Introduction↑

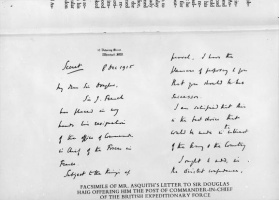

Herbert Henry Asquith (1852-1928) had been British Prime Minister for over six years at the outbreak of the First World War. He was generally regarded as a successful politician who had presided over a Liberal government that had introduced major domestic reforms in relation to old age pensions, insurance against illness and unemployment, and the power of the House of Lords. But despite initial signs of popularity, Asquith’s wartime premiership was to become associated with inefficiency, military defeat and a lack of strategic direction. Following growing criticism over insufficient production of shells for the Western Front and military setbacks at Gallipoli he formed a coalition with the Conservatives and Labour on 5 May 1915. But on 5 December 1916 he was forced to resign as Prime Minister when David Lloyd George (1863-1945), Secretary of State for War, called for a new War Committee under his chairmanship to take over the everyday running of the war.

Wartime Leader↑

On the surface Asquith’s reputation suggested that he was a natural wartime leader. In contrast to Lloyd George he had supported Britain's involvement in the Boer War and was seen as being part of the Liberal Imperialist wing of the party. He had taken a particular interest in defence matters both before and after becoming Prime Minister and had appointed himself as Secretary of State for War in April 1914.[1] His ability to keep both the United Kingdom and his party relatively united at the outbreak of war reflected a conciliatory approach that had enabled him to dominate pre-war British politics despite lacking an overall majority in the House of Commons. But Asquith’s new coalition did not reinvigorate his personal authority. Although there were some successes, notably Italy's decision to join the allies and Lloyd George’s work in wartime production at the Ministry of Munitions, his government also presided over the horrific Battle of the Somme, the Easter Rising in Ireland and political differences over the introduction of conscription. By early December 1916 he was still supported by many MPs in both the Liberal and Labour parties but with a growing alliance between Lloyd George and leading Conservatives like Andrew Bonar Law (1858-1923) and accusations of ineffectiveness exploited by the press, notably Alfred Charles William Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe’s (1865-1922) papers, his position was vulnerable. He resigned as Prime Minister and was succeeded by Lloyd George on 6 December.

Years of Opposition↑

For the remaining years of the war Asquith was Leader of the Opposition. The majority of Liberal MPs refused to support Lloyd George and the former Prime Minister appeared well placed to exploit dissatisfaction in the Allied War Council debate in November 1917 and discussion of the remit of the Supreme War Council in February 1918. But Asquith’s failure three months later to win a parliamentary vote over claims by Sir Frederick Maurice (1871-1951), Director of Military Operations, that the government had given misleading statements in relation to the conduct of the war, was to undermine his position. Apart from giving a lacklustre performance in the debate, the event also exacerbated existing tensions within the Liberal parliamentary party. Many party activists were increasingly disillusioned by Asquith’s leadership at a crucial time when Lloyd George, in alliance with the Conservatives and the press, appeared to be betraying Liberal values, and the Labour movement was in a position to exploit growing discontent.[2] In 1918 the Lloyd George coalition swept to a landslide victory with the independent Liberals losing the vast majority of their seats. Even Asquith lost his personal stronghold of East Fife, which he had represented since 1886, with the general mood of voters apparently symbolised by placards stating that "Asquith nearly lost you the War. Are you going to let him spoil the Peace?"[3]

Post-war↑

Defeat in 1918 did not mean the end of Asquith’s active involvement in British politics. In 1920 he won the Paisley by-election and returned to his former position as Leader of the Opposition. In 1923 the Liberals were reunited under his leadership and as a result of the December election, in which the party, though in third place, was able to strengthen its overall position, he held the balance of power. But Asquith’s decision in the following month to support a minority Labour administration led by James Ramsay MacDonald (1866-1937) was followed by a Conservative landslide in October 1924 and once again he lost his seat. Asquith also wrote about issues relating to the war, including in The War, its Causes and its Message (1914) and The Genesis of the War (1923). In 1925 he became Earl of Oxford and Asquith.

Garry Tregidga, University of Exeter

Section Editor: Catriona Pennell

Notes

- ↑ Quinault, Roland: Asquith, a Prime Minister at war. Issued by History Today 64/ 5, May 2014, online: http://www.historytoday.com/roland-quinault/asquith-prime-minister-war (retrieved: 30 December 2014).

- ↑ Tregidga, Garry (ed.): Killerton, Camborne and Westminster. The political correspondence of Sir Francis and Lady Acland, 1910-29, Exeter 2006, pp. 12, 89 and 121.

- ↑ Koss, Stephen: Asquith, London 1976, p. 240.

Selected Bibliography

- Brock, M. G. / Brock, Eleanor (eds.) / Asquith, Margot: Margot Asquith's Great War diary 1914-1916. The view from Downing Street, Oxford 2014: Oxford University Press

- Cassar, George H.: Asquith as war leader, London; Rio Grande, Ohio 1994: Hambledon Press.

- Jenkins, Roy Harris: Asquith, London 1964: Fontana.

- Koss, Stephen E.: Asquith, New York 1976: St. Martin's Press.

- Quinault, Roland: Asquith. A prime minister at war, in: History Today 64/5, May 2014.