Background↑

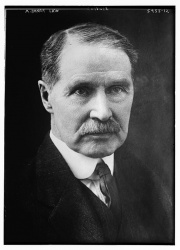

Andrew Bonar Law (1858-1923) came from an unusual background for a Conservative Party leader in this era. His father was a Presbyterian minister who had emigrated to Canada, but his mother died when he was two years old, and at the age of twelve he went to Scotland to live with his mother’s family, who were wealthy bankers in Glasgow. Bonar Law attended Glasgow High School, and at the age of sixteen took up a position in the family bank. In 1885 he became a partner in an iron merchants, and began a successful business career. In 1891 he married Annie Pitcairn Robley (1866-1909), and they had six children; it was a happy marriage, and her death in 1909 created an enduring sadness.

Pre-war political career↑

Bonar Law became a Conservative Member of Parliament in 1900. He was an effective debater through his command of facts and figures, and was a strong supporter of tariff reform. He became more prominent after the Conservative defeat in 1906, but was a surprise choice as party leader in the House of Commons in 1911. Between then and the outbreak of the war, Bonar Law led the Conservative opposition to the Liberal government’s plan to give Home Rule to Ireland, and he supported the resistance of Protestant Ulster even to the point of taking unconstitutional action. His stubborn and effective leadership of the Conservatives during this period of bitter political controversy earned him a substantial reserve of loyalty and support within the party, which was to prove invaluable during the strains of the war and immediate post-war periods.

Wartime opposition and the Asquith Coalition, 1914-1916↑

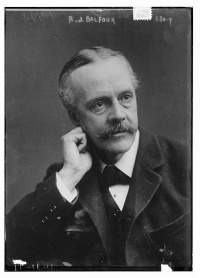

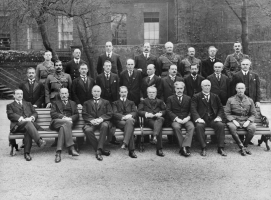

In July 1914, before the German ultimatum to Belgium, Bonar Law privately informed Herbert Henry Asquith (1852-1928), the Prime Minister, of the Conservative Party’s support for entry into the war. The next eight months were a difficult time for the Conservative Party, as they had little confidence in the Liberal government but were unable on patriotic grounds to make public criticisms. In May 1915, they entered a coalition government under Asquith, but almost all of the key offices remained in Liberal hands and Bonar Law became Colonial Secretary, a backwater position in wartime. Asquith had always had a dismissive view of Bonar Law’s abilities, and deliberately gave a more important position to his predecessor as Conservative Party leader, Arthur Balfour (1848-1930). During the next eighteen months, Bonar Law supported the introduction of conscription and gradually lost confidence in Asquith’s capacity as wartime leader. His commitment to support David Lloyd George’s (1863-1945) plan to sideline Asquith was crucial in the latter’s resignation and Lloyd George’s appointment as Prime Minister in December 1916.

The Lloyd George Coalition and afterwards, 1916-1923↑

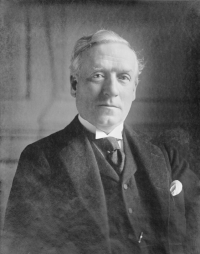

For the remainder of the war, Bonar Law worked in a close and harmonious partnership with Lloyd George. His support was the political rock upon which Lloyd George’s position depended, and one of his key roles was the management of the House of Commons. Bonar Law also held the important office of Chancellor of the Exchequer, and launched a series of successful war loans which financed a substantial part of Britain’s war expenditure. He was a member of the small War Cabinet, but did not seek to influence military strategy. At the end of the war, he supported the renewal of the coalition, and was the key figure in maintaining it until his retirement on health grounds in May 1921. After this, policy failures led to a growing revolt from below in the Conservative Party against continuing the coalition under Lloyd George at the next general election, but this feeling was dismissed by Bonar Law’s successor as leader, Austen Chamberlain (1863-1937). When the situation became critical in October 1922, concern that the Conservative Party would be fatally split prompted Bonar Law’s reluctant emergence from retirement. This was decisive in Lloyd George’s downfall. Bonar Law succeeded him as Prime Minister and won a majority in the general election of November 1922, but the terminal collapse of his health forced his resignation in May 1923. Although he did not live to see them come to fruition, his actions between 1916 and 1923 led to the recovery and consolidation of the Conservative Party’s position as the dominant political force in Britain, and to the establishment of a new two-party system in which the Labour Party displaced the Liberals as the left of centre alternative.

Stuart Ball, University of Leicester

Section Editor: Catriona Pennell

Selected Bibliography

- Adams, R. J. Q.: Bonar Law, Stanford 1999: Stanford University Press.

- Blake, Robert: The unknown prime minister. The life and times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923, London 1955: Eyre & Spottiswoode.

- Green, E. H. H.: Law, Andrew Bonar: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford 2004: Oxford University Press.

- Taylor, Andrew: Bonar Law, London 2006: Haus.