Youth and Education↑

Victor Emmanuel (1869-1947) was the only child of Umberto I, King of Italy (1844-1900). On 29 July 1900, at age thirty, Victor Emmanuel ascended the throne following his father’s assassination. His early years showed evidence that, by the standards of the Savoy monarchy, he was a man committed to constitutional government.

Victor Emmanuel played an important role in military affairs and foreign politics. He supported Giovanni Giolitti’s (1842-1928) campaign in Libya in 1911 and, despite reassuring Berlin and Vienna of Rome’s commitment to their Triple Alliance, he promoted a gradual reconciliation with the powers of the Triple Entente. The Italian monarch had a personal antipathy for Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941); he did not trust the Austrians either, feeling treated more like a client than an ally.

From Neutrality to War↑

At the outbreak of the First World War, Victor Emmanuel supported the decision of Italian Prime Minister Antonio Salandra (1853-1931) to remain neutral on the grounds that the defensive nature of the Triple Alliance did not give rise to a casus foederis. During the months that followed, both the Entente and the Central Powers courted Italy. Victor Emmanuel officially supported a cautious policy that would avoid rushing Italy into war for which it was not prepared. But in private conversations, he was more explicit about his ideas:

After the Battle of the Marne had frustrated German hopes for a quick and decisive victory, the Italian military establishment, including Chief of Naval Staff Paolo Thaon di Revel (1857-1948) and Colonel Francesco Avogadro (1857-1920), the king’s military adjutant, became convinced that in the long run the Entente’s resources – in particular those of Britain – would prevail. Victor Emmanuel therefore favoured the secret talks that led to the Treaty of London, which proclaimed Italy’s entrance into the fray on the side of the Entente at the end of May 1915 in exchange for territorial gains in the “unredeemed lands” and Dalmatia. The treaty was signed on 26 April 1915; Salandra presented the parliament with the fait accompli the following week. Most politicians opposed the war, however, and the lack of an interventionist majority in parliament forced Salandra to resign on 13 May 1915. Victor Emmanuel rejected Salandra’s resignation and made it clear to Giolitti, the leader of the neutralists, that he felt personally committed to the London pact. The Salandra government was reshuffled. The king confirmed Sidney Sonnino (1847-1922), an Entente supporter, as foreign minister and approved the replacement of Giulio Rubini (1844-1917), the minister of finance, and Domenico Grandi (1849-1937), the minister of war, with Paolo Carcano (1843-1918) and Vittorio Zupelli (1859-1945), respectively. Rubini and Grandi had opposed the rearmament of the Italian army for financial reasons. By supporting their removal the king played an important part in pressuring the parliament to approve the Treaty of London. War on Austria-Hungary was finally declared on 23 May 1915.

World War I↑

At the outbreak of hostilities, the king was constantly close to the frontline. He established his headquarters at Villa Linussa (later renamed Villa Italia) in Torreano di Martignacco, near Udine, where the Italian army’s Comando Supremo was located. Every morning, he left for the front with a small escort of aides and visited both the trenches and the villages behind the front, demonstrating considerable courage in the face of enemy gunfire. He often visited the Comando Supremo as well, giving his advice to the Italian generals that he chanced to meet, but without overstepping the authority of Chief of Staff Luigi Cadorna (1850-1928).

After Salandra’s fall, following the Austrian offensive in the Trentino (15 May-27 June 1916) Victor Emmanuel dealt with the political crisis with calm and determination. He appointed Paolo Boselli (1838-1932), aged seventy-eight, as the new prime minister, despite the disapproval of many who called for a more energetic figure. The king believed that an old patriot and experienced politician like Boselli was the right man to rally the Italian ruling class. Boselli formed a larger government along the lines of the French Union Sacrée, which included some transformist socialists.

The king’s role became even more important after the defeat at Caporetto (24 October-12 November 1917). With the enemy on Italian soil, the Boselli government collapsed. The king called Vittorio Emanuele Orlando (1860-1952) to form a new cabinet. Orlando, who had been Boselli’s interior minister and a fervent interventionist, maintained control over the Interior Ministry as well as the premiership.

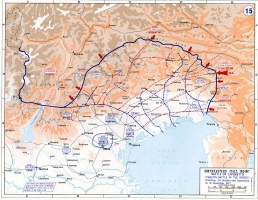

Orlando and Victor Emmanuel met with the British and French prime ministers, David Lloyd George (1863-1945) and Paul Painlevé (1863-1933), at Rapallo and Peschiera (5 and 8 November 1917) to discuss the military emergency in Italy. Among the many decisions that were taken, including the replacement of Cadorna with Armando Diaz (1861-1928) as the new Italian chief of staff, was the establishment of the new frontline along the Piave River. The British and the French believed that the Mincio would be easier to defend, but Victor Emanuel supported Diaz’s decision to stand firm on the Piave in order to prevent the fall of Venice.

Italian historiography has emphasised the king’s role at Peschiera, stressing that Victor Emmanuel’s calm impressed the British prime minister and reassured the Allies about Italy’s determination to fight to the end. When victory came in November 1918, Victor Emmanuel III was saluted by Diaz as the Duce Supremo who had led the nation through three years of grave sacrifices and had managed to fulfil his ancestors’ mission: completing the unification of Italy.

Aftermath↑

The First World War strengthened the Savoy’s prestige but economic decline and a chronic political crisis favoured the rise of paramilitary formations that threatened the liberal institutions. The threat of a social revolution in the wake of the events that occurred in Russia in 1917 caused major concern in Rome.

Italian public opinion was further irritated by the disappointing outcome of the Versailles Peace Treaty. The myth of the “mutilated victory” quickly spread across Italy. Victor Emmanuel III looked favourably to Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) as the man who could guarantee stabilisation and restore order. On 30 October 1922 Mussolini was appointed prime minister.

Stefano Marcuzzi, University of Oxford

Section Editor: Marco Mondini

Notes

- ↑ Martini, Ferdinando: Diario. 1914-1918, edited by G. De Rosa, Milan 1966, p. 401 (2 May 1915).

Selected Bibliography

- Azzoni Avogadro, Francesco: L'amico del Re. Il diario di guerra inedito dell'aiutante di campo di Vittorio Emanuele III, Udine 2009: Gaspari editore.

- Bertoldi, Silvio: Vittorio Emanuele III. Un re tra le due guerre e il fascismo, Turin 2002: UTET libreria.

- Martini, Ferdinando, Rosa, Gabriele de (ed.): Diario, 1914-1918, Milan 1966: Mondadori.

- Solaro del Borgo, Vittorio: Giornate di guerra del re soldato, Milan 1931: Mondadori.

- Ungari, Andrea: La scelta di un re, in: Ungari, Andrea / Orsina, Giovanni (eds.): L'Italia neutrale 1914-1915, Rome 2016: Rodrigo editore, pp. 79-100.