The Czechoslovak Movement and its Territorial Aims in Hungary by the End of the War↑

The border dispute between Budapest and Prague originated from their mutual claims over the territories of present-day Slovakia. While these areas belonged to Hungary until the end of the First World War and were regarded by Budapest as a historical part of their “millenary kingdom,” the Czechs also demanded them because of their ethnic composition. They asserted that the Czechs in Austria and the Slovaks in Hungary formed a single “Czechoslovak nation”, separated during the course of history.

| Population of Slovakia | ||||||

| Total Population | Slovaks | Magyars | Germans | Rusyns | Others | |

| Hungarian census of 1910 | 2,816,912 | 57 % | 30,54 % | 6,74 % | 3,77 % | 1,73 % |

| Czechoslovak census of 1919 | 2,923,214 | 66,57 %

|

23,50 % | 4,87 % | 3,17 % | 1,89 % |

| Czechoslovak census of 1921 | 3,000,870 | 67,48 %

|

21,68 % | 4,86 % | 2,96 % | 3,01 % |

Table 1: Ethnic composition of the population of Slovakia

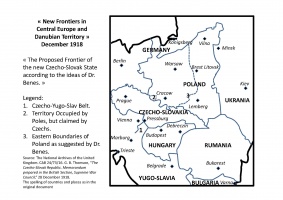

In 1914, the leading exponent of the Czechoslovakist agenda, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (1850–1937), emigrated to western Europe. With Edvard Beneš (1884–1948) and Milan Rastislav Štefánik (1880–1919), he organized the Czechoslovak resistance abroad. Masaryk wanted to include the Austrian provinces of Bohemia, Moravia and Czech Silesia, and the northern region of Hungary ("Upper lands") from Pressburg (Bratislava from 1919) to Košice, as well as a strip of borderland between Austria and Hungary in the future independent Czechoslovakia. This area would connect Czechoslovakia with Serbia through the “Slavic Corridor”. The Entente powers supported Masaryk’s group, recognizing it as the government of the future Czechoslovakia in the summer of 1918.

On 28 October 1918, Czechoslovakia’s independence was proclaimed in Prague. Two days later, the Slovak National Council adopted a declaration proclaiming the Slovak union with the Czechs. Afterwards, Masaryk was elected Czechoslovakia’s President, and Beneš became Foreign Minister. According to Beneš’s November 1918 plan, Czech troops should occupy Upper Hungary from Bratislava to Sighetu Marmației in the east. In January 1919, the Czechoslovak government suggested drawing the frontiers of Slovakia even deeper in the South – behind the Matra and the Bükke Mountains. In total, the Czechoslovak zone of interest in the Upper lands were largely extended behind the predominant Slovak regions, and targeted Ruthenian, and Magyar inhabited areas. To achieve its territorial ambitions, Prague used its control of coal supplies from Silesia to Austria and Hungary as leverage. Without foreign coal, Austria and Hungary faced the disruption of critical infrastructure and social unrest, making the Czech position very strong.

The Czechoslovak takeover of Slovakia, November 1918 – January 1919↑

By the end of October 1918, Hungary was also in revolution: the new left-wing pacifist government of Mihály Károlyi (1875–1955) proclaimed the independence of Hungary from Austria on 31 October 1918. Hoping to keep the Upper lands, Budapest engaged in simultaneous negotiations with the Entente, the Slovak National Council and Prague. On 13 November 1918, the Károlyi government and the Entente powers signed the Belgrade military convention. This armistice stipulated that Hungary's southern and southeastern corners should be occupied by the Allied armies (consisting mainly of Serbian and Romanian troops). The rest of Hungary should remain under the direct rule of Budapest. However, on 3 December 1918, the Entente notified Budapest that the Czechoslovaks must be permitted to occupy Slovakia.

On 6 December 1918, the Hungarian Defense Minister Albert Bartha (1877–1960) and the Czechoslovak representative Milan Hodža (1878–1944) agreed that the Czechoslovak army could enter the territories up until Bratislava in the South and Košice in the East. However, on 23 December 1918, the Entente issued a new Czechoslovak-Hungarian demarcation line that was more favourable to Prague. It started on the Danube River in the West, then followed the Ipoly/Ipeľ River, passing through the Rimavská Sobota to the Uzh River in the East, where it extended north until Galicia. Károlyi's government accepted this new line. Every time Budapest withdrew its troops from the Upper lands, it expected Prague to resume deliveries of Silesian coal to Hungary. By 20 January 1919, the Czechoslovak army reached the demarcation line. Despite the takeover of Slovakia by Prague, its legal status remained unclear: Prague claimed that Slovakia was an integral part of Czechoslovakia, while Budapest continued to insist that these territories de-jure belonged to Hungary. The Hungarian and Czech troops were rarely engaged in mutual hostilities. However, the weakening of state authority facilitated a significant spreading of uncontrolled uniformed violence against alleged national “enemies” – Jews, “disloyal” officials or any suspected person.

Czechoslovak-Hungarian war in April – July 1919↑

The Hungarian revolution entered a new, dramatic stage on 20 March 1919, when the Entente demanded Budapest acknowledge the extension of the Romanian occupation zone in the East. Refusing to comply, Károlyi resigned, leaving the power to the Social-Democrats, who, with the Communists, proclaimed the Hungarian Republic of Councils. The Czechoslovak authorities, fearing the spread of social disorders, introduced martial law in Slovakia. At the same time, Czechoslovakia decided to launch an operation against Hungary without the Entente's approval. Prague aimed to expand its rule behind the city of Miskolc in the South, and over the Eastern Carpathian slopes. The Czechoslovak army in Slovakia, amounting to 100,000 members, was divided into two wings. The Eastern group, led by a French military mission, occupied Subcarpathian Ruthenia, which the Hungarian army had previously evacuated, from 27–30 April 1919. Under the command of an Italian military mission, the western group entered Miskolc on 2 May, but they met the Hungarian resistance close to Salgótarján, the most important coal mining centre under the control of Budapest.

After these initial clashes, the situation on the Hungaro-Czechoslovak front stabilized for three weeks, which allowed the Red Army to grow its ranks to 110,000 soldiers. On 19 May, its northern wing launched a massive counter-offensive against the Czechoslovaks. They took back Miskolc on 20 May, Nové Zámky and Levice on 1–2 June and Košice on 6 June. Having nearly reached Poland, the Red Army separated the Eastern Czechoslovak army in Ruthenia from the retreating western group, where the Italian military command was soon replaced by the French.

On 12 June 1919 the Supreme Allied Council issued a new demarcation line between Hungary and Czechoslovakia. It largely resembled the previous line of 23 December 1918, but Ruthenia passed under Czechoslovak rule. Formally, Budapest accepted the new line, but secretly it supported the establishment of the so-called "Slovak Republic of Councils" in Eastern Slovakia on 16 June 1919. Czechoslovak-Hungarian hostilities continued until the truce of 24 June. With the complete withdrawal of the Red Army behind the new demarcation on 7 July 1919, the Slovak Republic of Councils was disbanded.

In August 1919, the Bolshevik regime in Hungary collapsed and the Romanians occupied central parts of the country, including its capital. Simultaneously, Czech troops penetrated behind the last demarcation line, occupying strategic locations like Petržalka – the southern part of the Danube near Bratislava, or Salgótarján. At the Paris Peace Conference, Beneš proposed sending Czech troops to Budapest, but this proposal was declined. In November 1919, under Entente pressure, the Romanians left Budapest, while, apart from Petržalka, the Czechoslovaks withdrew behind the June 1919 demarcation line.

The Normalisation Process between Prague and Budapest and the Trianon Peace Treaty↑

On 23 November 1919, a coalition government was formed in Budapest, which was then invited to attend the Paris Peace Conference. The new administration, dominated by right-wing politicians, restored the monarchy in Hungary under the regency of Miklós Horthy (1868–1957). While the Czechs were still reluctant to open up the coal trade between Hungary and Silesia, the Magyar counter-revolutionary authorities multiplied their efforts to return the Upper lands. Since Czechoslovakia was organized as a unitary state, Budapest hoped to gain the sympathies of the Great Powers. Therefore, while the peace terms were still discussed, it granted formal autonomy to Slovakia, and proposed holding plebiscites for self-determination within the "occupied territories". Nevertheless, the Entente decided to draw the frontiers between Hungary and Czechoslovakia upon the June 1919 delimitation line, but also decided obliging Czechoslovakia providing coal to Hungary.

Claiming that the Magyars in Czechoslovakia were oppressed by Prague, the Horthyists attempted to defend them by secretly sponsoring their political parties. Hungary, which also hosted a hundred thousand refugees from Slovakia and Ruthenia, unsuccessfully demanded their repatriation. But, Prague suspected that concerns in Budapest over the Magyar minority in Slovakia and the call for repatriation were a part of Hungarian revanchist efforts, aimed at restoring old borders.

On 4 June 1920, Hungary signed the Treaty of Trianon with the Allied and Associated Powers, including Czechoslovakia. Above all, it recognized Czechoslovak sovereignty over Slovakia and Ruthenia, but also included provisions allowing free trade, particularly in coal, between Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Poland. Hungary ratified the Trianon terms on 15 November 1920, and Czechoslovakia on 28 January 1921. Nevertheless, until the peace treaty entered into force on 26 July 1921, Budapest still considered Slovakia and Ruthenia as "Hungarian territories under foreign occupation". Czechoslovakia then opened up coal trade with Hungary. In the 1920s, both countries developed an intensive economic exchange. More importantly, the memory of the border conflict from 1918–1920 between Czechoslovakia and Hungary strongly affected their relations in the following decades. Both states feared new territorial claims, military attacks and interferences in domestic affairs from each other.

Aliaksandr Piahanau, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm

Section Editor: Robert Gerwarth

Selected Bibliography

- Hronský, Marián: The struggle for Slovakia and the Treaty of Trianon, 1918-1920, Bratislava 2001: Veda.

- Kučera, Rudolf: Exploiting victory, sinking into defeat. Uniformed violence in the creation of the new order in Czechoslovakia and Austria, 1918-1922, in: The Journal of Modern History 88/4, 2016, pp. 827-855, doi:10.1086/688969.

- Michela, Miroslav: Plans for Slovak autonomy in Hungarian policy 1918-1920, in: Historický časopis (Historical Journal) 58, 2010, pp. 53-82.

- Perman, Dagmar: The shaping of the Czechoslovak state. Diplomatic history of the boundaries of Czechoslovakia, 1914-1920, Leiden 1962: Brill.

- Piahanau, Aliaksandr: ‘Each wagon of coal should be paid for with territorial concessions.’ Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and the Coal Shortage in 1918–21, in: Diplomacy & Statecraft 34/1, 2023, pp. 86-116, doi:10.1080/09592296.2023.2188795.

- Romsics, Ignác: The dismantling of historic Hungary. The Peace Treaty of Trianon, 1920, Boulder; New York 2002: East European Monographs; Columbia University Press.