Introduction: Heading into a "Defensive War"↑

One of the most significant – yet least discussed – characteristics of the First World War is that it was basically a conflict among millions of uniformed civilians. For the first time European nations made use of conscript armies, which had taken shape everywhere (with the exception of Britain) in the 1870s. These armies comprised young men from all social classes – workers, peasants, young men of the bourgeoisie and aristocracy – who were all, in principle, obliged to perform military service but had only served in the active army for a short time during their training, between two to five years.

With such armies, states could no longer conduct wars in the traditional sense, "as a continuation of politics by other means." Moreover, rulers knew long before 1914 that a "great war" could in the future only be carried out in the name of "national defense." In the years before the war, when imperialist tensions involved the constant threat of war (the Moroccan crises of 1905 and 1911, the Bosnian annexation crisis of 1908), European Socialists in the Second International had announced that they might respond to an “imperialist war” with a general strike or "revolution." The danger of collective revolutionary action in the event of war was in fact admittedly low, largely because the German Social Democrats and their leader August Bebel (1840-1913) opposed such action. The reason was that the great majority of German Social Democrats, like the French Socialists, distinguished between offensive and defensive wars. Should the fatherland be threatened, they wanted to be ready to take up arms.[1] Still, there seemed to be a great danger that the Socialist masses in both countries would take to the streets to protest against an "imperialist war" if one appeared imminent.

Therefore, during the July Crisis of 1914, rulers placed great store in demonstrating that their nations were on the defensive. The German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg (1856-1921) was determined to "portray Russia as the aggressor" (Fritz Fischer), because he knew that the Social Democrats could only be dissuaded from anti-war protests if – as Bebel had repeatedly asserted – it was a question of confronting the "blood tsar."[2] On 27 July 1914, in the midst of the July crisis, Kurt Riezler (1882-1955), the confidant of the chancellor, wrote in his diary:

Shortly thereafter, Riezler observed in his diary:

During the July crisis the French government also put a priority on doing everything to demonstrate the country’s defensive posture to the Socialist and bourgeois left, who together had held a clear majority in parliament since May 1914 and were anything but supporters of the Franco-Russian alliance. René Viviani (1863-1925), the left-Republican head of the government, consequently ordered – to the dismay of the Chief of the General Staff, Joseph Joffre (1852-1931) – that French troops remain a (purely symbolic) ten kilometers behind the border during mobilization. After the German declaration of war on 3 August 1914, President Raymond Poincaré (1860-1934) noted with relief in his diary:

For reasons that inhered in its military system, Germany was unable to wait. The German deployment plan – the so-called "Schlieffen Plan" of 1906, which had been devised and adopted without consultation with the responsible civilian leadership – called for an immediate offensive against France at the start of the war. Only then, Alfred von Schlieffen (1833-1913) believed, would it be possible to defeat France within four weeks, then turn all the country’s forces against Russia, a power whose mobilization the German general regarded as a cumbersome process that would take at least three weeks to complete.[6]

Germany, August 1914: Necessity Knows no Law↑

Germany thus attacked on 3 August 1914, advancing through neutral Belgium in violation of international law. However, as Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg declared in the Reichstag on 4 August:

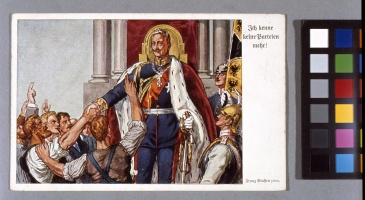

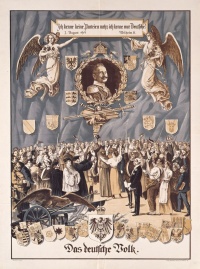

During his speech from the throne at the opening of the Reichstag, Wilhelm II, the German Emperor (1859-1941), repeated what he had already proclaimed to the crowd a day earlier from the balcony of the Royal Palace in Berlin: "I no longer know any party; I know only Germans." The Reichstag responded to this proclamation with an “tumultuous bravo,” which only intensified when the emperor added “off the cuff”:

And that is what happened. However, the Socialist "comrades" were not present for this scene. As was the custom, they had not been invited to the Emperor’s speech, which took place not in the Reichstag itself but in the "White Hall" of the Royal Palace. They would probably not have gone in any case.

In the Reichstag that afternoon, after a speech by Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg, the extraordinary credits demanded by the government to finance the war were unanimously approved "without further debate." Even the extreme left of the Social Democratic Reichstag delegation - Karl Liebknecht (1871-1919), Georg Ledebour (1850-1947), Hugo Haase (1863-1919) - was persuaded to accept the war credits, although these had been highly controversial in both the party and parliamentary delegation in the preceding days.[9] Still, the party discipline’s confirmed that, at this moment, no one was prepared or emotionally able to resist the spell of the "Burgfrieden"![10]

In this session of Reichstag, the theme of subsequent political discourse was already fully developed. "Against a world of enemies," Germany’s situation that was so threatening that the "scrap of paper" (“Fetzen Papier”)[11] - the guarantee of Belgian neutrality that Prussia had cosigned in 1839 – could play no role. The theme, which Wilhelm II announced in many variations during his appearances, was that Germany was in a defensive war. This assertion culminated in the famous words he uttered on 6 August:

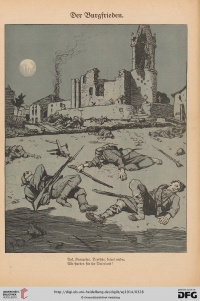

The term "Burgfrieden," which spontaneously came into use in August 1914 (it is not known who first used it), describes a domestic ceasefire which the inhabitants of a besieged medieval fortress were obliged to observe. This truce prohibited quarreling or conflict within the fortress walls, which served as the community’s defense. As the "Lexikon des Mittelalters" laconically explains: "A fortification had military value only if its garrison lived together peacefully."[13] In fact, the Germans in 1914 had no doubt that the fatherland had been attacked and that the country thus found itself in a legitimate defensive posture. The medieval “Burgfrieden” seemed therefore to describe the new situation precisely. Contemporaries characterized this national unity, which was as spontaneous as it was unforeseen, as a miracle. Thereafter, this “August Experience” (Augusterlebnis) lived on in collective memory as the promise of a better but irretrievably lost world. The Nazi regime subsequently tried to satisfy this longing with the vision of a national community, the “Volksgemeinschaft”.[14]

France, August 1914: Consolidation against Aggression↑

If unity in Germany was perceived a kind of miracle, simultaneous developments in France were even more miraculous.[15] The conviction that France had become the victim of aggression by Germany, its “hereditary enemy,” created unity in France which persisted, despite a number of challenges, throughout the war. This fact is not surprising, though, given that the Germans had in fact carried the war into France and occupied ten departments. The astonishing consensus about a purely defensive war also reflected the fact that, during the last two years before the war, the discussion of armaments in France had rested on the premise that Germany was planning an attack on France. Across party divisions, unanimity reigned that France needed to do everything possible to strengthen its defenses. Intense debate focused only on the “how” of providing the best defense against a German attack.[16] Even the Socialists, who, under the leadership of Jean Jaurès (1859-1914), vehemently objected to the specific project of the government and the bourgeois and conservative parties, stressed their readiness to ensure national defense in the event of German aggression. In keeping with the principles of the Second International, they had vowed with all their power, if necessary with a "revolutionary general strike," to oppose war - but only an "imperialist war." As a consequence, the discussion of armaments centered on the threat that an aggressive Germany posed to France. Thus the events of 1914 seemed merely to confirm a long-held conviction.

Even as the July Crisis worsened, calls came in France finally to put aside domestic political squabbles in view of the imminent threat of war from Germany. On 29 July, the left-leaning "La Lanterne" demanded an "armistice" among the parties.[17] On 2 August, the French Council of Ministers decided to forgo the planned arrest of the leaders of revolutionary syndicalism and other left-wing radicals. As was publicly known, their names had been placed on a list called "Carnet B." This decision, which represented a gesture of national solidarity in the face of the aggressor, was also immediately made known to the public.[18]

Under these circumstances, the funeral of Jean Jaurès on 3 August, who had been murdered on the evening of 31 July by a nationalist fanatic, itself became a demonstration of the new national unity. Here the leader of the revolutionary Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT), Léon Jouhaux (1879-1954), delievered a speech that sent a strong signal to all potential critics of the war on the left:

With this spontaneous outburst, Jouhaux redirected the longstanding struggle of the revolutionary syndicalists against militarism and war without seeming to abandon his principles altogether. No longer were the French government and the "ruling class" the syndicalists’ primary target; the German enemy was. After the war, Jouhaux was widely criticized for this about-face, but he vehemently defended himself, arguing that in the panic of the war’s outbreak he would have been massacred by his own comrades had he acted otherwise.[20]

Another critical signal of national unity lay in the fact that not only all the ministers, but also the leaders of the parliamentary and extra-parliamentary right attended the funeral of Jean Jaurès. Even those who had just a few days earlier been mortal enemies of Jaurès were present, like Maurice Barrès (1862-1923), the bard of French nationalism.

Less well known than the integration of the left in the Union sacrée was the discontinuation of official harassment of "congrégations" – the various Catholic religious orders that had been viewed with extreme suspicion after the separation of church and state in 1905. This was a sensational departure from established left-Republican practices in response to the national emergency.[21]

To this day, President Raymond Poincaré’s message to the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate on 4 August epitomizes the Union sacrée, the sacred unity of all Frenchmen in defense of the fatherland:[22]

The position articulated in this quote is easy to comprehend. It rested on the belief, which was anchored in the French public, that German aggression alone had caused the war. “Sacred union”? At the time no one was offended that the president of an emphatically secular republic should use such metaphors. Given the incontrovertible fact that the advancing German armies had already drawn close to France, the sacred union was neither questioned nor contested.

"Sacred Enthusiasm"↑

During the critical days of mobilization at the war’s outset, outbreaks of collective "enthusiasm" over the war took place in both countries, albeit more intensely in Germany. In the German historiography of the First World War, this phenomenon is known as the “Spirit of 1914” or the “Augusterlebnis”. Everywhere, soldiers were sent off with flowers, and railroad cars displayed brash slogans from the War of 1870 like "A Berlin!" (in French) or "Off to Paris, the tip of my sword is itching”. The view long prevailed in the scholarly literature that the “Spirit of 1914” reflected belligerence and nationalistic arrogance in Germany.[24] However, since the 1990s and the beginning of more intensive research into the cultural history of the Great War, another view has become dominant. These outbursts of collective hysteria were particularly indigenous to large cities, where mobilized soldiers gathered en masse, waiting to be dispatched to the front. Enthusiasm was a phenomenon of the city streets. It was not shared in small towns and rural areas, which made up the largest part of the country in both France and in Germany.[25] Here, anxiety and concern prevailed over practical questions - like who, if the young men were off at war, would bring in the harvest that was now ready.

Ernst Jünger (1895-1998) aptly described the mood of rural Germany at the moment the mobilization order was announced:

To assess the "Spirit of 1914" properly, it is important to understand what Jünger described as "deep and mighty enthusiasm." Again and again, reference was made to a "sacred" enthusiasm, to "soaring hearts" (Hoch die Herzen). In his chronicle of these events, which he published in 1914, Ignaz Jastrow (1856-1937), an economist and professor at the Commercial University (Handelshochschule) in Berlin, also tried to specify what had happened:

Likewise, Arnold Tänzer (1871-1937), one of many Jewish volunteers in 1914, wrote in his memoirs:

The same perception of war predominated among France’s largely rural population. The shock over German mobilization did not suddenly surge into a belief that French retaliation and the reconquest of Alsace-Lorraine were close at hand. In fact, these possibilities were hardly discussed. Instead, the French self-image as collective victim of profoundly unjustified German aggression became manifest. This fact alone explains the determination with which mobilized soldiers moved out. For them, it was simply a matter of defending the imperiled fatherland.[29]

The Union sacrée represented anything but total French unity. It was pragmatic in nature – a consensus about the need to take a defensive stand, but involved no expectation of definitively overcoming the deep divisions between left and right or between the clerical establishment and its opponents. On 26 August, the largely Radical government of René Viviani was reshuffled. In this way, the government was to work more efficiently and correspond better to the Union sacrée. Including Socialist ministers in the government presented no difficulties. Given the circumstances, the Parti socialiste (Section française de l’Internationale Ouvrière, or SFIO) had no qualms about abandoning the International’s prohibition against participating in a "bourgeois" government. Jules Guesde (1845-1922), who was once again the leader of the party after the death of Jean Jaurès, was appointed minister without portfolio. Another leading socialist, Marcel Sembat (1862-1922), likewise received a ministry. Over the long term, the most important appointment went to the leader of the "reformist" wing of the Socialist party, Albert Thomas (1898-1966). He became head of the “State Secretariat for Artillery and Military Equipment,” then, at the end of October 1915, Minister of Armaments (Ministre de l’armement et des fabrications de guerre). On the other hand, appointing representatives of the extreme nationalists and Catholic groups on the right was initially not an option. Only in 1915 was a Catholic politician, Denys Cochin (1851-1922), sworn in as minister of state. Nevertheless, the Union sacrée always retained its secular character at the ministerial level and did not drift into rightist nationalism. In reality, it was only a domestic political truce ("trêve"), while attempts during the emergency to forge lasting social reform – in whatever direction – were unsuccessful. This was especially true of efforts on the right to undermine the foundations of the republic, particularly its secularism and the exclusion of the anti-Republican Right from governing coalitions.[30]

In the constitutional monarchy of Imperial Germany, on the other hand, such a demonstration of parliamentary solidarity was impossible. The inclusion of a "red" in the government remained inconceivable on all sides.

In principle, then, the "Spirit of 1914" was at the outset less a political development than a solemn mood. It grew out of a sense of astonishment that it should now be possible, in the face of the fatherland’s potential destruction, to be a "nation of brothers," which transcended traditional class divisions, bitter political conflicts, and the general abuse of "enemies of the Reich" of many categories.

Ideologization of the "Burgfrieden"↑

Patriotic unity could only momentarily conceal the social and political fissures, however. From September 1914 on, the Pan-Germans published manifestos and articles in which they expressed their joy that all Germans had become Pan-Germans.[31] The conservatives, for their part, believed they could detect Germans’ overwhelming satisfaction with the monarchy, which meant that reform of the Prussian three-class franchise system was now obsolete. Meanwhile, the Social Democrats called for the political participation that had previously been denied to them, including democratic suffrage reform, recognition of the trade unions by the state, and, above all, constitutional reform. The chancellor’s responsibility to the parliament and the parliament’s right to legislative initiative were to be the foundations of this reform. Eduard David (1863-1930), a representative of the reformist or "opportunistic" right wing of the party, bluntly stated that "we expect democratic suffrage reform as the price of the working class’ war effort."[32]

From the outset, the government sought to use the "Burgfrieden" to bring about a kind of "reorientation" of the empire. However, as Bethmann Hollweg remarked in September 1914, these efforts were limited "to putting [Social Democracy] on a national and monarchical footing."[33] However, nothing concrete emerged in this direction.

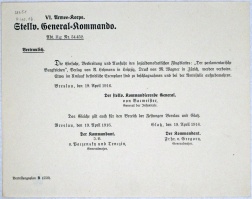

So the German "Burgfrieden" only masked political conflicts, and it remained a sham peace. The "deputy general commands" (Stellvertretende Generalkommandos), which were occupied by soldiers and were alone responsible for the censorship of the press in Germany, tended not to limit the expression of conservative opinion while they blocked leftist publications.[34]

As Steffen Bruendel has shown, there were many efforts after October 1914 to exploit the "Burgfrieden," which remained in force only as long as the war continued, for far-reaching social restructuring. Intellectuals of all political persuasions, especially those in the National-Liberal camp, were fascinated by the idea that the experience of national unity and the "enthusiastic" commitment to common defense could give rise to a new society. The historian Friedrich Meinecke (1862-1954), who was already known as an outstanding mediator between historical scholarship and political science, argued in his volume of essays "Die deutsche Erhebung" ("The German Uprising")[35] in October 1914 that the "August Experience" and the unity of all Germans against the external enemy would lead to a new community of the entire nation. Divided German society would, according to Meinecke, be transformed into a new commonality of the nation, as individual interests retreated in favor of the whole - a vision for which the concept of the "Volksgemeinschaft" (national community) was invoked, after moderate Social Democrats first used it.[36]

Nonetheless, the view was also common that the truce could be but a temporary response to the plight of the fatherland. In his speech to the Reichstag on 4 August, Bethmann Hollweg had nothing to say about the possible long-term consequences of a "national community" or anything like it. And even the emperor’s proclamations referred to keeping conflicts at bay during a short war, which all assumed would be over by Christmas 1914.[37]

It has not been sufficiently appreciated that calls to transform the “Burgfrieden” into a new kind of society were significantly accentuated by developments in August and September 1914. Georges-Henri Soutou has noted that Wilhelm II’s August proclamation assumed a kind of "heroic isolation" for Germany, while Poincaré’s remarks about the Union sacrée alluded immediately to the international community’s solidarity with beleaguered France, as well to the highest common values of all civilized nations.[38] In fact, at the outset of the war the Allies launched a steadily growing, multifaceted, and highly imaginative propaganda campaign against the German "barbarians, who acted 'like Huns'." Fueling this propaganda was the behavior of the German army. Its march through Belgium featured the mass shooting of alleged "guerillas" and brutal "retaliations," in which a number of Belgian and northern French towns were devastated and more than 6,000 civilians, including women and children, were massacred.[39] In addition, the Germans burned down the Cathedral in Reims and the University Library in Louvain, which the Allies and neutrals immediately portrayed as an act of cultural barbarism. Although the international public outcry against such acts could hardly be justified, German scholars, intellectuals, and artists attempted to do so. Ninety-three of them jointly published an appeal "To the Civilized World," which categorically rejected all the allegations of the Allied propaganda ("It is not true…"). Worse, in view of the atrocities that the German soldiers had undeniably - for whatever reason - committed in August and September, was the appeal’s claim that German culture could only have emerged and survived because “Prussian militarism" had protected it against foreign attack and would continue to do so.[40]

The now infamous "Aufruf der 93" (Manifesto of the Ninety-Three) should be seen as an unsuccessful attempt to create a kind of “Burgfrieden” en miniature, a united front of German intellectuals. The signatories represented anything but a politically homogeneous group. They included men of all confessions and political creeds (except Social Democrats), who, under normal circumstances, feuded bitterly or had nothing to do with one another. Many of them had not even read the appeal but signed it anyway, in order to signal that the German intellectual elite was itself unified in the "struggle for existence" and the preservation of "German culture."

In any case, after mid-1915 the “Burgfrieden” and national community were hardly discussed. Apart from fundraising campaigns on behalf of war bonds, which featured the nailing of wooden statues (like the "Iron Hindenburg" in Berlin), there was hardly a sign of these high-minded concepts.[41] The restraint of the war’s first days gave way to fierce debate about "war aims." The debate began with the "associations’ memorandum" in March 1915, and it became increasingly intense during the following months, particularly once the government and the military censors permitted the publication of annexationist demands while forbidding demonstrations in favor of a negotiated peace.[42]

By 1916 at the latest, the war had become a gloomy and troublesome ordeal for the Germans. The fronts lay far from home and the idea of a "defensive war" had lost its appeal. In 1916, the prominent literary critic Walther Hollander (1892-1973) wrote:

At the end of 1916, the industrialization of the "Great War" reached a new level with the implementation of the so-called "Hindenburg Program." This program was possible only because the strike-ready workers and their unions had for the first time been granted a voice in the workplace. Germany thus remained a "class society at war,"[44] which failed to preserve the “Burgfrieden” during an increasingly total war and to cope collectively with the war’s challenges.

Or, alternatively, was this banalizing of war in Germany itself a kind of extension of the “Burgfrieden” of 1914? Was it a continuation of the old slogan of the Prussian monarchy that in wartime "the citizen's first duty is keep calm"?[45] In any event, the main difference between the Union sacrée and the “Burgfrieden” lay in the fact that the French actually fought a defensive war, which they had to wage collectively as long as the enemy was in their country. This is why various efforts to exploit the wartime state of emergency to bring about basic political changes in France could have no lasting success. Conversely, the German fiction of a defensive war, which the German Reich then propagated around the world, was itself unsuited to founding an enduring sacred union of the nation.

Conclusion↑

The French-German comparison shows that the mood at the beginning of the war was similar in the two countries. In both, the war was overwhelmingly interpreted as a defensive conflict, forced on the country by external enemies. The two countries met this challenge with comparable resolve. The so-called "war enthusiasm" remained a marginal phenomenon. However, the discourse of defensive war was stronger and more durable in France, for the Germans actually had invaded. As a consequence the “Burgfrieden” became more ideologized in Germany than in France, where the Union sacrée could never be more than a pragmatic rallying of forces against the German invader.

Gerd Krumeich, Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf

Section Editor: Roger Chickering

Translator: Christopher Reid

Notes

- ↑ See Fiechter, Jean-Jacques: Les socialismes français et allemand et le problème de la guerre, Lausanne 1958; See also Krumeich, Gerd: Les Sociaux-Démocrates allemands et la conception jaurésienne de la Défense Nationale, in: Jaurès et la Défense Nationale. Actes du colloque de Paris, 22 et 23 Octobre 1991, in: Cahiers Jaurès 3, pp. 115-126.

- ↑ See esp. Jung, Werner: August Bebel, deutscher Patriot und internationaler Sozialist. Seine Stellung zu Patriotismus u. Internationalismus, Pfaffenweiler 1988, pp. 288-289.

- ↑ "Wie sollen, wenn Krieg kommt, die Sozialdemokraten behandelt werden? Sich sofort ihrer versichern, selbst und menschlich mit ihnen verhandeln, von den Militärs Garantien gegen die Dummheiten uniformierter Socialistenfresser geben lassen. Der Kanzler will dies thun, (…) Verteidigungskrieg betonen." Erdmann, Karl-Dietrich (ed.): Kurt Riezler. Tagebücher, Aufsätze, Dokumente, Göttingen 1973 (new edition 2008), pp. 189-190, incl. footnotes.

- ↑ "Morgen sollte socialdemokratische Demonstration für den Frieden sein. Wäre verhängnisvoll (…) Natürlich giebt es wieder Generale, die gleich eingreifen und schießen und es 'den Roten zeigen' wollen. (…) Gott sei Dank hat der Kanzler energisch eingegriffen. Im Übrigen werden die Sozialdemokraten von allen Seiten bearbeitet." Ibid. pp. 192-193, incl. footnotes 8 and 9 on specific forms of “bullying” by the government; for the maneuvering of the SPD leadership, see also: Kruse, Wolfgang: Krieg und nationale Integration. Eine Neuinterpretation des sozialdemokratischen Burgfriedensschlusses 1914/15, Essen 1994; still of great documentary value is: Kuczynski, Jürgen: Der Ausbruch des Ersten Weltkrieges und die deutsche Sozialdemokratie. Chronik und Analyse, Berlin (East) 1957; Miller, Susanne: Burgfrieden und Klassenkampf. Die deutsche Sozialdemokratie im Ersten Weltkrieg, Düsseldorf 1974, pp. 37-44.

- ↑ "La France ayant fait tout ce qui dépendait d'elle pour garder la paix (…) Il était indispensable que l'Allemagne, qui avait toute la responsabilité de l'agression, fût amenée à avouer publiquement ses intérêts. S'il avait fallu déclarer la guerre nous-mêmes, (…) c'était l´élan national brisé (…)." Cited from: Krumeich, Gerd: Juli 14. Eine Bilanz, Paderborn 2014, p. 178.

- ↑ See: Ritter, Gerhard: Der Schlieffenplan. Kritik eines Mythos, Munich 1956; the most recent research: Ehlert, Hans et al. (eds.): Der Schlieffenplan. Analysen und Dokumente, Paderborn 2006; also noteworthy is the study: Hénin, Pierre-Yves: Le Plan Schlieffen: Un mois de guerre – deux siècles de controverses, Paris 2012.

- ↑ "Meine Herren, wir sind jetzt in der Notwehr (lebhafte Zustimmung) und Not kennt kein Gebot! (Stürmischer Beifall). Unsere Truppen haben Luxemburg besetzt, vielleicht schon belgisches Gebiet betreten. Meine Herren, das widerspricht den Geboten des Völkerrechts. (…) Das Unrecht – ich spreche offen – das Unrecht, das wir damit tun, werden wir wieder gutzumachen suchen, sobald unser militärisches Ziel erreicht ist. Wer so bedroht ist wie wir und um sein Höchstes kämpft, der darf nur daran denken, wie er sich durchhaut." Cited from: Hirschfeld, Gerhard/ Krumeich, Gerd: Deutschland im Ersten Weltkrieg, Frankfurt 2014, p. 58.

- ↑ "Zum Zeichen dessen, daß Sie fest entschlossen sind, ohne Parteiunterschied, ohne Standes- und Konfessionsunterschied mit mir durch dick und dünn, durch Not und Tod zu gehen, fordere ich die Vorstände der Parteien auf, vorzutreten und mir dies in die Hand zu geloben." As indicated in Purlitz, Friedrich Wilhelm et al. (eds.): Deutscher Geschichtskalender, volume 2, Leipzig 1914, p. 47. The description of the Reichstag session is based on this source.

- ↑ The following sources offer a highly vivid impression of this internal dispute and the inability during that time to evade the "Burgfrieden": Matthias, Erich and Pikart, Eberhard (eds.): Die Reichstagsfraktion der deutschen Sozialdemokratie 1898 bis 1918, Part 2, Düsseldorf 1966, p. 3ff: Minutes of faction meetings from 3-4 August 1914; Matthias, Erich and Miller, Susanne (eds.): Das Kriegstagebuch des Reichstagsabgeordneten Eduard David 1914 bis 1918, Düsseldorf 1966, pp. 3-13; see also the subsequent (1919) report from Karl Liebknecht on the meeting of the fraction from 3 August 1914, in.: Dokumente und Materialien zur Geschichte der deutschen Arbeiterbewegung, vol. 1, Berlin 1958, pp. 19-21.

- ↑ Thus the well-founded reasoning of Miller, Susanne: Burgfrieden and Klassenkampf, Düsseldorf 1974, p. 68.

- ↑ See Bethmann Hollweg, Theobald von: Betrachtungen zum Weltkrieg, volume 1, Berlin 1919, p. 180.

- ↑ "(…) Mitten im Frieden überfällt uns der Feind. Nun auf zu den Waffen! Jedes Schwanken, jedes Zögern wäre Verrat am Vaterland! Um Sein oder Nichtsein unseres Reiches handelt es sich, das unsere Väter sich neu gründeten, um Sein oder Nichtsein deutscher Macht und deutschen Wesens. Wir werden uns wehren bis zum letzten Hauch von Mann und Roß. Und wir werden diesen Kampf bestehen, auch gegen eine Welt von Feinden. Noch nie war Deutschland überwunden, wenn es einig war. Vorwärts mit Gott, der mit uns sein wird, wie er mit den Vätern war!" Chronik des deutschen Krieges, Munich 1914, pp. 76-77; Variants of the speech, esp. the speech from 4 August in Berlin City Palace, in: Schulthess: Der europäische Krieg, p. 46ff.; ibid. pp. 52-53; Reichstag speech of Social Democrat representative Haase: "Wir lassen in der Stunde der Gefahr das Vaterland nicht im Stich." The above-cited imperial address from 6 August 1914 was repeated by Wilhelm II and preserved on a phonograph cylinder. See: Bundeskritik: Kaiser Wilhelm II. Aufruf an das deutsche Volk, online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0j_SlC8Ppx4 (retrieved: 5 May 2016).

- ↑ "Militärischen Wert hatte eine Burg nur, wenn ihre Besatzung friedlich zusammenlebte." Lexikon des Mittelalters, volume 2, Stuttgart 1999, p. 970.

- ↑ Bruendel, Steffen: Volksgemeinschaft oder Volksstaat. Die “Ideen von 1914” und die Neuordnung Deutschlands im Ersten Weltkrieg, Berlin 2003; Bruendel, Steffen: Solidaritätsformel oder politisches Ordnungsmodell? Vom Burgfrieden zur Volksgemeinschaft in Deutschland 1914-1918, in: Pyta, Wolfram/Kretschmann, Carsten (eds.): Burgfrieden und Union sacrée, Munich 2011, pp. 33-50; on the significance of the “Spirit of 1914” for the Nazi ideology of a Volksgemeinschaft, see: Fritzsche, Peter: Wie aus Deutschen Nazis wurden, Berlin 2001; Weinrich, Arndt: “Miracle d‘unité” et “enthousiasme de mobilisation”. L‘Allemagne et l‘Autriche entrent en guerre, in: Beaupré, Nicolas/Jones, Heather/Rasmussen, Anne (eds.): Dans la Guerre 1914-1918. Accepter, endurer, refuser, Paris 2015, pp. 55-80.

- ↑ For a general discussion, see: Raithel, Thomas: Das “Wunder” der inneren Einheit. Studien zur deutschen und französischen Öffentlichkeit bei Beginn des Ersten Weltkrieges, Bonn 1996.

- ↑ Krumeich, Gerd: Aufrüstung und Innenpolitik in Frankreich vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg, Wiesbaden 1980; Marcobelli, Elisa: La loi de trois ans et les socialistes français, Paris 2013.

- ↑ La Lanterne, 29 July 1914, issued by Gallica, online: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k7517248k.item (retrieved: 10 August 2016). This according to: Geiss, Peter: Französische Zeitungen in der Julikrise 1914, in: Geiss, Peter et al. (eds.): Die Presse in der Julikrise 1914, Münster 2014, pp. 83-112, here p. 106; for further reactions from the press, see: Raithel, Das Wunder 1996, pp. 193-202.

- ↑ For a comprehensive discussion, see: Becker, Jean-Jacques: Le Carnet B. Les pouvoirs publics et l'antimilitarisme avant la guerre de 1914, Paris 1973; also at length: Becker, Jean-Jacques: 1914. Comment les Français sont entrés dans la guerre, Paris 1977, which discusses the question of whether this arrangement was made at the request of local prefects and sub-prefects (from 31 July (!)).

- ↑ "(…) Avant d'aller vers le grand massacre, au nom des travailleurs qui sont partis, au nom de ceux qui vont partir et dont je suis, je crie devant ce cercueil toute notre haine de l'impérialisme et du militarisme sauvage qui déchainent l'horrible crime." Humanité, 5 August 1914, p. 1, cited in: Becker, Jean-Jacques/Krumeich, Gerd: Der Große Krieg. Deutschland und Frankreich im Ersten Weltkrieg, Essen 2008, p. 80; a detailled account of the funeral of Jaurès and the reaction to Jouhaux‘ speech in: Becker, 1914. Comment les Français 1977, p. 400ff.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 400.

- ↑ See Poincaré, Raymond: L’Union Sacrée 1914, in: Idem, Au service de la France, volume 4, Paris 1927, p. 508; Hoffmann, Michael: Die französischen Katholiken und der Erste Weltkrieg. Die Rückkehr aus der Sondergesellschaft, in: Pyta and Kretschmann (eds.), Burgfrieden und Union sacrée 2011, pp. 85-108, here esp. pp. 89-90.

- ↑ The "Message présidentiel" in the constitution of the 3rd Republic was the only manner in which the president could address both chambers and the public.

- ↑ "Dans la guerre qui s'engage, la France aura pour elle le droit, dont les peuples, non plus que les individus, ne sauraient impunément méconnaitre l'éternelle puissance morale. Elle sera héroïquement défendue par tous ses fils, dont rien ne brisera devant l'ennemi l'union sacrée et qui sont aujourd'hui fraternellement assemblés dans une même indignation contre l'agresseur et dans une même foi patriotique." Poincaré, L’Union Sacrée 1914, p. 546.

- ↑ For an illustrative example, see: Berliner Geschichtswerkstatt (ed.): 1914. Ein Volk zieht in den Krieg, Berlin 1988.

- ↑ Verhey, Jeffrey: Der “Geist von 1914” und die Erfindung der Volksgemeinschaft, Hamburg 2000, chapter 3; Geinitz, Christian: Kriegsfurcht und Kampfbereitschaft. Das Augusterlebnis in Freiburg. Eine Studie zum Kriegsbeginn 1914; Geinitz, Christian/Uta Hinz: Das Augusterlebnis in Südbaden. Ambivalente Reaktionen der deutschen Öffentlichkeit auf den Kriegsbeginn 1914, issued by Clio Online, online: http://www.erster-weltkrieg.clio-online.de/_Rainbow/documents/Kriegserfahrungen/geinitz%20und%20hinz.pdf (retrieved 6 May 2016).

- ↑ "Wir packten das Gerät zusammen und beschlossen, unten im Dorfe einen Trunk zu tun. Vor dem Rathause sahen wir, daß der Mobilmachungsbefehl bereits angeschlagen war. Im Kruge war keine besondere Aufregung zu bemerken – dem niedersächsischen Bauern ist die Begeisterung fremd, die zähe Erdkraft ist sein eigentliches Element. (…) Am Ernst-August-Platz [Hannover] marschierte ein ausrückendes Regiment vorbei. Die Soldaten sangen, Frauen und Mädchen hatten sich in die Reihen gedrängt und sie mit Blumen geschmückt. Ich habe seitdem noch manche begeisterte Volksmenge gesehen, keine Begeisterung war so tief und mächtig wie an jenem Tag." Jünger, Ernst: Kriegsausbruch 1914, in: Jünger, Ernst: Tagebücher I, Stuttgart 1978, pp. 542-543 ( = Sämtliche Werke, Abt. I, Tagebücher, Bd 1).

- ↑ "Die vorstehende Darstellung zeigt an den entscheidenden Tagen ein anderes Stimmungsbild als das, das von dem Enthusiasmus wogender Menschenmassen Unter den Linden und auf dem Schloßplatz allgemein verbreitet ist. Gewiss war auch der laute Enthusiasmus echt. Aber die unter ihm liegende Grundstimmung des deutschen Volkes in diesen Tagen war die eines schweren, ernsten Pflichtgefühls." Jastrow, Ignaz: Im Kriegszustand, Berlin 1914, p. 5.

- ↑ "…Heilig und rein war damals die Empfindung der deutschen Volksseele, wenige wußten, alle aber fühlten, daß dieser Krieg uns von den Feinden aufgezwungen war, daß er der Verteidigung der Heimat gegen die drohende Vernichtung galt (...). Weihevolle Stunden waren es, die wir alle in jenen ersten Augusttagen durchlebten, denn wir waren von der reinsten Pflichterfüllung getragen, von der Pflichterfüllung gegen Volk und Vaterland." Tänzer, Arnold: Kriegserinnerungen, in: Richarz, Monika (ed.): Jüdisches Leben in Deutschland, Stuttgart 1979, pp. 445-446.

- ↑ For an overview, see: Becker, 1914. Comment les Français 1977; Raithel, Das Wunder 1996, pp. 276-277, arrives at entirely similar findings, even if he is (overly) critical of Becker.

- ↑ On this topic in detail: Becker, Jean-Jacques: Union Sacrée et idéologie bourgeoise, in: Revue historique 535 (1980), pp. 65-74.

- ↑ Chickering, Roger: We Men Who Feel Most German. A Cultural Study of the Pan-German League 1886-1914, Boston 1984, pp. 290-291; Hering, Rainer: Konstruierte Nation. Der Alldeutsche Verband 1890-1939, Hamburg 2003, p. 240ff.

- ↑ "[dass] wir eine demokratische Reform des Wahlrechts als Preis für die Kriegsleistung der Arbeiterschaft erwarten." Wehler, Hans-Ulrich: Deutsche Gesellschaftsgeschichte, volume 4, Munich 2003, p. 45.

- ↑ See Gutsche, Willibald: Bethmann Hollweg und die Politik der “Neuorientierung, in: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft 13 (1965), p. 243; see also: Verhey, Der “Geist von 1914” 2000, chapter 3.

- ↑ On this topic, see especially Deist, Wilhelm (ed.): Militär und Innenpolitik im Weltkrieg 1914-1918, 2 volumes, Düsseldorf 1970, here: volume 1, chapter 2.

- ↑ See Meinecke, Friedrich: Die deutsche Erhebung von 1914. Vorträge und Aufsätze, Stuttgart/Berlin 1914, issued by the Internet Archive, online: https://archive.org/details/deutscheerhebung00mein (retrieved: 10 August 2016).

- ↑ Ibid.; Bruendel, Volksgemeinschaft oder Volksstaat 2003; Verhey, Der "Geist von 1914" 2000.

- ↑ For a summary: Krumeich, Gerd: Juli 1914. Eine Bilanz, Paderborn 2014.

- ↑ Soutou, Georges-Henri: Die Kriegsziele des Deutschen Reiches und der französischen Republik, in: Pyta and Kretschmann, Burgfrieden und Union sacrée 2011, pp. 51-70, here: pp. 52-53.

- ↑ On the "franctireur" war and the massacres in Belgium and northern France, see the study by Horne, John and Kramer, Alan: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914. Die umstrittene Wahrheit, Hamburg 2004; recent new research seems to bring up some criticism however, showing that there have indeed taken place a lot of civilian aggressions against German troups: Gunter Spraul, Der Franktireurkrieg 1914. Untersuchungen zum Verfall einer Wissenschaft und zum Umgang mit nationalen Mythen, Berlin 2016.

- ↑ See Ungern-Sternberg, Jürgen von/Ungern-Sternberg, Wolfgang von: Der Aufruf “An die Kulturwelt!”. Das Manifest der 93 und die Anfänge der Kriegspropaganda im Ersten Weltkrieg, Frankfurt 2013.

- ↑ For a summary, see: Schneider, Gerhard: In eiserner Zeit. Kriegswahrzeichen im Ersten Weltkrieg. Ein Katalog, Schwalbach/Ts 2013; Schneiders meticulous list of all known Nail Men shows that this actually began in mid-1915, in all likelihood to reinvigorate the flagging interest in the Burgfrieden.

- ↑ For all the memoranda, see: Grumbach, Salomon: Das annexionistische Deutschland. Eine Sammlung von Dokumenten, die seit dem 4. August 1914 in Deutschland öffentlich oder geheim verbreitet wurden, mit einem Anhang: Antiannexionistische Kundgebungen, Lausanne 1917 (Ndr. Biolife 2015); the Denkschrift der 6 Wirtschaftsverbände ibid. p. 1232ff.

- ↑ "Die Gewohnheit stumpft gegen das Schauspiel ab. Vor allem aber ist es, daß der Krieg der Akteure und ihres Anhangs immer größer wird und daß sich der Kreis der unbeteiligten Zuschauer erheblich verringert. (…) Es ist nichts Besonderes mehr in den Krieg zu gehen. Es begleiten nicht mehr Blumen und Zurufe den Scheidenden, es ist kaum mehr ein Achselzucken, wenn jemand fällt. Die Staffage versinkt, es ist gewöhnlicher Alltag, was drinnen und draußen gelitten wird." Quoted in: Müller, Hans-Harald: Der Krieg und die Schriftsteller, Stuttgart/Munich 1986 p. 19.

- ↑ Hence the title of the seminal book by Kocka, Jürgen: Klassengesellschaft im Krieg. Deutsche Sozialgeschichte 1914-1918, Göttingen 1973.

- ↑ It is not surprising that the similar appeal from the governor of Berlin after the defeat of Jena and Auerstett in 1806 became a popular dictum.

Selected Bibliography

- Becker, Jean-Jacques: Union sacrée et idéologie bourgeoise, in: Revue Historique 264/1, 1980, pp. 65-74.

- Becker, Jean-Jacques: 1914. Comment les Français sont entrés dans la guerre. Contribution à l'étude de l'opinion publique printemps-été 1914, Paris 1977: Presses de la Fondation nationale des sciences politiques.

- Becker, Jean-Jacques / Krumeich, Gerd: Der Große Krieg. Deutschland und Frankreich im Ersten Weltkrieg 1914-1918, Essen 2010: Klartext.

- Berliner Geschichtswerkstatt: August 1914. Ein Volk zieht in den Krieg, Berlin 1989: Nishen.

- Bruendel, Steffen: Volksgemeinschaft oder Volksstaat. Die 'Ideen von 1914' und die Neuordnung Deutschlands im Ersten Weltkrieg, Berlin 2003: Akademie Verlag.

- Bruendel, Steffen: Solidaritätsformel oder politisches Ordnungskonzept? Vom Burgfrieden zur Volksgemeinschaftsidee in Deutschland 1914-1918, in: Pyta, Wolfram / Kretschmann, Carsten (eds.): Burgfrieden und Union sacrée, Munich 2011: Oldenbourg, pp. 33-50.

- Geinitz, Christian: Kriegsfurcht und Kampfbereitschaft. Das Augusterlebnis in Freiburg. Eine Studie zum Kriegsbeginn 1914, Essen 1998: Klartext.

- Krumeich, Gerd: Juli 1914. Eine Bilanz, Paderborn 2014: Ferdinand Schöningh.

- Kruse, Wolfgang: Krieg und nationale Integration. Eine Neuinterpretation des sozialdemokratischen Burgfriedensschlusses 1914/15, Essen 1993: Kartext Verlag.

- Kuczynski, Jürgen: Der Ausbruch des Ersten Weltkrieges und die deutsche Sozialdemokratie. Chronik und Analyse, Berlin 1957: Akademie-Verlag.

- Miller, Susanne: Burgfrieden und Klassenkampf. Die deutsche Sozialdemokratie im Ersten Weltkrieg, Düsseldorf 1974: Droste.

- Pyta, Wolfram / Kretschmann, Carsten (eds.): Burgfrieden und Union sacrée. Literarische Deutungen und politische Ordnungsvorstellungen in Deutschland und Frankreich, 1914-1933, Munich 2011: Oldenbourg.

- Raithel, Thomas: Das 'Wunder' der inneren Einheit. Studien zur deutschen und französischen Öffentlichkeit bei Beginn des Ersten Weltkrieges, Bonn 1996: Bouvier.

- Steinbach, Matthias: Mobilmachung 1914. Ein literarisches Echolot, Stuttgart 2014: Reclam.

- Ungern-Sternberg, Jürgen von / Ungern-Sternberg, Wolfgang von: Der Aufruf 'An die Kulturwelt!' Das Manifest der 93 und die Anfänge der Kriegspropaganda im Ersten Weltkrieg (2 ed.), Frankfurt a. M. 2013: Lang-Ed..

- Verhey, Jeffrey: Der 'Geist von 1914' und die Erfindung der Volksgemeinschaft, Hamburg 2000: Hamburger Edition.

- Weinrich, Arndt: Miracle d'unité et enthousiasme de mobilisation. L'Allemagne et l'Autriche entrent en guerre, in: Beaupré, Nicolas / Jones, Heather / Rasmussen, Anne (eds.): Dans la guerre 1914-1918. Accepter, endurer, refuser, Paris 2015: Les Belles Lettres, pp. 55-80.