of recruiting age; yet they were just one generation removed, and family memories of a British "Home" were still strong. Plenty more recruits were actually migrants themselves; in 1914, one in five of the population and 30 percent of the NZEF were British-born.[14] In such cases, war really brought them home.

Yet family links were not the only reason Britain was such a goal. As one old soldier recalled in the 1980s, "you’ve got to take into consideration that this British Empire, which has gone now, which means nothing to you, was at the zenith, the peak of its power and popularity."[15] For all that the historiography of New Zealand, and for that matter, other former British settler societies, has emphasised the war’s role in forging an independent identity, many soldiers were conscious of their part in the empire.[16] Britain and especially London were at the heart of that empire, and as a result, they had a particular cultural resonance that other places did not. When it came to taking leave, that cultural power was self-evident. Paris could offer much the same entertainment as London, but soldiers voted with their feet. "Ten men went to England on leave for every one that stayed in France."[17]

It was not simply being further from the war zone, or speaking the same language, which made Britain so popular. Sentiment was stimulated by the almost constant presence of Britain in New Zealand’s political, economic and cultural life. In 1914 New Zealand’s foreign policy decisions, including being at war, were still made in the heart of the empire.[18] London was the principal market for butter, meat and wool, the mainstays of the New Zealand economy. (War would reinforce this connection. Through the wartime commandeer, the British government agreed to purchase all of New Zealand’s surplus primary produce.) London, Oxford and Cambridge remained central to New Zealand’s intellectual and high cultural worlds. British newspapers, magazines, journals and books arrived in New Zealand in great quantities.[19] This flow kept an "imagined London" alive and familiar in the minds of ordinary New Zealanders, giving them a sense of connection with a "home" 12,000 miles away.[20] No wonder a Gallipoli veteran Ernest Williams, on arriving in England claimed that "everything English bears the same air of familiarity due beyond question to the thoroughness with which her life is portrayed in her novels."[21]

New Zealand’s recent settler origins and its strong cultural, economic and political ties were a potent mix that worked to construct Britain as a familiar "Home". The shift in its military operations in 1916, from Egypt to the Western Front, would develop this sense of belonging in new ways.

Soldiers on Leave↑

Britain became the focus of leave from 1916, when New Zealand military operations moved away from the Middle East to the Western Front. Military infrastructure, from headquarters to training camps to hospitals, was now located in England, mostly in and around London. Consequently, New Zealand soldiers came to be concentrated there too. Exact numbers are not known, but despite the predominance of Gallipoli in popular memory, the majority of New Zealand’s 100,000 plus troops served on the Western Front. That meant most of them would spend time in Britain. Newly arrived reinforcements for the front – approximately 2,200 per month – were sent first to camps such as Sling, some seventy-four miles from London, and they could expect draft leave, usually for four days, before being sent to France.[22] Soldiers with "Blighty wounds" were counted lucky by their fellow soldiers and shipped across the channel for treatment. There were plenty of these: Brockenhurst Hospital had 1,600 patients at one point in 1918, and whilst convalescing, they too were entitled to leave.[23] For soldiers on active duty, there was always the possibility of leave away from the fighting, and as noted above, Britain was their destination of choice. Many had relatives to visit: all of them wanted to see London. Under these circumstances, the old "Home" began to take on a new role: it became the "New Zealander’s place of respite from the horrors of war, and as such it will always be remembered as a half-way Home, or as the undemonstrative New Zealander sometimes described it, 'A Home away from Home'."[24]

For any soldier who made it "Home", whether on leave from the fighting, on leave from hospital, or on leave from camp, London was the principal destination.[25] Captain Herbert King, part of the 2nd Otago Battalion, arrived in Sling camp on 30 October 1916, was granted four days’ draft leave, and went off to London promptly. "Leave for Friday and Saturday was granted and everyone was taken to London."[26] Realities of life in the camps – even the official records called Sling "unloved" – made London even more attractive, a "perpetual call to the exile in training."[27] The perpetual call led to perpetual leave extensions. Owen Clark "reported to the Army Police in London whilst on leave and asked for an extension of three days as some of my leave had been spoiled by a touch of the flu."[28] Some didn’t even bother with an excuse. "Came to London and had a roam around," wrote Stan Chesterton. "Viewed inside St Paul’s Cathedral. Very fine building. Due back in camp but overstayed a day or two."[29]

St Paul’s was only one of London’s famous sights that Bill Massey’s tourists flocked to see. Captain King had just two days leave for his first visit: "It is a large place as you know and one cannot see everything in two days but I did my best and had a look at the Houses of Parliament, St Paul’s, Westminster Abbey, Tower of London, Hyde Park, the Row, Serpentine etc. It is all very interesting and wants to be seen to be appreciated."[30] His list is repeated over and over again in soldiers’ diaries and letters. They both reflect and construct the idea of a "familiar" London, one that could be shared through letters and postcards with friends and family waiting for news at home.[31] Touring soldiers became masters of casual familiarity with the capital as they "roam[ed] about", "knock[ed ]about", "potter[ed ]about" and even had a "good old loaf" around the heart of the empire.[32] And their roaming was not confined to London’s history and heritage. Bill Massey’s tourists were young, mainly single men. In the New Zealand Main Body, for example, 56 percent of soldiers were under twenty-five years old, and 85 percent were under thirty.[33] To these soldiers, "city life is like champagne", and they drank it up in London’s theatres, restaurants and bars.[34] This was particularly so for those soldiers on leave from the front: "Jack and I are on leave", wrote one soldier, "and you can understand it is like fourteen days in Paradise after being over in France for 13 months, and I may tell you that we are living every hour of that 14 days."[35] Sex was, along with drunkenness and gambling, part of life on leave. Dominion soldiers were "described as strolling around London, hands in pockets, cigarettes in mouth, woman on arm", "effective bachelors for the duration".[36] Officers were not immune either, though apparently they "stuck to the West End, went to women recommended by friends and paid £5 for the night."[37]

Bill Massey’s tourists then, could be a little too familiar with the capital. When stationed in Egypt earlier in the war, officials responded to such behaviour by attempting to curb the soldiers. General Alexander Godley (1867-1957) marched men through the red-light district by day hoping that "a daylight look at the women", would put them off.[38] After rioting, Cairo was put out of bounds, an extraordinarily mild punishment given the destruction the troops caused.[39] But though Minister of Defence Sir James Allen (1855-1942) claimed he would rather "go through Egypt and all its Wazzas than go through London’s streets", New Zealand soldiers’ access to the heart of the empire was unrestricted.[40] Fear of miscegenation kept Indian soldiers gated in London, but for dominion soldiers, it was the metropolis, not them, that needed to be disciplined. Two volunteer organizations, the YMCA and the New Zealand War Contingent Association, undertook the job of domesticating London for the soldier tourist. They attempted to counterbalance the darker side of the metropolis by constructing a more "homely" version of the metropolis. Their efforts took two forms. Parts of London’s space were physically transformed into New Zealand space with clubs that recreated some of the comforts of home. At the same time, these associations attempted to resurrect some of the social and cultural controls of home. They were not always successful. Soldiers often noted the differences they felt between their real and their imagined home. But the work of voluntary organisations would serve to reinforce New Zealand’s ties with the metropolis.

Voluntary Organizations↑

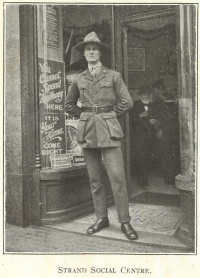

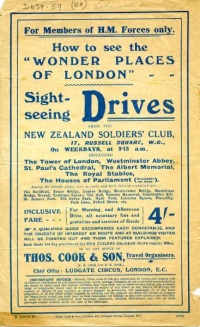

The sheer volume of soldiers on leave in London made accommodation a priority. Volunteer organizations responded by opening clubs: just one London club, the New Zealand Soldiers’ Club, recorded 67,483 bed nights in 1918 alone.[41] These clubs gave real substance to the idea of a "Home" in London, and helped form one area of London into a New Zealand neighbourhood. Clubs were clustered around Russell Square, also the location of New Zealand’s Military High Commission at 8 Southampton Row. Shakespeare Hut was in Keppel Street, on the corner of Russell Square, and the NZWCA residential club was there too, around the corner from its clubrooms in Southampton Row. They were handy to Simpson and Edwards, Colonial and Military Outfitters, at number 98 (for replacement New Zealand uniform buttons, amongst other items). It was a straight line from here to the Strand, where the High Commission was located, and the Australian YMCA hut, Aldwych (which was also popular with New Zealanders).

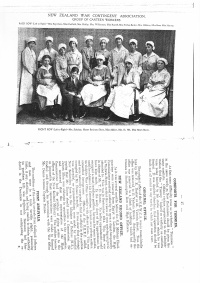

Within this neighbourhood, soldiers would find clubs fashioned as homes. In one sense, this was implicit in their function, for the clubs provided meals and accommodation. But homeliness was also reflected in the nature of contemporary volunteer work. At the turn of the century, it was women’s work; its emphasis on maternalism and domesticity leveraged women’s private roles into the public sphere.[42] War created greater scope for this work and emphasised these values. New Zealand’s soldiers’ clubs were staffed by women, often New Zealanders themselves, which increased the homelike atmosphere and acted as a reminder of family left behind in New Zealand. But these women were given a greater significance. Cooking, cleaning and helping the soldiers, they were "mothers" in the metropolis. Women at the New Zealand Soldiers’ Club were, it was claimed, "only too pleased to do anything they could for the boys in the mending and darning line."[43] Canadian social clubs worked in the same manner, offering a "'touch of home' where [...] the men could be 'cared for and mothered a bit.'"[44] Clubs were presented then as familial places, with the comforts of home and its conventions too. Within the club setting, soldiers engaged in the world’s bloodiest war became "boys", to be looked after by women who were characterised as motherly. The YMCA referred to the Shakespeare Hut as "The New Zealander’s 'Home Away from Home'", and the success of the NZWCA clubs was put down to the "homely 'atmosphere' caused by the presence of New Zealand ladies among the 'boys'".[45]

The motherly women of the clubs were positioned as moral prophylactics against London’s other, undesirable type, the prostitute. Public and military anxieties about sex and soldiers was warranted given the high rates of venereal disease amongst troops, although fear of being seen to condone immorality prevented officials from doing anything effective to prevent its spread. The New Zealand YMCA, for example, approached the problem of metropolitan temptation with a letter to soldiers warning them about London’s swarms of "hopelessly diseased women".[46] The New Zealand High Commissioner, Sir Thomas Mackenzie (1854-1930) urged the British government to segregate infected prostitutes to "preserve our men". Once again it was the city, not the soldiers, that would be disciplined. Meanwhile, at Shakespeare Hut’s canteen, the soldiers were "waited on by the lady workers in their crushed-strawberry coloured frocks... ."[47] The YMCA thought it "should have been always a comfort to the mothers, wives and sisters of the soldiers to know that such an enticing home was provided in the midst of London, with its temptations and its great loneliness".[48]

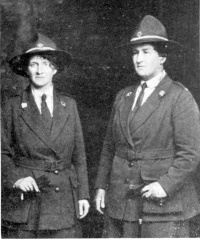

Volunteer organizations worked to create "Home" in other ways. Many soldiers had relatives to visit within Britain, adding another sense of homeliness. But the YMCA’s International Hospitality League and the NZWCA also had programmes to introduce New Zealand soldiers to the British, through dinner invitations and visits to private homes. The YMCA and NZWCA also wanted to limit access to the wrong types of homes. One technique was to intercept soldiers at train stations, to avoid "the activities of well-dressed people who meet these trains and did their utmost to induce the men to accept the hospitality of those homes, mostly dens of iniquity, which had sprung up in London".[49] The International Hospitality League was also concerned that hospitality could be carried too far. They organised street patrols, in action "between 7pm and 2am". Their work "was of a delicate personal nature requiring the utmost tact to separate men from women of known disreputable character."[50] Once again, it was the unruly London with its "disreputable" women that was to be policed. New Zealand women Adelaide Ballantine and Fanny McHugh, were members of the patrol, complete with their own uniforms and armed with sticks for "delicate" separation.[51]

Finally, historic London itself was reconstructed as a diversion from the metropolis’ darker sides. Soldiers were already interested in what they saw as their own heritage. The NZWCA and the YMCA capitalized on this, running escorted tours from their clubrooms hosted by "London gentlemen [who] acted as honorary guides and thousands of New Zealand soldiers were shown around at no cost to themselves".[52] Albert Newton was happily shepherded around: "Every day some men or ladies come here and take parties around to see the chief places of interest and pay all expenses as well. Already I have been to the Zoo, Parliament Houses, Westminster Abbey, the King’s stables, Buckingham Palace, the Royal Academy and the waxworks besides the theatre three times. It is well we have someone to guide us about as otherwise we would spend half our time looking for these places."[53] For soldiers who might have preferred some of the city’s other temptations, such tours could be difficult to avoid, as one noted: "We were walking around when a YMCA manager seized hold of us and put a guide in charge of us."[54]

Conclusion↑

A crammed four-day itinerary of churches and museums was designed to keep the soldiers away from the temptations of the metropolis, although its greatest success may have been reinforcing New Zealanders’ sense of connection to their former "home". That connection had been fostered in New Zealand, through the tight social, political, cultural, and economic connections that linked colony and metropolis together. Though war is usually considered a force in breaking those ties, the experiences of thousands of "Bill Massey’s tourists" may have strengthened some of them. For many, war brought an opportunity to experience the heart of the empire. Volunteer organisations then worked to make soldiers feel at home, especially in London. Indeed, for New Zealand soldiers on leave, Britain was as close to home as they could get.

Felicity Barnes, University of Auckland

Section Editor: Kate Hunter

Notes

- ↑ Phillips, Jock / Boyack, Nicholas / Malone, E.P. (eds): The Great Adventure. New Zealand Soldiers Describe the First World War, Wellington 1988, p. 2.

- ↑ Notably Sinclair, Keith: A Destiny Apart. New Zealand’s Search for National Identity, Wellington 1986, pp.170ff; see also Phillips / Boyack / Malone, Great Adventure 1988, p. 9; Harper, Glynn: Images of War. World War One. A Photographic Record of New Zealanders at War 1914-1918, New Zealand 2008, p. 14.

- ↑ See Tolerton, Jane: Ettie. A Life of Ettie Rout, Auckland 1992; Boyack, Nicholas: Behind the Lines. The Lives of New Zealand Soldiers in the First World War, Wellington 1989 for some detail.

- ↑ Boyack, Behind the Lines 1989, p. 8.

- ↑ Barnes, Felicity: New Zealand’s London. A Colony and its Metropolis, Auckland 2012, p. 53.

- ↑ For Australia see Gerster, Robin / Peter Pierce: On the Warpath. An Anthology of Australian Military Travel, Melbourne 2006, pp. 67-71; White, Richard: The Soldier as Tourist. The Australian Experience of the Great War, in: War and Society 5/1 (1987), pp. 63-77. For Canada, see Cozzi, Sarah: Killing Time. The Experiences of Canadian Expeditionary Force Soldiers on Leave in Britain, 1914-1918, MA Thesis, University of Ottawa, 2009.

- ↑ White, Soldier as Tourist 1987, p. 65.

- ↑ Baker, Paul: When King and Country Call. New Zealanders, Conscription and the Great War, Auckland 1988, p. 17.

- ↑ Forrest, Alison: Milling Around Outside the Town Hall. Motivation for Enlistment of the First AIF, in: Melbourne Historical Journal 18 (1987), p. 107.

- ↑ Auckland War Memorial Museum and Library (AWMML): W.H. Johns Papers, 18 January 1917, MS 1392.

- ↑ Wairarapa Daily Times, 8 January 1919, p. 4.

- ↑ White, Soldier as Tourist 1987, p. 67. For Canada see Cozzi, Killing Time 2009, pp. 118-129.

- ↑ Croad, Nancy (ed.): My Dear Home, Auckland 1995, p. 92.

- ↑ McGibbon, Ian: The Shaping of New Zealand’s War Effort, August – October 1914, in: Crawford, John / McGibbon Ian (eds.): New Zealand’s Great War. New Zealand, the Allies and the First World War, Auckland 2007, p. 51; Inwood, Kris / Oxley, Les / Roberts, Evan: Physical Stature in Nineteenth-Century New Zealand. A Preliminary Interpretation, in: Australian Economic History Review 50/3 (November 2010), p. 271.

- ↑ Boyack, Nicholas / Tolerton, Jane: In the Shadow of War. New Zealand Soldiers Talk about World War One and Their Lives, Auckland 1990, p. 25.

- ↑ Worthy, Scott: A Debt of Honour. New Zealanders' First Anzac Days, in: New Zealand Journal of History 36/2 (2002), p. 186; Belich, James: Paradise Reforged. A History of the New Zealanders from the 1880s to the year 2000, Auckland 2001, pp. 104f; Rabel, Roberto: New Zealand’s Wars, in: Byrnes, G. (ed.): New Oxford History of New Zealand, South Melbourne 2009, pp. 254f.

- ↑ Tolerton, Ettie 1992, p. 170.

- ↑ Though at war through its status in the empire, New Zealand retained the right to determine the nature of its participation.

- ↑ James Belich has described this process more broadly as ‘recolonisation’. See Belich, Paradise Reforged 2001.

- ↑ Barnes, New Zealand’s London 2012, pp. 22-31.

- ↑ Williams, E. P.: A New Zealander’s Diary, Gallipoli and France, 1915–1917, Christchurch 1998 [1924], p. 180.

- ↑ Crawford, John: ‘New Zealand is Being Bled to Death.’ The Formation, Operations and Disbandment of the Fourth Brigade, in: Crawford / McGibbon, New Zealand‘s Great War 2007, p. 252.

- ↑ Boyack/Tolerton, In the Shadow of War 1990, p. 21.

- ↑ Drew, H. T. B.: The War Effort of New Zealand. A Popular History of A) Minor Campaigns in which New Zealanders Took Part B) Services Not Fully Dealt With in the Campaign Volumes C) the Work at the Bases, Auckland 1923, p. 274.

- ↑ Ingram, N. M.: ANZAC Diary. A Nonentity in Khaki, Sydney n.d., p. 82.

- ↑ AWMML: King to Slodel 30 November 1916, Daisy Slodel Papers, MS 2002/108.

- ↑ Drew, The War Effort 1923, p. 249.

- ↑ AWMML: Owen Clark correspondence, 9 August 1918, Hugh R. Clark Papers, MS 1615.

- ↑ AWMML: Stan Chester ‘A Brief Diary of My Travels as a Member of the NZEF’, 28 December 1918, Stan Chester Papers, MS 1046.

- ↑ AWMML: King to Slodel, 13 November 1916, Daisy Slodel Papers, MS 2002/108.

- ↑ Barnes, New Zealand’s London 2012, p. 18.

- ↑ AWMML: 9 October 1918, ‘The Great Adventure’ – the Diaries and Correspondence of 48548 Private James Mackenzie, 1917–19, Embellished with Historical Context by Alan W. Hughes, 1988, James Mackenzie Papers, MS 1701; AWMML: Stan Chester, 14 March 1918, Stan Chester Papers, MS 1046; AWMML: R. A. Stables Diary, 27 April 1917, Hugh R. Clark Papers MS 1615; AWMML: 10 October 1918, James Mackenzie Papers, MS 1701.

- ↑ Phillips, Jock: A Man’s Country? The Image of the Pakeha Male – A History, Auckland 1996, p. 161.

- ↑ Ingram, ANZAC Diary n.d., p. 82.

- ↑ AWMML: Tommy to Sophia Gill, 9 January 1918, Henry Herbert Gill Papers, MS 1130.

- ↑ Levine, Philippa: Battle Colours. Race, Sex and Colonial Soldiery in World War One, in: Journal of Women’s History 9/4 (2003), p. 111.

- ↑ Tolerton, Ettie 1992, p. 155.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 124.

- ↑ Boyack, Behind the Lines 1989, p. 29.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 141.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 189.

- ↑ See Woollacott, Angela: From Moral to Professional Authority. Secularism, Social Work and Middle-class Women’s Self-construction in World War I Britain, in: Journal of Women’s History 10/2 (1998), pp. 85-112; Pickles, Katie: A Link in ‘The Great Chain of Empire Friendship’. The Victoria League in New Zealand, in: Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 33/1 (2005), pp. 29-50; Oppenheimer, Melanie: ‘The Best P.M. for the Empire in War?’ Lady Helen Munro Ferguson and the Australian Red Cross Society, 1914–1920, in: Australian Historical Studies 119 (2002), pp. 108-124.

- ↑ Chronicles of the N.Z.E.F.: 27 March 1918, p. 88.

- ↑ LAC, RG9, III, Dl, Vol. 4719, Folder 115, File 27, King George and Queen Mary Maple Leaf Club Lady's Pictorial (1 April 1916), quoted in Cozzi, Killing Time 2009, p. 55.

- ↑ Triangle Trail, 16 February 1918, p. 5; Drew, War Effort of New Zealand 1923, p. 188.

- ↑ Letter, Blighty: With the Compliments of the NZ YMCA, London 1916.

- ↑ Triangle Trail: 16 February 1918, p. 5.

- ↑ Drew, War Effort of New Zealand 1923, p. 189.

- ↑ Raymond, I. R.: New Zealanders in Mufti, 1914-1918, London 1924, p. 23.

- ↑ Buckshee: A Pictorial Record of the Work of the NZ YMCA on Active Service, London 1919, p. 66. For patrols in the context of women’s policing, see Levine, Philippa: ‘Walking the Streets in a Way No Decent Woman Should.’ Women Police in World War I, in: Journal of Modern History 66 (1994), pp. 34-78; for gender roles in WWI, see Woollacott, Angela: ‘Khaki fever’ and its Control. Gender Class Age and Morality on the British Homefront in the First World War, in: Journal of Contemporary History 29/2 (1994), pp. 325-347.

- ↑ Kai Tiaki, in: The Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand 13/1 (January 1920), p. 5.

- ↑ Buckshee, A Pictorial Record 1919, p. 61.

- ↑ AWMML: E. W. Newton to Father, Mother, Brother, 13 May 1916, A. J. and E. W. Newton Papers, MS 921.

- ↑ Harper, Barbara: Letters from Gunner 7/516 and Gunner 7/517, Wellington 1978, p. 79.

Selected Bibliography

- Barnes, Felicity: New Zealand's London. A colony and its metropolis, Auckland 2012: Auckland University Press.

- Belich, James: Paradise reforged. A history of the New Zealanders from the 1880s to the year 2000, Auckland 2002: Penguin UK.

- Boyack, Nicholas: Behind the lines. The lives of New Zealand soldiers in the First World War, Wellington; Winchester 1989: Allen & Unwin; Port Nicholson Press.

- Boyack, Nicholas / Tolerton, Jane: In the shadow of war, Auckland; New York 1990: Penguin Books.

- Crawford, John / McGibbon, Ian C. (eds.): New Zealand's Great War. New Zealand, the Allies, and the First World War, Auckland 2007: Exisle Publishing.

- Drew, H. T. B.: The war effort of New Zealand. A popular history of (a) Minor campaigns in which New Zealanders took part; (b) Services not fully dealt with in the campaign volumes; (c) The work at the bases, Auckland 1923: Whitcombe and Tombs.

- Levine, Philippa: Battle colors. Race, sex, and colonial soldiery in World War I, in: Journal of Women's History 9/4, 1998, pp. 104-130.

- Phillips, Jock / Boyack, Nicholas / Malone, E. P. (eds.): The great adventure. New Zealand soldiers describe the First World War, Wellington; Winchester 1988: Allen & Unwin; Port Nicholson Press.

- Pugsley, Christopher: The ANZAC experience. New Zealand, Australia and Empire in the First World War, Auckland 2004: Reed Pub.

- Sinclair, Keith: A destiny apart. New Zealand's search for national identity, Wellington 1986: Allen & Unwin; Port Nicholson Press.

- Tolerton, Jane: Ettie. A life of Ettie Rout, Auckland; New York 1992: Penguin.

- White, Richard: The soldier as tourist. The Australian experience of the Great War, in: War & Society 5/1, 1987, pp. 63-77, doi:10.1179/106980487790305175.

- Worthy, Scott: A debt of honour. New Zealanders' first Anzac days, in: New Zealand Journal of History 36/2, 2002, pp. 185-200.