Origins↑

The Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) was created in March 1916 out of the remnants of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (MEF), which had been evacuated from Gallipoli, and the Force in Egypt, which was tasked with the protection of the frontiers and the Suez Canal. General Archibald Murray (1860-1945), then commander of the MEF, succeeded to the command of this new combined formation, which soon saw ten of its fourteen infantry divisions dispatched to other theatres – predominantly the Western Front – and thus acted as an imperial strategic reserve. The EEF was from its inception the archetypal multi-ethnic and multinational British imperial formation, comprising of troops drawn from across the British Isles (predominantly Territorial Force soldiers), India, Australia, New Zealand, and the West Indies.

1916 Operations in Sinai↑

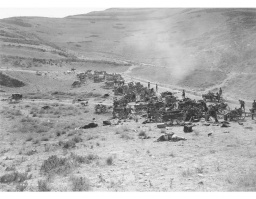

The principal task of the EEF in spring 1916 was the defence of the Suez Canal, the key communications link of the British Empire. To this end, large parts of the EEF were engaged in building and occupying a series of interlocking defensive posts to the east of the Canal. From taking over the EEF Murray had been keen to push the defensive line out into Sinai, gradually advancing it towards the Egypt-Palestine border, allowing him to defend Egypt with fewer troops, freeing up manpower to be used on other fronts. As the EEF advanced along the northern edge of Sinai it pushed out a railway, wire netting road and water pipeline behind it to ensure its logistical support. At Romani on 4 August 1916, the EEF conducted a successful defensive battle that was followed by a faltering pursuit of the Ottomans across northern Sinai in the second half of 1916. This culminated with the destruction of the El Arish garrison at the battle of Magdhaba on 23 December and then the capture of the border post defences at Rafah on 9 January 1917.

1917 Operations in Southern Palestine↑

To ensure the destruction of Ottoman forces in southern Palestine before they had a chance to withdraw, Murray attempted a coup de main against the garrison in Gaza. A confused battle ensued on 26 March 1917 in which the EEF’s mounted arm attempted to envelop the town from the north and east while its infantry attacked from the south. Early morning sea fog, muddled command and control arrangements, inadequate reconnaissance, and poor infantry-artillery cooperation resulted in failure. First Gaza cost the EEF 3,967 casualties compared to losses of only 1,372 for the Ottomans. Murray’s report to the War Office, however, presented the action as an attritional victory for the EEF, estimating Ottoman losses at over 8,000. The War Office, eager to capitalise on success in Mesopotamia and influenced by Murray’s appreciation, ordered the EEF to renew its advance and to try to reach Jerusalem. This resulted in the disastrous second battle of Gaza on 19 April, which saw the EEF fail to take any of the Turkish defensive positions and suffer 6,444 casualties.

Two defeats at Gaza ended Murray’s command of the EEF and he was replaced in June by General Edmund Allenby (1861-1936), formerly commander of the British Expeditionary Force's (BEF) Third Army. Allenby instituted a major reorganisation of the EEF’s formations, dispensing with the ad hoc command and control arrangements used during 1916 and early 1917, and creating three corps: XX and XXI Infantry Corps (commanded respectively by Lieutenant-Generals Philip Chetwode (1869-1950) and Edward Bulfin (1862-1939)), and the Desert Mounted Corps (commanded by Lieutenant-General Harry Chauvel (1865-1945)). Combined with an increase in troops numbers – the EEF now possessed seven infantry divisions and three mounted divisions – and its artillery resources, Allenby was able to use the EEF to smash through the Ottoman Gaza-Beersheba line defences during the third battle of Gaza (31 October – 7 November 1917). Over the course of the next month the EEF pursued the Ottoman army northwards, reaching a line just north of Jaffa before re-orienting its operations eastwards to advance on Jerusalem, occupied on 9 December. The difficult engagements at Third Gaza and in the Judean Hills meant this triumph came at the cost of 21,559 casualties by the end of 1917.

1918 Operations in Palestine and Syria↑

Spring 1918 saw the EEF expand its operations eastwards into the Jordan Valley, followed by two abortive attempts to reach Amman and cut the railway line south to the Hejaz in order to aid the Arab Revolt. More importantly, the opening months of 1918 saw the EEF fundamentally transformed as all but one of its infantry divisions had three-quarters of their British soldiers replaced by Indian sepoys. The Indianisation of the EEF was the product of long-term manpower problems in the British Army as a result of the costly battles of 1916-17; this process was, however, accelerated after the shock of the 1918 German March offensive. The summer of 1918 was spent training the newly arrived sepoys, many of whom had no combat experience, and integrating them into the EEF’s existing formations.

The Indianised EEF launched a major offensive against the Ottoman army in Palestine – by then a severely depleted force due to disease, manpower shortages, and materiel problems – on 19 September 1918, with Allenby using his infantry to drive open a gap along the coastal plane north of Jaffa through which he then unleashed his mounted troops. Within days the EEF’s cavalry had encircled the bulk of the Ottoman army in northern Palestine, capturing over 75,000 Ottoman soldiers, and by 1 October its Australian Light Horsemen had entered Damascus. By the Ottoman armistice on 31 October the EEF’s most advanced mounted units had reached positions a few miles north of Aleppo, over 300 miles from their start line; the battle of Megiddo was the war’s most successful large-scale use of cavalry on the battlefield. Although the EEF’s campaign had not been the principal factor driving the Ottoman regime to end their war effort – the collapse of Bulgaria and the severing of the link to Germany was key – it contributed to the destruction of the Ottoman Empire’s hold on its Levant territories. Megiddo and the pursuit northwards came at a relatively light cost to the EEF of only 5,666 casualties.

After the War↑

In March-April 1919, a large bulk of the EEF was committed to the suppression of the Egyptian Revolution, restoring control through the liberal use of force. The shift from wartime operations to post-war imperial policing proved unpopular with the EEF’s rank and file as it delayed their demobilisation, leading to large-scale unrest in many units in May 1919. Following the rapid demobilisation of most of its British and Anzac units the remnants of the EEF, by then largely an Indian army formation, acted as an army of occupation in the former Ottoman Levant until mid-1921, being replaced by the new civil authorities of the Syrian and Palestinian mandates.

James E. Kitchen, Royal Military Academy Sandhurst

Section Editors: Alexandre Toumarkine; Erol Ülker

Selected Bibliography

- Falls, Cyril: Military operations. Egypt and Palestine, volume 2, London 1930: His Majesty's Stationary Office.

- Hughes, Matthew: Allenby and British strategy in the Middle East, 1917-1919, London 1999: Frank Cass.

- Kitchen, James E.: The British Imperial Army in the Middle East. Morale and military identity in the Sinai and Palestine campaigns, 1916-18, London 2014: Bloomsbury.

- MacMunn, George / Falls, Cyril: Military operations. Egypt and Palestine, volume 1, London 1928: His Majesty's Stationery Office.

- Woodward, David R.: Forgotten soldiers of the First World War. Lost voices from the Middle Eastern front, Stroud 2006: Tempus.