Formation in Florence and Geographical Studies↑

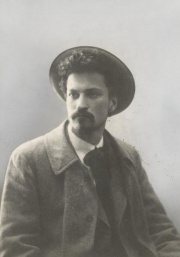

Cesare Battisti (1875-1916) was born on 4 February 1875 in Trento, the son of a merchant. He attended the local secondary school (Gymnasium), where he developed a liberal-national conscience. In 1893 he enrolled at the Florence Istituto di Studi Superiori (Higher Studies Institute). At the end of 1894 he moved to Turin, Italy; the following year he moved to Graz. During this period he became one of the leading members of the newly established Società degli studenti trentini (Society of Trentino Students), set up by Antonio Piscel (1871-1947). At this time he and Piscel were also influenced by socialist ideas. In early 1895 he started a socialist review, the first and only issue of which was confiscated by the authorities. In that same year Battisti, together with Piscel, other students, and a group of Trentino craftsmen, established the Trentino section of the Austrian Socialist Party. Battisti started working as a journalist and as a propagandist for socialist ideas, especially on topics such as expanding suffrage.

At the end of 1895 he returned to Florence to study. There he met Gaetano Salvemini (1873-1957) and Ernesta Bittanti (1871-1957), who became his fiancé and then his wife in 1899. Salvemini, Bittanti, and their cohort subscribed to an intellectual brand of socialism with romantic traits, generally characterised by theoretical links with a late form of positivism.

Battisti completed his studies in 1897 and obtained his university degree in geography. His dissertation was printed in Trento the following year. During this period he studied geographical intensively; he also founded the historical and scientific journal Tridentum (1898-1913). After moving back to Trento with Ernesta, he threw himself into the political struggle with the Socialist Party. Assisted by Piscel and Augusto Avancini (1868-1939), a member of parliament in Vienna from 1907 to 1911, Battisti became the Socialist Party’s undisputed leader.

Leader of Trentino Socialists↑

In 1900 Battisti founded the daily newspaper, Il Popolo, which was published uninterruptedly until August 1914 and was the main organ for the political struggle of the Trentino Socialists. Battisti wrote hundreds of articles for this newspaper. In local issues he focused mainly on secularizing and campaigned against clericalism in Trentino. He also fought the corrupt municipal administration and searched for a modern and rational solution to Trentino’s economic and industrial problems. At the same time, he repeatedly denounced Austrian militarism, fought to extend the right of suffrage (a common socialist goal at the time), advocated greater freedom of the press, and campaigned for the establishment of an Italian university in Trieste. The socialists shared this latter campaign with the liberals, with whom Battisti had a difficult and conflict-ridden but intense relationship.

He served as a municipal councilor (“Consigliere comunale”) in Trento (1903-1905, 1911-1914) and was elected to the Vienna parliament in 1911. In May 1914, after the electoral reform, he was elected as a representative to the Tyrolean Diet. Battisti had a reformist approach to socialism – even though he took little interest in doctrine – and put elements of resolute radicalism inspired by Giuseppe Mazzini (1805-1872) and the Italian Risorgimento into practice. Initially, his aim was for Trentino to obtain autonomy within the Austrian state, in line with the Austrian social democratic policy. Later, from 1904-1905, he became increasingly disheartened about the possibility of an Austrian federation of states; in the end, he was also disenchanted with the national policy of the Austrian Socialist Party.

The Choice for Intervention and the War↑

On 12 August 1914, soon after the war broke out, Battisti went to Italy and started an unceasing campaign for intervention against Austria through speeches, articles and publications. At this time he began to accept democratic intervention as a method for achieving his aims. This meant abandoning the socialist field (the Italian Socialist Party supported neutrality) and moving towards a cross-class position based on the condition soldiers found themselves in as a result of trench warfare. He defined this position perfectly at his last conference on the Italian Alpine troops (Gli Alpini), held in Milan on 21 April 1916. This political activity was carefully controlled by Austrian authorities, and was also regarded with concern by the Austrian socialist leader Victor Adler (1852-1918).

In 1915 he volunteered for the Italian army and was enlisted in the 5th Alpine Regiment. In the winter of 1915-1916 he collaborated with the Intelligence Office (Ufficio informazioni) of the First Army Command, whose headquarters were in Verona: here he wrote several guides of a geographical-military nature. In May 1916 he returned to fight in the mountains with the 6th Alpine Regiment as a lieutenant on the Pasubio Massif.

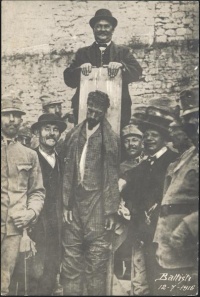

Hanging↑

On 10 July, while trying to conquer an advanced posting with his platoon, Battisti was captured on Monte Corno di Vallarsa by the Austrian army. He was executed at Trento Castle on 12 July 1916. The photographs of the hanged “martyr” caused an outcry in the media. The headquarters of the 11th Army almost immediately prohibited the circulation of these pictures, which nevertheless spread rapidly and were used by the Italian press as propaganda throughout the whole war.[1] The photographs also became the topic of a penetrating reflection in the dialogue between the Optimist and the Begrudger in Karl Kraus’ (1874-1936) play, The Last Days of Mankind (Die Letzten Tage der Menschheit), written shortly after the war.

Battisti’s legacy is rather mixed. After the Great War, he was acclaimed in Italy; his legacy was, however, also exploited by fascism. Yet he also became an inspiration for several anti-fascist groups who were part of the resistance movement, while after World War II a “normalized” version of him came to be tied to democratic ideals. Later on he became a target for a number of Italian and German minority extremist pro-Tyrolean groups.

Mirko Saltori, Museo storico del Trentino

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Translator: Claudia Marsilli

Notes

- ↑ Publishing the photograph on 23.2.1918, Benito Mussolini’s (1883-1945) newspaper Il Popolo d’Italia headlines read: “Italiani, guardate e imparate a odiare! Il martirio di Cesare Battisti fotografato dai suoi carnefici”: Italians, look and learn to hate! Cesare Battisti’s martyrdom photographed by his own executioners).

Selected Bibliography

- Biguzzi, Stefano: Cesare Battisti, Turin 2008: UTET libreria.

- Calì, Vincenzo (ed.): Addio mio caro Trentino. Cesare Battisti - Ernesta Bittanti. Carteggio, luglio 1914 - maggio 1915, Trento 1984: TEMI.

- Gatterer, Claus: Unter seinem Galgen stand Österreich. Cesare Battisti. Porträt eines 'Hochverräters', Vienna; Frankfurt a. M.; Zurich 1967: Europa Verlag.

- Leoni, Diego (ed.): Come si porta un uomo alla morte. La fotografia della cattura e dell'esecuzione di Cesare Battisti, Trento 2008: Museo storico in Trento; Provincia autonoma di Trento.

- Monteleone, Renato: Il movimento socialista nel Trentino, 1894-1914, Rome 1971: Editori riuniti.

- Monteleone, Renato (ed.) / Battisti, Cesare: Scritti politici e sociali, Florence 1966: La nuova Italia