Introduction↑

The region around the Western Front during the Great War was almost certainly the most diverse, multicultural place in the world at the time. Troops came from around the globe to fight, but the front and areas behind it were teeming not only with soldiers but also with laborers. Modern industrial war required large numbers of workers to keep soldiers in the field and civilians behind the front supplied with necessities. With so many European men in uniform, the nations at war turned to other sources of labor. Women entered the industrial workforce in larger numbers than before, and some armies relied on prisoners of war and occupied civilian populations (especially in Belgium) to provide labor.[1] In addition, large numbers of Europeans migrated to France to take jobs, especially from Spain, Greece, Italy, and Portugal.[2] But greater cultural and even racial diversity also shaped the world of work and war, as men came from beyond Europe to toil for the belligerent powers. Africans formed an important part of this group.

Africans found themselves laboring in Europe during the war because the major belligerents possessed significant colonial possessions in Africa. To be sure, non-European or “colonial” workers came from other parts of the globe as well. Some 50,000 men from French Indochina contributed to the French war effort, as well as 37,000 Chinese workers.[3] Great Britain brought another 100,000 Chinese workers to the Western Front, who worked in the same conditions as other imperial subjects even though China was not formally a colony.[4] The Western Front was not the only place where men from outside of Europe labored. Great Britain deployed many Indian workers in East Africa and the Middle East, and some 100,000 Egyptians served in these theaters as well.[5] Africans worked in support of the war effort in Africa itself, as well, including at least one million porters who carried supplies in East Africa.[6] For the European theater, it is also important to remember that many of the 500,000 men France brought from its colonies to serve as soldiers (450,000 of them from Africa) often performed war-related labor in addition to or instead of combat.[7]

Yet this article will concern itself primarily with Africans explicitly recruited and deployed as workers. Most of these men, at least 130,000 of them, came from France’s North African possessions: Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco. Approximately 5,000 laborers came from Madagascar, though many of the 45,000 soldiers from the island served as military laborers, not as combat infantry. The Union of South Africa, a British dominion, deployed more than 20,000 black South Africans in France as part of the South African Native Labour Contingent, while the British army also deployed 10,000-15,000 Egyptians, primarily in French port cities. Although relatively small in number in the context of a war that involved many millions of people around the world, the labor carried out by these men had a significant impact not only on their lives and those of their families, but also on European social and political life and colonial politics during and after the war. Above all, the labor of Africans in Europe during the war focused a glaring light on questions of race and the hierarchies of colonial rule, and on the roles these would play over the rest of the history of the 20th century.

Race, Labor, and War in France, 1914-1918↑

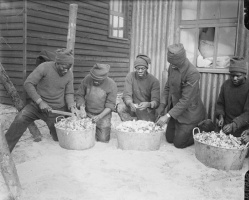

France, the site of most of the war’s most decisive battles on the Western Front, hosted the largest number of workers from Africa, outside of Africa itself. Some of these men worked in ports loading and unloading ships, but most worked in manufacturing munitions and agriculture. The latter involved physically demanding manual labor such as planting crops, tending fields and livestock, and bringing in the harvest, tasks that would have been familiar to the majority of these men recruited from rural areas in the colonies. Jobs in munitions production covered a range of activities, from working with dangerous chemicals and explosives, to operating metal presses that produced artillery shells, digging in quarries, and transporting raw materials and finished products. Men worked in factories, mines, ports, trucks, depots, and construction sites (some of these last near the front, where workers helped build and maintain the thousands of miles of trenches and associated barracks, emplacements, roads, and more). African laborers lived in barracks, often under strict military discipline even if they were not formally enlisted as soldiers. These living quarters were often improvised, substandard, and unhygienic, though authorities worked throughout the war to improve these conditions.

A far more consistent living condition throughout the war was segregation, as French and especially British and South African authorities strove to separate colonial subjects from European soldiers and civilians. Prevailing racist ideas held that European women had to be protected from the uncontrolled sexuality of “black” and “brown” men, and from diseases thought to be endemic to colonial subjects. Equally threatening were left-wing political ideas and militant labor activism that could be carried back to the colonies in the minds of these men, as well as relatively egalitarian treatment by Europeans – particularly those who seemed willing to cross or ignore the color line when it came to love and sex. This all set threatening precedents for a colonial order that relied upon strict racial hierarchies. Yet friendly treatment was certainly not all these workers encountered, and as more came to France as the war continued, incidents of discrimination and even violence increased. Resentment at perceived undercutting of wages or filling positions at the expense of domestic laborers, and above all anger at the way imported labor allowed more French men to be sent to the front, added to simple racism and fear to create combustible social tensions in many French cities and towns.

Before turning to the main sources of African workers in France during the war – North Africa, Madagascar, and South Africa – it is worth noting the somewhat anomalous experience of the few West Africans who performed primarily as laborers for at least part of the war. France recruited men from its vast federation of territories in West Africa, l’Afrique Occidentale Française, or the AOF, exclusively as soldiers, since martial race theories held these men in high esteem as combatants, while at the same time doubting their qualities as disciplined and skilled workers. In short, the stereotyped assessments of the tirailleurs sénégalais by French officials as primitive, simple, and loyal led them to believe they were useful on the battlefield, but not in the factory. Yet, in 1916, the French army designated thirteen battalions of tirailleurs (some 12,000 men) as “staging troops,” that is, soldiers in uniform tasked more or less exclusively as laborers to directly support army operations. This direct support extended to working on railroad maintenance and in munitions factories far from the front. The number of these units progressively diminished over the course of the next year, as military, political, and colonial officials all agreed that the best use of West Africans was as combat soldiers and that their time working in factories in particular was a distraction from proper military training and corrosive of morale, discipline, and hygiene.[8] These soldiers were paid at the same rates as other laborers, including native French workers, in addition to their army salaries.[9]

In many respects, West Africans’ experiences were not analogous to those of other Africans working in France during the war, since West Africans remained strictly within the military hierarchy and virtually all of them returned to regular soldiering at the front. But European notions of race determined all Africans’ experiences in myriad ways. One general worried, for example, that the relatively high rates of pay the men enjoyed would spoil them: “With their childish mentality, the Senegalese would not be slow to consider [a pay raise] as a right and the desired result (increased productivity) would be at risk of not being attained.”[10] In the end, racial stereotypes about the particular aptitude of “savage” West Africans for combat and the inaptitude of other “races” for war, such as Indochinese and Madagascans, meant that men from the latter regions progressively replaced even the small number of West Africans tasked with labor rather than fighting.[11]

North African Labor↑

Of the 140,000-195,000 North Africans who served as laborers in France during the war, about two-thirds came from Algeria, almost one-third perhaps equally divided between Moroccans and Tunisians, along with some 10,000-15,000 Egyptians.[12] The experience of Egyptian laborers in France is less well researched, but they worked as stevedores in the French ports of Marseilles, Calais, Boulogne, as well as Taranto in Italy.[13] Most French colonial subjects were recruited “administratively,” that is, signed to official contracts by the government, though many also traveled to France as so-called “free” workers who migrated and found work on their own initiative. In addition, officials acknowledged that an unknown, but probably substantial number of men crossed the Mediterranean and worked clandestinely.

The French state and employers turned to North Africans most readily and recruited them in the largest numbers among the various regions that made up the empire because of proximity to the metropole and the front, and because of prewar experiences exploiting labor in Algeria in particular. Several thousand Algerians from the mountainous Kabylia region were in fact already working in France before the war began. But racial stereotypes played a role as well. As a Ministry of War report framed it in 1916, North Africa was the best place to recruit workers “capable of hard and difficult work.” But this came at a price. If the Moroccan worker was “robust, sober, hard-working, thrifty,” he also “takes to every vice of his environment, and is easily led astray.” This meant that Moroccans, like other North Africans, were subject to “constant surveillance,” and authorities even argued that they should be forced to save part of their salary, rather than being left free to spend it on vice.[14] The experiences of Moroccans and other colonial workers during the war make it clear that some were able to evade the strict surveillance of the French state. Yet this very surveillance and the effort required to evade it might have led workers to the clandestine pleasures of the underworld of cities like Marseille. However, it is also probable that their behavior was no different from any group of young men living and working abroad. What French authorities feared above all was the supposed dangerous aspect of their racial “otherness”.

The overall view of North Africans was that they were marked by greed. This had its uses, according to the official view: the promise of money was effective in recruiting them. But racial stereotypes transformed this into critiques, for instance, of Tunisians who had to be watched attentively lest they take the least opportunity to commit theft. For them, and all North Africans, “moral supervision” was a critical ingredient of French policy.[15] This imperative, and protecting the French civilian population from various forms of racial contamination, lay behind strict regimentation of colonial workers, including their confinement to segregated barracks, often far from the city centers. It is true that many North African workers were, strictly speaking, civilians, but contravention of the military discipline they were often subject to could result in military courts martial and other militarized punishments.[16]

Long-standing French prejudices with regard to Algerians, which marked France’s 130-year history in the North African country, divided the population into two groups, Arabs and Kabyles.[17] According to this perspective, Arabs were insubordinate and poor workers, and were eventually put under military discipline, even though they were recruited as civilians. Kabyles were supposedly much better, largely because they were, according to the dominant, official logic, less Islamicized, lived in a temperate climate, and in general seemed racially “more white” and thus culturally closer to native French. Reputed to be hard workers, thrifty, ambitious, energetic, and sober, they were useful in all kinds of work: agriculture and viticulture, mines, factories, construction, and more. Officials sometimes accused them indulging in vice, to be sure, but they seemed less in need of surveillance as well. Their “taste for travel, inherent in the race” also meant that they transplanted well into metropolitan France.[18]

Race and racism played a role in the daily life of North African workers in France, not only shaping European attitudes toward colonial workers, but also provoking violence. The relatively large number of colonial workers from this region made them a frequent target of malice. This was driven by resentment on the part of the French that the presence of colonial workers freed up more native French men for frontline military service, allegedly drove down wages, reduced the leverage of organized labor, and provided opportunities to mix with French women, who also made up an increased proportion of the wartime labor force. Violent incidents increased as a result of the nationwide “crisis of morale” in 1917-1918. The racial “otherness” of North African men made them prominent targets for native, and nativist, antipathy and aggression.[19] Women laborers on strike in Paris accosted a North African employed as gardener, hitting him in the face and calling him a “dirty Sidi coming to France to eat the bread of French workers.” Though he escaped further violence by defending himself with a water hose and help from the police, others were not always so lucky. An attack on North African workers in Brest escalated into a riot that left five workers dead and thirty-two wounded, while violence against Moroccans in Le Havre resulted in a melee that killed some fifteen people and wounded many more.[20] These and many other incidents were the direct result of an explosive mix of racial animus and wartime conditions.

Despite the frequency and importance of this sort of violence, for many North Africans the most salient aspect of their experience laboring in France had to do with the work itself. This was often difficult and exhausting. An official report in 1917 described North Africans in Lyon working ten-hour days, alternating between day and night shifts, loading large artillery shells:

Some workers wrote letters describing what it felt like to work under such conditions. One Tunisian wrote to his parents,

And it was not just the work that caused suffering. Another Tunisian complained, “I’m employed by a crook who scarcely lets me sleep… I swear to God that our food is served in utensils fit only for dogs,” while another wrote,

It is clear from workers’ correspondence that not all of them suffered such indignities, and many found greater work opportunities than they could find at home in North Africa, but the pains of work, exile, racial discrimination, and culture clash figured prominently in their wartime experiences.

Madagascan Labor↑

Colonial subjects came to France from Madagascar in far lower numbers than from North Africa, both as workers and soldiers. And in fact, though some 50,000 Madagascans were recruited for wartime service, 90 percent of them served as soldiers, not laborers. Yet the story of Madagascan workers during the war is not reducible to the experiences of the roughly 5,000 men who were contracted to work as civilians in war industries. Very few Madagascan soldiers served in combat, owing to French military prejudices that considered them racially unsuited to warfare. This meant that the vast majority of so-called tirailleurs malgaches worked as staging troops, performing labor in direct support of military operations. Also, given the existence of relatively well-educated elements among the population on the island, comparatively more Madagascans served in roles such as nursing or clerical and administrative staff than in other units made up of colonial subjects. So, in the end, the wartime experience of most Madagascans was of work, not fighting.[24] For instance, twenty-five of the twenty-six battalions of tirailleurs malgaches in the army at the end of 1917 were serving as staging troops, including three working in factories and other work sites far from the front.[25]

Race and racism ordered the lives of Madagascan workers in France, just as it did other workers from the colonies. First of all, stereotypes characterizing these men as effeminate and unfit for war were so strong that even the successful record of the lone Madagascan combat infantry battalion, plus the successful deployment of thousands of Madagascan support troops in the heavy artillery, were not enough to change official views during and after the war. As with Indochinese workers and soldiers, the most common adjective used to describe Madagascans was “doux”: “gentle” or “soft.” A doctoral thesis completed in 1919, claiming to analyze the “lessons of the war” on the subject of foreign labor, ranked Madagascans and Martinicans last among various categories of workers, describing them as “docile and weak.”[26] Still, during the war the military and government were happy to make use of Madagascan labor behind the front and in factories. The flip side of negative stereotypes were comparatively positive ones, though still racialist. A 1916 Ministry of War report declared that Madagascans were “more intelligent on average than the negroes of [continental] Africa” and could be used even as skilled laborers, as the example of using some of them as shoemakers in military workshops had shown. They were “doux,” and worked enthusiastically, though their output was only around 60 percent that of native French workers.[27] Even when assigned to combat units in the heavy artillery, Madagascans served most often as support troops, performing labor, because of what one general deemed their low intelligence.[28]

Workers and soldiers from Madagascar were not immune from the violence that racism and resentment provoked toward foreign workers during the war. In Toulouse in January 1918, what amounted to a pitched battle broke out between French and Madagascan workers. One Madagascan worker connected this violence with sexual jealousy on the part of French men, some of whom called him and his friends “dirty niggers” and resented “the favors [French] women show the Malagasy.”[29] Postal censorship records make clear that colonial workers from all areas of the French empire engaged in relationships with French women, from visiting prostitutes to marrying and having children, and everything in between. This showed that not everyone in France was interested in policing the color line with violence or afraid to cross it, and was a radical departure from the norm colonial subjects had grown accustomed to back home in the colonies. As one Madagascan noted of the dramatic difference between the attitudes of white women in France and in the colony: “What to tell you of white women? Down there, we fear them. Here they come to us and solicit us by the attraction of their charm.”[30] The novelty of this situation made a profound impression on these young men, and constitutes one of the most important aspects of their experience laboring in France, often to the consternation of postal censors, military and political officials, and French men in general.[31]

The South African Native Labour Contingent↑

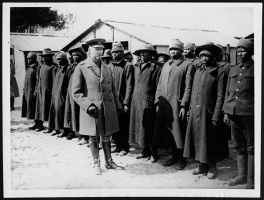

When, in the second half of 1916, British forces faced a serious labor shortage on the Western Front, in part because of the huge effort and losses of the Somme Offensive that summer, imperial officials appealed to the Union of South Africa to make a greater direct contribution to the war effort in Europe. The Union government acquiesced to the request for black African workers from South Africa with grave misgivings. From the beginning, officials referred to the effort as an “experiment,” and made clear that they would control the conditions of service of these men carefully, so as to avoid conveying to black Africans any sense of their worth and necessity to the war effort – and most of all their equality with whites. At a minimum, segregation and strict supervision and control by white South African officers would reign in France, a regime that officials baldly called “Martial Law.” Nonetheless, white South Africans vociferously expressed anxieties about the effects of service in France on black South Africans, whose changed attitudes upon return home might “destroy white hierarchy” and lead to demands for voting and other political rights.[32]

Despite these anxieties, the government announced the formation of the South African Native Labour Contingent (SANLC) in September. Recruitment focused primarily on the Transvaal and the Cape Colony, with smaller numbers of men enlisting from the Natal, the Orange Free State, Bechuanaland, Basutoland, and Swaziland. Enlistments developed slowly, since many black Africans did not see why they should sail so far away to fight in a war that did not seem to concern them. By January 1918, some 25,000 men had enlisted in the SANLC, well short of the original goal of 40,000. Still, just over 20,000 of these men traveled to Europe, where they supported the war effort by working as stevedores in ports and performing other heavy labor on railways and roads, and in quarries and forests. These men impressed military officials with prodigious feats of labor – one unit loaded a train with 14 tons of ammunition per man in seven hours.[33] Such efforts may seem all the more remarkable in light of the living conditions the men of the SANLC endured. They suffered from the cold, damp weather of northeastern France and from often poor sanitary conditions in camps, as did many soldiers and workers on the Western Front. But black South Africans suffered greater segregation and policing than their counterparts among French colonial workers. One white officer in the SANLC candidly described the camps his men lived in as “identical” to those housing enemy prisoners of war, though even the latter often offered inmates better conditions.[34] Contravention of the rules and the discipline of white officers could result in harsh punishment, even tragedy. When an officer imprisoned a worker for disobeying an order to do his washing inside rather than outside the camp, the friends of the accused demanded an explanation. The officer refused, and so the men tried to free their compatriot by force. The resulting fracas left thirteen black Africans dead at the hands of their white officers.[35]

The South African authorities kept this tragedy quiet, but another, greater disaster befell hundreds of members of the SANLC before they even reached Europe. On 21 February 1917, the SS Mendi was sailing in dense fog near the Isle of Wight off the coast of Great Britain, carrying a battalion of the SANLC, when it collided with another ship. The accident killed over 600 black Africans, and highlighted the perils of service for all Africans in the Great War, whether serving as laborers or soldiers.[36] White South Africans recognized the shipwreck as a tragedy, but it was clear that many regarded the effects of war service on black African consciousness as an equal or greater disaster. Some of the worst fears of those who argued against recruiting native labor for the SANLC seemed to be borne out. Draconian security and tight military discipline did not prevent all African laborers from having experiences that shined an unflattering light on the racial regime of South Africa, and pointed to possibilities for a less racist and discriminatory society. Africans reported occasionally working alongside white men in conditions of equality, sometimes even making friends with white English or Frenchmen. Some workers had opportunities, usually very limited, to interact with white women, a true nightmare for the officers. And one worker reported the astonishing effect of a visit to his camp of a group of French political officials. Included among them was a black African who had won election to the French parliament and now held an important position in the government. One black South African wondered to his colleagues, “Would such a thing ever happen in our country?” Some suggested, “It might…”[37]

This conjured white South Africans’ greatest fear: black Africans demanding racial and political equality and ending the racist social order in the Union. Segregation and control had not worked perfectly in France, and though critics exaggerated Africans’ mixing with French civilians and women, that any of this had occurred was an intolerable affront to “the racial and political status quo.”[38] The dangerous experiment had failed, the government halted recruitment for the SANLC in December 1917, and repatriation of the units in France began. These men had played an important role in the war – making up 20-25 percent of the total British labor force on the Western Front in 1917 – but they were all home before the Armistice of November 1918.[39]

Conclusion: Race, Labor, and Empire after 1918↑

The South African government was not alone in wanting to expedite the departure of African laborers from Europe. The French government also obviously regarded the use of “exotic” labor from places such as Africa as an experiment, and wound the experiment down with what one historian has called “breathtaking rapidity.” Scarcely six months after the armistice, fewer than 30,000 colonial workers (including Chinese and Indochinese) remained in France. North Africans, who had had begun to develop very small communities of migrant workers in France even before the war, were a particular target of police raids seeking those who overstayed their welcome.[40] The massive importation of colonial labor during the war did not set a precedent, then, for a multicultural French working class, but it did constitute a turning point of sorts. The expulsion of Africans and Asians in 1919 contributed to the “racialization” of the French working class and cultural construction of France as a “white” nation.[41]

Repatriation sent African workers back home, no doubt to the satisfaction of many of them. If they no longer benefited from the opportunities afforded by an industrial economy on a war footing, they also escaped the harsh regimentation of their lives in and out of work in France. To be sure, they probably also missed the glimpses of a more racially egalitarian society that they could catch when they escaped official control, an important element of which were opportunities for friendship, love, and sex. While black South Africans returned to the iron rule of a settler colony on the way to both nationhood under white rule and apartheid, even French colonial subjects came back home to a regime increasingly turning to exploitative economic policies, including forced labor, in order to show that colonialism “paid.”[42] As one historian has put it, in light of this perhaps it is more accurate to regard the events of 1919 as a mere “reassignment of colonial labor.”[43]

The question of labor would remain important in Africa after the First World War ended in 1918. Returning soldiers proved difficult to contain within the traditional and colonial political and social orders, to be sure.[44] But workers had also seen new places, had new experiences, and witnessed new possibilities. The connections between wartime work experiences and increased labor militancy in the colonies, perhaps influenced by exposure to French organized labor and socialism and communism while in Europe, are not always straightforward or clear. But officials were on their guard for this possibility, and certainly strike action in the postwar period in Guinea included former Great War soldiers as leading actors, in any case.[45] And in Algeria, there were signs that increased labor militancy did derive from contacts with the French metropolitan proletariat during the war.[46] If it is important not to exaggerate the influence of organized labor and left-wing ideology among Africans who worked in Europe during the war, intensified European efforts to exploit African labor, and to justify it ideologically, were certainly critical in shaping life in the colonies during the interwar period and through the period of decolonization.[47] A good example of this is the way resentment over the often brutal and unscrupulous recruitment of the Egyptian Labor Corps by the British and their indigenous agents inflamed Egypt’s rural peasants and helped shape their attitudes and actions during the revolutionary turmoil there in 1919.[48]

A final consequence of Africans working in Europe during the war was the establishment of a tradition of migration northward in search of economic opportunity. For even though European officials expelled Africans from European soil as quickly as possible in 1918-1919, the memories of higher wages and social opportunities remained and inspired migration in subsequent decades.[49] As one Algerian worker wrote home from France in 1917, “France is the country of work and money.” But as a compatriot observed, this could come at a price, since some French people were good and treated Algerians well, while others were bad and mistreated and cheated colonial workers.[50] And certainly the experience of racism and discrimination against African migrants, if not universal, was and is at least in part a continuing legacy of the First World War. As an Algerian migrant noted of his arrival in Marseille in 1926, “On disembarkation, the humiliations began: the ‘superior’ race got off first; as for us, the ‘inferior’ race, we were kept back until the customs officers and police had searched us in a revolting manner.”[51] How many African migrants today, arriving in Europe in search of work and opportunity, could tell similar stories?

Richard Fogarty, University at Albany, SUNY

Section Editor: Melvin Page

Notes

- ↑ On women, see Downs, Laura Lee: War Work, in: Winter, Jay, (ed.): The Cambridge History of the First World War. Civil Society, volume 3, Cambridge 2014 and Grayzel, Susan R.: Women and the First World War, New York 2013. See Jones, Heather: Violence Against Prisoners of War in the First World War. Britain, France, and Germany, 1914-1920, Cambridge 2011.

- ↑ See Horne, John: Immigrant Workers in France during World War I, in: French Historical Studies 14/1 (1985), pp. 57-88, and Cross, Gary: Immigrant Workers in Industrial France, Philadelphia 1983.

- ↑ Le Van Ho, Mireille: Des vietnamiens dans la Grande Guerre, Paris 2014; Ma, Li (ed.): Les Travailleurs chinois dans la Première Guerre mondiale, Paris 2012.

- ↑ Xu, Guoqi: Strangers on the Western Front. Chinese Workers in the Great War, Cambridge, M. A. 2011.

- ↑ Anderson, Kyle J.: The Egyptian Labor Corps. Workers, Peasants, and the State in World War I, in: International Journal of Middle East Studies 49/1 (2017), pp. 5-24.

- ↑ Hodges, Geoffrey: Kariakor. The Carrier Corps. The Story of the Military Labour Forces in the Conquest of German East Africa, 1914-1918, Nairobi 1997; Killingray, David: Beasts of Burden. British West African Carriers in the First World War, in: Canadian Journal of African Studies 12 (1979), pp. 5-23 and Killingray, David: Labour Exploitation for Military Campaigns in British Colonial Africa, 1807-1945, in: Journal of Contemporary History 24 (1989), pp. 483-501.

- ↑ See Fogarty, Richard S.: Race and War in France. Colonial Subjects in the French Army, 1914-1918, Baltimore 2008.

- ↑ See, for example, the complaints of General Simonin, Inspecteur des Contingents Indigènes, to the Ministry of War, Rapport, 1 novembre 1916, in: Sevice Historique de la Défense (SHD) 7N1990. See also Michel, Marc: L’Appel à l’Afrique. Contributions et réactions à l’effort de guerre in AOF (1914-1919), Paris 1982, pp. 365-366.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 374.

- ↑ SHD 7N1990: Rapport du Général Simonin, Inspecteur des Contingnets Indigènes to the Ministry of War, 23 novembre 1916.

- ↑ See the voluminous correspondence on the subject of West African soldiers as workers in SHD 7N440: Dossier des pièces relatives à l’effectation des tirailleurs sénégalais aux Usines du Minstère de l’Armament, 1916.

- ↑ The sources give various and often conflicting figures – for instance, some indicate that roughly twice as many Moroccan workers migrated to France as Tunisians, but other sources indicate a rough equivalence. The sources are not clear, either, about whether 10,000 or 15,000 Egyptians labored in France. The existence of clandestine workers, not officially recorded, and of double and even triple counting of men who made several trips on short-term contracts further problematizes the statistics. See Meynier, Gilbert: L’Algérie révélée. La guerre de 1914-1918 et le premier quart du XXe siècle, Geneva 1981, pp. 405-412; Horne, Immigrant Workers 1985; Nogaro, Bertrand / Weil, Lucien: La Main-d'Oeuvre Étrangère & Coloniale pendant la guerre, Paris 1926; Bernard, Augustin: L’Afrique du Nord pendant la guerre, Paris 1926; and Anderson, Egyptian Labor Corps 2017.

- ↑ Ibid.; Ruiz, Mario: Photography and the Egyptian Labor Corps in Wartime Palestine, 1917-1918, in: Jerusalem Quarterly 56-57 (2014), pp. 52-66, and Ruiz, Mario: The Egyptian Labor Corps, issued by World War I in the Middle East and North Africa, online: https://blogs.commons.georgetown.edu/world-war-i-in-the-middle-east/seminar-participants/web-projects/mario-ruiz-the-egyptian-labor-corps/ (retrieved: 28 October 2019).

- ↑ Archives Nationales de France (AN) 94AP135: “Note relative au recrutement de la main-d’oeuvre coloniale Nord-Africaine et Chinois,” 16 avril 1916.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Horne, Immigrant Workers 1985, pp. 75-76.

- ↑ See Lorcin, Patricia: Imperial Identities. Stereotyping, Prejudice and Race in Colonial Algeria, London 1995.

- ↑ AN 94AP135: “Note relative au recrutement de la main-d’oeuvre coloniale Nord-Africaine et Chinois,” 16 avril 1916.

- ↑ Stovall, Tyler: The Color Line behind the Lines. Racial Violence in France during the Great War, in: American Historical Review 103/3 (1998), pp. 737-769.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 754-756, 764.

- ↑ Stovall, Tyler: Colour-Blind France? Colonial Workers during the First World War, in: Race and Class 35/2 (1993), p. 44.

- ↑ Horne, Immigrant Workers 1985, p. 77.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 78-79.

- ↑ See Fogarty, Race and War in France 2008.

- ↑ Razafindranaly, Jacques: Les soldats de la Grande île. D'une guerre à l'autre, 1895-1918, Paris 2000, pp. 302-303.

- ↑ Lugand, Joseph: L’immigration des ouvriers étrangers et les enseignements de la guerre, Paris 1919, p. 39.

- ↑ AN 94AP135: “Note relative au recrutement de la main-d’oeuvre coloniale Nord-Africaine et Chinois,” 16 avril 1916.

- ↑ SHD 16N588: “Rapport du général Paloque, sur la valeur des contingents malgaches, versés dans les batteries lourdes,” 26 juillet 1918.

- ↑ Stovall, The Color Line behind the Lines 1998, pp. 754, 761.

- ↑ SHD 7N997: Contrôle Postal Malgache, Rapport du mois de Septembre 1917.

- ↑ See Fogarty, Race and War in France 2008; Fogarty, Richard S.: Gender and Race, in: Grayzel, Susan R. / Proctor, Tammy M. (eds.): Gender and the Great War, New York 2017, pp. 67-90; and Stovall, Tyler: Love, Labor, and Race. Colonial Men and White Women in France during the Great War, in: Stovall, Tyler / Van den Abeele, Georges (eds.): French Civilization and Its Discontents. Nationalism, Colonialism, Race, Lanham, Maryland 2003, pp. 297-321.

- ↑ Winegard, Timothy: Indigenous Peoples of the British Dominions and the First World War, Cambridge 2012, p. 138.

- ↑ Willan, B. P.: The South African Native Labour Contingent, 1916-1918, in: Journal of African History 19/1 (1978), pp. 61-62.

- ↑ Grundlingh, Albert: Fighting Their Own War. South African Blacks and the First World War, Johannesburg 1987, p. 106.

- ↑ Willan, South African Native Labour 1978, p. 79.

- ↑ Grundlingh, Albert: Mutating Memories and the Making of a Myth. Remembering the SS Mendi Disaster, 1917-2007, in: South African Historical Journal 63/1 (2011), pp. 20-37.

- ↑ Willan, South African Native Labour 1978, p. 79. The black French politician is not named, but Willan is assuredly correct in surmising that it had to have been Blaise Diagne, deputy from Senegal and eventual Commissioner General of Colonial Troops.

- ↑ Winegard, Indigneous Peoples 2012, p. 183.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 182.

- ↑ Stovall, Tyler: Paris and the Spirit of 1919. Consumer Struggles, Transnationalism, and Revolution, Cambridge 2012, pp. 127-128.

- ↑ Dornel, Laurent: L’appel à la main d’oeuvre étrangère et coloniale pendant la Grande Guerre. Un tournant dans l’histoire de l’immigration?, in: Migrations Société 6/156 (2014), pp. 51-68. See also Stovall, Paris and the Spirit of 1919 2012, and Stovall, The Color Line Behind the Lines 1998.

- ↑ Sarraut, Albert: La mise en valeur des colonies françaises. Paris 1923, p. 51. Sarraut argued that the colonial contribution to victory in the Great War had shown that French colonialism “paid,” and pointed the way to even greater dividends after the war. For how this translated into policies on forced labor in French West Africa, see Conklin, Alice L.: A Mission to Civilize. France and West Africa, 1895-1930, Stanford 1997.

- ↑ Stovall, Paris and the Spirit of 1919 2012, p. 139.

- ↑ Lunn, Joe: Memoirs of the Maelstrom. A Senegalese Oral History of the First World War, Portsmouth 1999; Summers, Anne / Johnson, R. W.: World War I Conscription and Social Change in Guinea, in: Journal of African History 19/1 (1978), pp. 25-38.

- ↑ Summers / Johnson, World War I Conscription 1978, pp. 29-31.

- ↑ Meynier, L’Algérie révélée 1981, pp. 690-709.

- ↑ Cooper, Frederick: Decolonization and African Society. The Labor Question in French and British Africa, Cambridge 1996.

- ↑ Anderson, Egyptian Labor Corps 2017, pp. 19-20.

- ↑ MacMaster, Neil: Colonial Migrants and Racism. Algerians in France, 1900-62, London 1997, p. 65.

- ↑ Meynier, L’Algérie révélée 1981, p. 473-474.

- ↑ MacMaster, Colonial Migrants and Racism 1997, p. 74.

Selected Bibliography

- Bernard, Augustin: L'Afrique du Nord pendant la guerre, Paris; New Haven 1926: Les Presses Universitaires de France; Yale University Press.

- Gontard, Maurice: Madagascar pendant la première guerre mondiale, Tananarive 1969: Éditions universitaires.

- Grundlingh, Albert M.: Mutating memories and the making of a myth. Remembering the SS Mendi disaster, 1917-2007, in: South African Historical Journal 63/1, 2011, pp. 20-37.

- Grundlingh, Albert M.: Fighting their own war. South African Blacks and the First World War, Johannesburg 1987: Ravan Press.

- Horne, John: Immigrant workers in France during World War I, in: French Historical Studies 14/1, 1985, pp. 57-88, doi:10.2307/286414.

- MacMaster, Neil: Colonial migrants and racism. Algerians in France, 1900-62, New York 1997: St. Martin's Press.

- Meynier, Gilbert: L'Algérie révélée. La guerre de 1914-1918 et le premier quart du XXe siècle, Geneva 1981: Droz.

- Nogaro, Bertrand / Wiel, Lucien: La main-d'œuvre étrangère & coloniale pendant la guerre, Paris; New Haven 1926: Les Presses universitaires de France; Yale University Press.

- Razafindranaly, Jacques: Les soldats de la Grande île. D'une guerre à l'autre, 1895-1918, Paris 2000: L'Harmattan.

- Stovall, Tyler: The color line behind the lines. Racial violence in France during the Great War, in: The American Historical Review 103/2, 1998, pp. 737-769.

- Stovall, Tyler: Colour-blind France? Colonial workers during the First World War, in: Race & Class 35/2, 1993, pp. 33-55.

- Stovall, Tyler Edward: Love, labor, and race. Colonial men and white women in France during the Great War, in: Stovall, Tyler Edward / Van den Abbeele, Georges (eds.): French civilization and its discontents. Nationalism, colonialism, race, Lanham 2003: Lexington Books, pp. 297-321.

- Summers, Anne; Johnson, R. W.: World War I. Conscription and social change in Guinea, in: The Journal of African History 19/1, 1978, pp. 25-38.

- Willan, Brian P.: The South African Native Labour Contingent, 1916-1918, in: The Journal of African History 19/1, 1978, pp. 61-86.

- Winegard, Timothy C.: Indigenous peoples of the British dominions and the First World War, New York 2011: Cambridge University Press.