Introduction↑

Field Marshal Edmund Allenby (1861-1936) was an experienced cavalry officer who held senior command positions in the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front (1914-17) before commanding the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) in its successful campaigns in Palestine from June 1917 through to the end of the First World War. From March 1919 to June 1925 he served as Special High Commissioner in Egypt, managing the British administration through a period of political unrest. Educated at Haileybury College and the Royal Military College Sandhurst, Allenby commissioned into the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons in December 1881. His early military career involved numerous African postings: he attended Staff College in 1896-97 and took part in the Second South African War, proving a tough field commander. His military career trajectory then accelerated with his promotion to major-general in 1909 and appointment as inspector-general of cavalry in 1910.

First World War: Western Front↑

Allenby went to France with the BEF in August 1914 as commander of the Cavalry Division. His handling of this over-sized four-brigade formation in the retreat from Mons was criticised, but his conduct leading the cavalry corps of two divisions in the defensive battle on the Messines-Wytschaete ridge during the First Battle of Ypres (October-November 1914) demonstrated his determination as a commander. In May 1915 he commanded the V Corps during the Second Battle of Ypres; he was then promoted to general and took charge of the Third Army in October. The static warfare of the Western Front did not allow Allenby to demonstrate any particular operational flair and he developed a reputation as a solid if unimpressive commander.

In April 1917 Allenby directed his most significant Western Front battle at Arras. The initial assault on 9 April proved a success, with a gain of nearly four miles. Within days the battle descended into a slogging match of attrition, with the commander of the BEF, Field Marshal Douglas Haig (1861-1928), increasingly interfering in the organisation of subsequent attacks. In mid-April several of the Third Army’s divisional commanders, tacitly supported by their superiors at the corps level, complained directly to Haig about Allenby’s dogged commitment to the offensive and its associated casualties. By early May Allenby accepted that continued offensives were futile and protested to Haig. The complaints of his subordinates and now his challenge to General Headquarters convinced Haig that Allenby was no longer suited to command Third Army.

First World War: Middle East↑

In the early summer of 1917 Prime Minister David Lloyd George (1863-1945) was searching for a new commander for the EEF in Palestine and chose Allenby, who saw the posting as a demotion and a punishment for his failure at Arras. Allenby inherited an army that under the command of General Archibald Murray (1860-1945) had suffered two significant defeats at Gaza in March and April. Although its logistical base and support apparatus was sound, the EEF was physically exhausted and mentally fragile. Allenby arrived on 27 June and within a week had visited the front line, listening to his subordinate commanders and their assessment of the problems they faced. A new training regime was instituted to prepare the troops for an assault on the Ottoman defensive system between Gaza and Beersheba. The command structure of the EEF was reorganised, with the former ad hoc system of command and control thrown out and a new system of three corps commands introduced: XX, XXI, and the Desert Mounted Corps (DMC) respectively under Lieutenant-Generals Philip Chetwode (1869-1950), Edward Bulfin (1862-1939), and Henry Chauvel (1865-1945). Allenby symbolically moved his headquarters forward from Cairo to Khan Yunis, close to the battlefront, and he brought in a number of experienced staff officers from the Western Front such as Louis Bols (1867-1930) as his Chief of Staff. Allenby’s reforms represented the wholesale professionalisation of the EEF. Crucially, Allenby was able to secure a significant increase in manpower and firepower, especially artillery, to support his planned offensive.

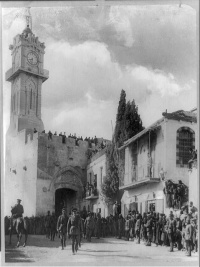

At the Third Battle of Gaza (31 October - 7 November 1917) the EEF destroyed the Ottoman defensive position in southern Palestine. The XX Corps and the DMC re-deployed inland, opposite Beersheba, and in a combined assault on 31 October seized the town; this force then turned westward and rolled up the Ottoman positions towards Gaza, forcing the Turks to retreat. Exploiting the collapse of his opponents, Allenby pursued them northwards into the Judean Hills, resulting in Jerusalem’s capture on 9 December. The entry of Allenby into the holy city was a carefully stage-managed event, filmed for the world’s cinema audiences to aid the Allied propaganda cause.

Spring 1918 witnessed a major reorganisation of the EEF, with over two-thirds of Allenby’s British infantry sent to France and Flanders; they were replaced by Indian units, many of which were newly recruited and untrained. Allenby proved adept at managing the multi-ethnic and multinational complexities of the EEF during this difficult period of reorganisation and training. His command in Palestine was not without failures, however, and two attempts to attack Amman to sever the Hejaz railway in April and May 1918 ended in defeat.

The zenith of Allenby’s tenure in command of the EEF came with the Battle of Megiddo, launched on 19 September 1918. Following a hurricane bombardment, British and Indian infantry punched a hole through the Ottoman positions on the coastal plain north of Jaffa. Advancing rapidly in their wake was the DMC, which harried the Ottoman retreat across northern Palestine and on to Damascus, captured on 1 October. By the end of the month the EEF had effectively pushed Ottoman forces out of the Levant. These operations were conducted alongside Hashemite Arab forces, advised by Colonel T. E. Lawrence (1888-1935), who fought on the right flank of the EEF advance. Their impact on the military outcome of the campaign in the Levant was minimal, but Allenby was aware that the Arab Revolt had considerable political value and that it would be better to have local auxiliaries fighting alongside the EEF than against it. Allenby’s success was one of a series of defeats that contributed to the Ottoman decision to sue for peace in October 1918. The British military historian Basil Liddell Hart (1895-1970) declared that Megiddo was among "the most completely decisive battles in all history."[1] The Ottoman army was, however, acutely short of resources and manpower in 1918, which helps explain how a battlefield defeat was turned into a rout.

Post-War↑

Allenby’s career after 1918 was in many ways as challenging as the campaigns of the war. His military success was rewarded with promotion to field marshal and his raising to the peerage as first Viscount Allenby of Megiddo and Felixstowe. In March 1919 he was appointed Special High Commissioner to Egypt and tasked with restoring order following the 1919 Egyptian Revolution. Alongside Bulfin, he coordinated a repressive security campaign which, by the end of May, left over 750 Egyptians dead and another 1,000 wounded. Nonetheless, Allenby combined repression with political concessions to the Egyptian nationalists, which some members of the British administration and commercial community saw as weakness. Over the next three years Allenby tried to steer a difficult course between maintaining security and managing the complex politics of Egypt. Demobilisation problems in the EEF in May 1919, which came close to mutiny among the men in the Suez Canal base area, only highlighted to Allenby that maintaining a large garrison and using force to keep Egypt quiescent was not a viable long-term solution. In early 1922 Allenby, exasperated at the dilatory approach of the Lloyd George government, forced London’s hand to end the British protectorate over Egypt. Political unrest would, however, last into the mid-1930s and beyond. All the same, as Allenby’s most significant biographer Archibald Wavell (1883-1950), phrased it, this period witnessed "Allenby’s principal contribution to political history."[2]

In June 1925 Allenby retired, spending his later years as president of the National Cadet Force. He also began to adopt a much more internationalist stance which at times bordered on pacifism, becoming a vice-president of the League of Nations Union in 1931. In part, this stance was a product of the death of his only child, Horace Michael Hynman Allenby (1898-1917), on the Western Front in July 1917, which many of his fellow senior officers noted had a significant effect upon him. Allenby’s personal life revolved around his marriage to Adelaide Mabel Chapman (1869-1942) in 1896, with whom he shared a deep love of nature and travel. He died on 14 May 1936 and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

A number of his fellow officers noted Allenby’s irascible character, which became worse once he assumed higher ranks and responsibilities in the run up to the Great War. To some of his subordinates he was known as "The Bull" and was feared for his temper, although by the time he commanded the EEF he had moderated his approach. His military successes in Palestine were eulogised by interwar military theorists, most notably Liddell Hart and the future World War II general Archibald Wavell, the suggestion being that they pointed in the direction of a more mobile form of warfare different from that of the Western Front. Allenby’s military career was a mixed one and like many commanders he stumbled at moments as he tried to adjust to the challenges of the Great War. In Palestine he was freer to operate independently and to take his time preparing set-piece battles and well-resourced pursuit operations. His real skill, however, was as a commander in the age of imperial war and crisis, proving adept at leading an army drawn from across the British Empire and at managing Egypt through its early steps towards independence from British rule.

James E. Kitchen, Royal Military Academy Sandhurst

Section Editor: Pınar Üre

Notes

Selected Bibliography

- Allenby, Edmund / Hughes, Matthew (ed.): Allenby in Palestine. The Middle East correspondence of Field Marshal Viscount Allenby, June 1917-October 1919, Stroud 2004: Sutton

- Fantauzzo, Justin: Dead Sea fruit. Edmund Allenby, the First World War and the politics of personal loss, in: First World War Studies 7/3, 2016, pp. 287-302.

- Hughes, Matthew: Allenby and British strategy in the Middle East, 1917-1919, London 1999: Frank Cass.

- James, Lawrence: Imperial warrior. The life and times of Field-Marshal Viscount Allenby, 1861-1936, London 1993: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Wavell, Archibald Percival: Allenby. A study in greatness, 2 volumes, New York 1940-1943: Oxford University Press