Reasons and Preparations↑

The Italo-Turkish War (1911-1912) was fought over Ottoman Libya, populated by 1.5 to 2.5 million (mostly Arab and Berber Muslims) living in coastal cities (including some 1,000 Italian citizens) and those living mainly as tribesmen in the hinterland. The Ottoman military there numbered about 5,000 infantrymen and 350 cavalry.

The war broke out because Italy claimed that, as the heir of the Roman Empire, she was entitled to rule over former Roman territories. Since Libya was the sole Mediterranean region not claimed by another European power, it was the only territory Italy could dominate. Viewing it as her "Fourth Shore", Italy expected to solve her high unemployment and emigration issues by settling poor Italians there. Initially Italy tried to achieve this through peaceful penetration, but facing Ottoman restrictions, she claimed that her citizens were discriminated and that she had to gain control over Libya by force. In preparation for this, Italy concluded agreements with European powers allowing her a free hand in Libya. The timing of the war was set by Italian fears that international developments would prevent the realization of this aim.

An Italian ultimatum reached the Ottoman government on 28 September 1911, to be accepted within twenty-four hours. It stated Italy's decision to expand her authority over Libya, otherwise she threatened to use force. The Ottomans responded on 29 September trying to negotiate, which was unacceptable to the Italians, who declared war later that day.

The War↑

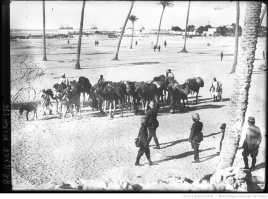

A naval blockade was set by Italy to prevent Ottoman reinforcements from reaching Libya. Italy presumed that the occupation would be easy, believing that the indigenous population hated the Ottomans and would welcome the Italians. The occupying force (numbering some 44,500 troops) reached the Libyan coast on 1 October 1911.

Italy called on the Ottomans in Tripoli to surrender on 2 October 1911 and bombarded Tripoli the following day. Since the Italian naval guns were of a longer range than the Ottoman ground guns, the city defenses were destroyed. The Ottoman military command, realizing that the balance of power was against them, decided to retreat, and launch the resistance from the hinterland. Consequently, when on 4 October 1911 the Italians landed in Tripoli, they faced no resistance. The occupation of additional coastal cities followed, but stopped there, and despite her meager territorial control, Italy declared her sovereignty over Libya on 5 November 1911: it was regarded as a return to, not an annexation of, lost homeland territories.

The resistance benefitted from imperial and local sources. Although the Ottoman government opposed sending reinforcements to Libya due to pressing needs elsewhere, and despite the Italian naval blockade, several dozen Ottoman volunteers, equipment and funding reached Libya through Egypt, Tunisia and small hidden harbors, assisted by local Arab Muslim tribesmen and border patrol agents who supported the Libyan resistance. Prominent among the volunteers were Ismail Enver Pasha (1881–1922), the Minister of War during World War I, and Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881-1938), the founder of modern Turkey. The majority of the resistance was composed of 40,000 to 50,000 indigenous Libyans, some of whom had short military training and were aware of modern military tactics, but most of whom were accustomed only to guerrilla warfare in small tribal units led by their chiefs. The Ottomans became the top commanders building the resistance, training it, and planning operations carried out by companies populated on a tribal basis and commanded by professional officers and local chiefs.

On 23 and 26 October 1911, in the outskirts of Tripoli, the resistance attacked Italian troops killing several hundred. The attackers were repelled and Italy severely punished the indigenous population, killing over 4,000. This ended the illusion many Italians held regarding the attitude of the population towards them and the impression held by many Italians that occupying Libya would be easy; this also strengthened the resoluteness of the resistance to continue fighting.

The resistance prevented an Italian advance but was unable to ward off the Italians. On the other hand, the tribesmen were not accustomed to a lengthy static war, only to guerrilla warfare, and felt that they had agricultural tasks to perform. The Ottomans, too, felt that they could be of better use elsewhere, especially as violent opposition grew in the Balkans. Thus, over time, some volunteers left Libya and local fighters returned home. The Italians were frustrated that the occupation entered into a standstill, making it expensive and requiring a force reaching 100,000. Still, the situation in Libya did not change despite Italian military superiority, including the first use of the air force in combat for reconnaissance and bombardment, the first tactical use of armored cars, and the use of modern machine guns and wireless telegraphy. Both sides realized the need to find other ways to end the war.

The Ottoman government was aware of the difficulties in overcoming the occupation. But since Libya was the last Ottoman stronghold in Africa, and in view of the emerging Arab nationalism, they felt they could not relinquish Muslim Libya to a little regarded Christian nation who held only a small part of the region. Consequently, steadfast official statements against any surrender in Libya notwithstanding, the Ottoman government realized it had to reach an agreement with Italy, while keeping some authority over Libya.

Italy was ready to discuss terms with the Ottomans in order to end the war, but refused to lose Libya. Consequently, while talks went on in Europe, Italy decided to pressure the Ottomans by spreading the war and bombarding Ottoman targets, culminating with the occupation of Rhodes and the Dodecanese in May 1912.

Termination and Results↑

The outbreak of the First Balkan War (8 October 1912) forced both parties to reach a diplomatic solution with the Peace Treaty of Ouchy (18 October 1912). It was interpreted differently by both sides, and Italy postponed parts of its implementation. The treaty entitled the Ottoman Empire to grant autonomy to the Libyan population under the Ottoman sultan in his role as the Caliph, and to appoint two Ottoman officials, but Italy accepted only the representative of the Sultan and not the religious appointee. Most of the Ottoman military left Libya, but since some remained, Italy refused to vacate the Dodecanese and Rhodes and return them to the Ottomans.

Until World War I broke out, Italy managed to occupy western Libya, but had difficulties in the east due to a strong local force headed by the Sanusi sufi order. These gains were lost once the war broke out: Italy focused on the European front, and the Ottomans renewed their involvement in Libya with German support, in cooperation with local forces. Only by the early 1930s did Italy conclude her occupation of Libya, which lasted for another decade. Considered weak as a result of the Italo-Turkish War, internal conflicts grew in the Ottoman Empire over national and ethnic divisions, with continuing internal fervor in the Balkans, being one of the causes for World War I.

Rachel Simon, Princeton University

Section Editor: Alexandre Toumarkine

Selected Bibliography

- Childs, Timothy Winston: Italo-Turkish diplomacy and the war over Libya, 1911-1912, Leiden; New York 1990: E. J. Brill.

- Simon, Rachel: Libya between Ottomanism and nationalism. The Ottoman involvement in Libya during the war with Italy (1911-1919), Berlin 1987: K. Schwarz.

- Ungari, Andrea / Micheletta, Luca (eds.): The Libyan War 1911-1912, Newcastle upon Tyne 2013: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Vandervort, Bruce: To the fourth shore. Italy's war for Libya, 1911-1912, Rome 2012: Stato Maggiore dell'esercito, Ufficio storico.