The Invasions of Germany, 1914-1915↑

While imperial Germany’s aggression and occupation practices during the First World War have been carefully studied, historians have devoted far less attention to the country’s own experiences of being invaded and occupied. The Reich was, albeit much less severely than other continental powers, invaded early in hostilities. In the west, the French army advanced into Alsace-Lorraine in mid-August 1914. It was ejected a week later, holding only a small and unimportant border strip throughout the conflict. The Russian army’s assaults on East Prussia, Germany’s most north-easterly province, were more serious. Two invasions took place from August to September 1914 and from November 1914 to February 1915, and only in March 1915 were the last tsarist troops, men from a raiding force which had briefly occupied the town of Memel (today Klaipėda), evicted from German soil. These attacks, although now forgotten, entailed heavy fighting, caused much civilian suffering, and made a powerful impression on Germans. They appeared to confirm the government’s claim that the Reich had been forced into a righteous war of defence. The German public was shocked by floods of refugees and stories of vicious atrocities committed by enemy armies. The invasions were a national trauma, which shaped popular understanding of why the conflict had to be fought and contributed to mobilising Germans for war.

Invasions and “Atrocities”, August – September 1914↑

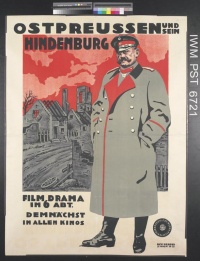

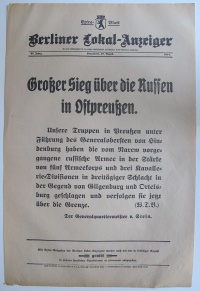

The First World War began with offensives on all fronts. The German army’s lightning attack through Belgium and into northern France, which was designed to encircle and defeat the Republic’s army within six weeks, is only the most infamous. The French and Russian armies too began the conflict with coordinated strategies of attack. The French opened their campaign with a short assault by one corps into Alsace on 7 August, and one week later two French armies advanced into Alsace and Lorraine with the aim of disrupting the German offensive further north. In the east, the Russians launched a simultaneous assault with two armies on East Prussia, which was intended to draw off German strength from the Western Front and capture the province, opening the way for an invasion into the Reich. Both plans failed. The French met strong, entrenched forces and were quickly repulsed. The Russians, although they posed a threat sufficient to cause two German corps to be transferred from the Western to the Eastern Front, were also defeated. One of their invading armies was famously encircled and destroyed by a German force under General Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934) at Tannenberg in the last days of August. These defenders then expelled the other army from East Prussia by mid-September. Germany thus avoided decisive defeat and deep invasion in 1914.[1]

For the Reich’s population, this was extremely fortunate, for the relatively small areas which fell under enemy occupation suffered not only through the fighting but also from “atrocities” perpetrated by enemy soldiers. Contemporary international law, as laid down in the 1907 Hague Convention, imposed a number of obligations on invading forces, including the protection of populations’ lives and property, and prohibited collective punishments and the attack and bombardment of “undefended” places. In neither east nor west were these rules consistently followed by soldiers or commanders. The Russian army’s conduct during its August and September 1914 attack on Germany has been most thoroughly researched. While historians once believed that the “Cossack terror” was a myth, recent studies have found evidence of considerable violence against civilians.[2] The tsar’s army killed 1,500 non-combatants during its invasions of East Prussia, the vast majority in this early campaign. The bloodshed was equivalent to that perpetrated at around the same time by the German military against Belgian and French civilians: fatalities were, proportionate to the size of the invasion zones’ populations, identical.[3] Other forms of violence and repression, including hostage-taking, curfews and “contributions” (collective fines on towns), also seen in the west, were used by the Russian military in East Prussia. Although it was forbidden and they were punished severely when caught, tsarist troops looted widely and committed hundreds of rapes. Horrendous physical destruction was suffered by the province. 41,414 buildings were demolished and another 60,000 damaged, most in fighting, but some through deliberate punishments and reprisals. Overall, three-fifths of the province’s small towns and a quarter of its villages and farms were partially or totally ruined.[4]

The French army’s invasion of Alsace-Lorraine in August 1914 is far less well-studied. The province’s inhabitants certainly suffered violence at the hands of the German army, which believed them to be traitorously taking part in the fighting.[5] Recently, however, indications that the French military may also have fought the campaign less than cleanly have come to light. There were units which massacred civilians considered suspicious or treacherous, although how typical such brutality was is still unclear due to lack of research. A French War Ministry order of 22 August 1914 instructing troops to conduct arrests and deportations has survived, indicating that higher authorities were prepared to sanction some actions of dubious legality.[6] German authorities subsequently found that many state, community and church officials had been taken hostage and estimated that over 3,000 women, children, youths and old men were deported or evacuated from Alsace-Lorraine during the war. The French army was accused – whether justifiably or not is unclear – of what amounted to ethnic cleansing; a deliberate attempt to weed out pro-Reich elements from an indigenous populace that was assumed to be naturally Francophile.[7]

The violence and repression on Germany’s eastern and western borders was motivated by four interrelated factors. First, armies embarked on their campaigns primed to meet civilian resistance. The Russian military used ethnicity as a marker for reliability and its peacetime studies predicted German civilians’ hostility.[8] The French army expected the Alsace-Lorraine population to be friendly, but feared pro-German elements in the province. Second, on both fronts, fluid and bloody fighting disorientated troops and appeared to confirm these expectations. Unable to see camouflaged enemies armed with smokeless munitions, soldiers frequently assumed that inhabitants were ambushing them, spying or guiding opponents’ fire. These delusions became especially acute in military crises such as the Russians’ September retreat. Third, poor discipline not only made conscripts vulnerable to panic but, at least in East Prussia, also helps to account for plundering and sexual assaults. Finally, although the violence began with troops lashing out and junior and middle-ranking officers ordering bloody reprisals, the repression was later sanctioned by higher commands, despite its illegality.[9] The French War Ministry’s deportation order offers one example. The Russian commander-in-chief, Nikolai Nikolaevich, Grand Duke of Russia (1856–1929), was even more ruthless in East Prussia, ordering, on 2 September, that “complete destruction” should befall habitations whose populations shot at his men.[10]

Occupation and Deportations, November 1914 – February 1915↑

The invasions at the war’s opening brought German territory under enemy control for at most a few weeks. The Russian army’s second invasion of East Prussia in November 1914, by contrast, resulted in an occupation of the easterly fifth of the province for three and a half months. The tsarist military administered the conquered territory directly, and, unlike in August and September, did not use East Prussian officials or appoint German civilians to assist. Most inhabitants were evacuated before the invasion. Probably fewer than 40,000 remained.[11] The tsarist army gave them food and medical care and, as during the summer, punished soldiers caught stealing or raping. Nonetheless, conditions during the occupation were harsh. Inhabitants were carefully controlled, in some cases forced to move domicile and had their property requisitioned. The territory was looted, not just by individual soldiers but systematically and thoroughly by Russian military commanders.[12]

The worst aspect of the occupation was the mass deportations. These were not wholly novel: in the summer invasion, the Russians had arrested thousands of men of military age. Some had been held because they were suspected of resisting the invaders, others were drafted with their carts to assist the force’s supply columns and many had been taken simply to deny manpower to the opposing army. However, in the winter of 1914-1915, the deportations were far more extensive. By one official estimate, over 30 percent of inhabitants still present in the north and centre of the occupation zone were removed.[13] In some places, the Russians again took only military-aged men but frequently they forced entire communities, including 4,000 women and 2,500 children, into the interior of the tsar’s empire. These deportations were part of larger population movements motivated by military security paranoia that took place simultaneously in Russia’s war zones and western provinces. Jews in Galicia and the Pale of Settlement and Muslims on the Caucasian Front were forcibly removed. Most notably, at around the same time as the deportations from East Prussia began, Russia’s own ethnic Germans were also transferred eastwards by the army.[14] Most East Prussian deportees were transported in terrible conditions, without adequate food or heating. Even in their places of internment on the Volga, or between the Volga and the Urals, survival was difficult. More than 13,000 East Prussians were deported by the Russians in 1914-1915, of whom over 4,000, around one-third of the total, died.[15]

Aftermath: Meaning and Memory↑

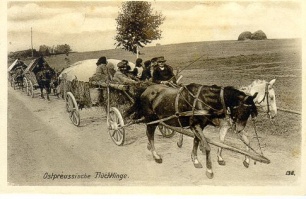

The invasions of 1914-1915 shocked Germany’s population. Stories, true and exaggerated, of the violence perpetrated by the Russian army in particular circulated the Reich from late August 1914. They were disseminated through three channels. Refugees were one important source. In the first invasion, 800,000 East Prussians were displaced, tens of thousands of whom travelled across the Vistula into the interior of Germany. At the start of the second attack, 250,000 East Prussian civilians and tens of thousands of military-aged men from other eastern provinces were evacuated and dispersed across the country.[16] Soldiers in the war zone, many of whom came from outside the province, also circulated real and imagined atrocity accounts. Newspapers too were influential, reporting extensively and largely accurately on tsarist troops’ conduct in occupied territories. The invasions, although they directly affected only a small part of Reich territory, were widely understood as violations of the entire nation, and generated powerful emotions of fear, outrage and national solidarity. The close identification felt in the country for the plight of the province and its peoples was expressed in the success of the “Ostpreußenhilfe” (“East Prussia Aid”) charity appeal, which collected over 12 million marks.[17]

The invasions’ impact on Germany was profound. The memories and myths that surrounded them helped to shape the national war effort. The Russians’ “atrocities” were exploited by official propaganda throughout hostilities as a warning of the horror that defeat could bring and proof of the need to hold out.[18] The gratitude felt by Germans to the victor of Tannenberg, Paul von Hindenburg, for “saving” the nation in 1914 laid the foundations for a personality cult that ultimately propelled this soldier to the leadership of Germany’s war effort in 1916-1918 and to the presidency of the Weimar Republic in 1925-1934.[19] For East Prussia, the invasions were a seminal moment of integration into the Reich. The solidarity that Germans displayed to this distant province was repaid during the 1920 plebiscite in its Polish dialect-speaking Masurian south, when 98 percent of votes cast rejected the option to join the newly established Poland. The memory of the invasions remained potent in the province throughout the inter-war period. Only with another invasion of far greater brutality in the Second World War, and the destruction of East Prussia itself, did the suffering of 1914-1918 disappear into obscurity.[20]

Occupation of the Rhineland and Ruhrgebiet (1918-1930)↑

For many years, the history of military occupations in the Rhine and Ruhr areas after 1918 was mostly understood in the context of the Franco-German reparations dispute and French foreign and security policy. Up until the 1950s, distinctly national points of view regarding the Versailles post-war order and the Allied reparations policy predominated. The German side mainly recognized "Versailles" as a synonym for ruthless French power politics, which had done irreparable harm to the young republic. From the French perspective, "Versailles" chiefly represented the failure of a sustainable security policy. Against the backdrop of the even greater catastrophe of the Second World War, the prevailing opinion was that even though the negotiated peace treaty was painful for Germany, it was nonetheless in the end a bearable compromise which offered plenty of room for the country’s successful and peaceful development. It was conceded that the former "peace makers" very likely had little chance to maneuver given the enormous upheavals and turmoil that had been caused by the First World War.[21] In opposition to this still-predominant interpretation – which primarily aims to work out the opportunities that the Versailles post-war order presented despite all the obstacles – a new perspective has recently emerged. It places the hitherto largely ignored military occupation policy itself and the confrontations between the population in the occupied territories and the occupiers in the foreground. Moreover, it investigates the dispositions of the former protagonists, which effectively hindered the former enemies’ reconciliation. This approach not only concludes that the war in many respects persisted in the minds of the inhabitants of the Allied-occupied Rhineland and the Ruhr areas. It also finds that the occupation experience of the French and the Belgians during the war was decisive in shaping occupation policy.[22] On the German side, the occupation was perceived as a national disgrace. What is more, it promoted German nationalism and strengthened the desire for a revision (even by force) of the Versailles post-war order, especially in the manner advocated by the Nazis.[23]

Rhine Frontier, French Security Policy, and the Treaty of Versailles↑

Earlier French efforts to establish the Rhine as a future military frontier of Germany were increasingly stifled after the military defeat in 1870. However, following the outbreak of the First World War, the demand to strip the areas west of the Rhine from the (generally thought to be harmful) influence of Prussia found new advocates, particularly among France’s military and political leadership. Opinions nonetheless differed widely as to just how the "Rhineland question" should be solved, whether, for instance, in the form of annexation, neutralization, the creation of an autonomous region, or a permanent military occupation. The French commander, Ferdinand Foch (1851-1929) pointed out the need to occupy the left bank of the Rhine to Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929) in October 1918. He demanded that the Rhine first be established as the western border of Germany and then, at a minimum, as a military frontier. France’s uncompromising demands, however, were met with resistance from Great Britain and the USA.

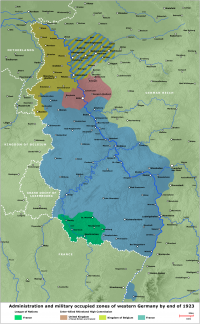

In the ceasefire agreement from 11 November 1918, the settlement of the Rhineland question was set aside. It merely provided for the Allied occupation of the left bank of the Rhine and three "bridgeheads" near Cologne, Mainz, and Koblenz. The German troops were forced to withdraw behind a ten kilometer wide neutral zone along the right bank of the Rhine. During the negotiation of the Treaty of Versailles, France had to forgo any additional ideas it had in the Rhineland question and finally accept a compromise. To meet the French need for security, the US and Great Britain promised France military support in the event of a German attack. In return, the occupation of the Rhineland was limited to fifteen years. Four occupation zones were established, which were to be vacated by the Allied forces at different time intervals (i.e. five, ten, and fifteen years). The smallest zones were left to the British (Cologne and the surrounding districts) and the Americans (Koblenz and the surrounding districts), with the US surrendering its area to the French in 1923. A failure on the part of the German government to uphold its contractual obligations would result in an extension of the occupation. The goal of the occupation was, on the one hand, to achieve military protection against Germany, and, on the other, to secure collateral for the German reparations.[24]

Occupation Administration, Separatism, and “Peaceful Penetration”↑

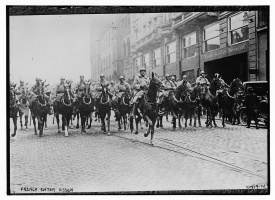

At the beginning of the occupation of the Rhineland, the French army alone had about 95,000 soldiers (including about 20,000 from its colonies). When the Treaty of Versailles came into force in January 1920, the initially purely military administration was replaced by an Allied civilian administration, the Haute Commission Interalliée of Territoires Rhénanes ("Inter-Allied Rhineland High Commission"). Its headquarters were located in Koblenz and it was led, until its dissolution in 1930, by Paul Tirard (1879-1945). Tirard was a top French official who had acquired considerable experience in building administrations in the Protectorate of Morocco and the recovered Alsace-Lorraine. In the High Commission, all occupying powers were represented by a commissioner. France, however, typically had the final say on matters. This was especially true once the US left the commission in 1923, and also given that the Belgian commissioner was usually in agreement with Tirard.[25]

During the purely military occupation, the generals attempted to exploit Francophile, separatist tendencies in the Rhineland and the Palatinate and thereby bring about a fait accompli. They did not succeed, however, as separatist tendencies were only weakly represented in the local population. Tirard, by contrast, pursued a policy of "peaceful penetration." France was to win over the population of the occupied territories by means of cultural events and a range of special benefits. The occupation soldiers were instructed to appear evenhanded and friendly towards the population. This policy, however, was repeatedly thwarted, whether it was because of aggressive behavior on the part of the occupiers, confrontations between the military and the civilian population, or German actions against the occupation authorities and individual soldiers. An ongoing point of contention was the use of colonial troops, which the Germans considered to be a provocation and especially demeaning. Children born from liaisons between German women and black occupation soldiers were discriminated against as “Rhineland bastards.” Nationalist racists saw them as a threat to the “white race,” while under the Nazi regime hundreds of young people were sterilized. During the French occupation, the arguments about the allegedly unique brutality of the colonial troops were expressed in the racist campaign against the so-called “black humiliation” (“Schwarze Schmach”).[26]

The Allied Occupation and the Reparations Dispute: The "Ruhr Uprising” of 1923↑

Tirard's policy of "peaceful penetration," however, was complicated by the escalation of the reparations dispute that began in 1921. This ultimately led to the military occupation of the industrial heart of Germany, the Ruhr Valley, in January 1923. The military occupation was used as leverage in the reparations dispute for the first time when the London Schedule of Payments (the “London ultimatum”) was established in the spring of 1921. To lend the Allies’ reparations demands additional weight, French troops occupied Düsseldorf and Duisburg on 8 March 1921. This development was followed by a week-long governmental crisis and civil unrest in Germany. To the conservative and right-wing opponents of the Weimar Republic, the German government’s acceptance of the London ultimatum in May 1921 was grist for the mill. It further legitimized the so-called “Dolchstoßlegende” (stab-in-the-back myth) and fueled propaganda concerning Germany’s innocence in the First World War.[27]

In the eyes of French politicians and military officials, the occupation of the Ruhr offered several advantages. Firstly, they saw the opportunity to finally force Germany to pay reparations. They also hoped to be able to enforce the aforementioned long-term plans to achieve permanent protection against Germany. The way for the occupation of the Ruhr was paved over the course of 1922. It was based on the French government’s conviction – which Raymond Poincaré (1860-1934) first put forward in January 1922 – that Germany had willfully delayed reparation payments, despite being at full productive capacity. When the new German Chancellor Wilhelm Cuno (1876-1933) clearly steered toward a collision course in November 1922, the French government decided to take action. On 26 December 1922, the Allied Reparations Commission determined that Germany was in arrears with its payments. Until Germany abandoned its delay tactics, the French government announced, the raw materials and industry of the Ruhr would serve the Allies as "productive collateral." To benefit from these forms of "collateral," a commission of French and Belgian engineers was sent to the Ruhr area on 11 January 1923 – along with 45,000 soldiers, who officially served as "protection." Within days, nearly the entire Ruhr valley was occupied. The number of occupation soldiers quickly rose to 100,000 men.[28]

The Shadow of World War: Passive Resistance, Violence, and Propaganda↑

Military resistance would have provoked an obvious escalation of the conflict. What’s more, it had no chance of success due to the actual balance of power. The German government therefore called on the population to take up "passive resistance." The occupiers were to be prevented from using the industrial area as "productive collateral." Whoever became unemployed from participating in the passive resistance would receive compensation from the government for the loss of income. This policy was mainly financed by the new money that Germany repeatedly put into circulation. At the same time, it also led to ever-increasing inflation and veritable hyperinflation.

Almost 32,000 civil servants (and almost 100,000 of their dependents) were expelled by the occupation authorities because they refused to cooperate with the “enemy.” Another focus of the passive resistance was the transportation blockade, which frustrated the occupying power’s desire to transport coal to France and Belgium. It was only able to get the idle railway into operation again with the help of its own engineers. Still, the strategy of passive resistance was not implemented everywhere. Some industrialists continued to produce or even collaborated with the occupiers. Others took advantage of the suspension of transportation to undertake long overdue repairs or repair work. This modernization formed the basis of the economic boom that occurred after 1924. The primary losers of the Ruhr occupation were the workers: real wages fell, and companies exploited the general crisis to suspend the rights that had been won in the November Revolution.[29]

There was also violent active resistance in the form of sabotage and assassination attempts. This was mostly driven by radical right-wing, nationalist groups, some of which were supported by the Reichswehr. French and Belgian troops responded with force, setting into motion a downward spiral of violence. Militant, right-wing groups also responded violently to German "collaborators," with the silent assent of the police. Some of these groups did not even shy away from carrying out lynchings.[30] Numerous "Ruhr fighters" were sentenced by the military courts of the occupying power. The most famous among them was the former First World War officer and Freikorps fighter Albert Leo Schlageter (1894-1923). He was sentenced by a French military court to death and shot on 26 May 1923. Schlageter was celebrated as a martyr by nationalist and conservative segments of the population. To many, he was the last casualty of the First World War. The Nazis later described their executed comrade as the "first fallen soldier of the Third Reich." Many of the militant nationalist "Ruhr fighters” would come together again later in the SA or the SS.

In general, the Rhineland occupation and the Ruhr struggle ("Ruhrkampf") signified the profoundly asymmetrical perceptions on both sides of the Rhine. The French government always emphasized the "peaceful nature" of the occupation. However, the militaristic parading of troops, the establishment of a well-functioning military administration, and the interventions into social and economic life in the occupied territory contradicted this assertion.[31] Again and again, clashes erupted between the occupiers and the occupied. According to contemporary estimates, by 1924 there were around 140 to 150 deaths among the civilian population in the occupied Ruhr and Rhineland.[32] Similarly to in 1914-1918, a propaganda war was ignited in which neither side sought to inquire objectively into specific cases, but rather only wanted to prove the legality of their own position. Here, the French side found itself, as “occupiers”, very much on the defensive before an international public. It also did not help that it referred in its propaganda to the hardly restrained occupation practices of the Germans in Belgium and northern France during the First World War. But the fronts had become entrenched and the deep-seated asymmetry in the perceptions of the two sides was not to be shaken.[33]

The End of the Rhineland and Ruhr Occupation↑

The confrontational policy of the Reich government, which was ousted in the summer of 1923, led Germany to the brink of disaster. Hyperinflation and social crisis, separatist impulses to secede in the occupied territory, and plans by the radical left and right to overthrow the government all endangered the existence of the young republic. Ultimately, the new government under Chancellor Gustav Stresemann (1878-1929) was compelled to end the ruinous showdown with the former wartime enemy on 26 September 1923. This initially led to another serious crisis, as the radical right took advantage of the widespread national outrage over the "surrender" to France to make a putsch attempt in November 1923. This first bid by the Nazis to seize power failed, however. Instead, the new Reich government managed to stabilize the economic and social situation. With the US taking a leading role, a comprehensive revision of the reparations was undertaken in 1924 with the Dawes Plan.

Nevertheless, the forced return to the negotiating table did not imply an immediate end to the occupation. French and Belgian troops withdrew from the Ruhr Valley in 1925. The remaining areas in the Rhineland were successively vacated in several stages and the French occupation was finally brought to a premature end on 30 June 1930. At the same time, the one party that had promised the most radical and aggressive revision of the Versailles post-war order – the National Socialists – achieved a decisive breakthrough. Immediately after gaining power in 1933, they began to prepare for their revenge. Accompanied by a massive propaganda effort, the Rhineland was remilitarized on 7 March 1936, foreshadowing the second “great war.”

Conclusion↑

Germany underwent violent and humiliating invasions and occupations both at the beginning and after the end of the First World War. The Russian attacks on East Prussia in 1914-1915 were bloody by contemporary standards, if not by those of the extraordinarily brutal totalitarian conflict fought three decades later between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. Executions, massacres, rapes and deportations were all perpetrated. The trauma of civilians in the war zone was transmitted across Germany by refugees, soldiers and newspapers. Widespread fear, rage and indignation resulted, which proved powerful in mobilising popular support for the war effort. A wave of solidarity swept the Reich, and, after 1918, lived on in the form of a closer bond between East Prussians and other Germans.

For many residents of the Rhineland, the Allied occupation was their first direct contact with enemy soldiers. Hostilities flared up time and again. While the extent of the violence was certainly not comparable to the occupations during the war, the conflicts – often exploited for propaganda purposes – nonetheless exacerbated the already tense relationship between France and Germany and stoked nationalist sentiments. When the tensions between the former enemies peaked in the Ruhr conflict in 1923, it was clear that the war was still ongoing – if only in the minds of those affected. Although it was possible to settle the differences of the two sides temporarily, the spirit of revenge remained alive and well in Germany.

Alexander Watson, Goldsmiths, University of London

Joachim Schröder, Hochschule Düsseldorf

Section Editor: Christoph Cornelißen

Translator: Christopher Reid

Notes

- ↑ See, for a good general account, Strachan, Hew: The First World War. To Arms, volume 1, Oxford 2001, pp. 212-216 and 307-335. The most detailed military history of the first Russian invasion of East Prussia remains Showalter, Dennis E.: Tannenberg. Clash of Empires, Hamden 1991.

- ↑ For early studies, see esp. Geiss, Imanuel: Die Kosaken kommen! Ostpreußen im August 1914, in: Geiss, Imanuel: Das Deutsche Reich und der Erste Weltkrieg, Munich and Vienna 1978; and Horne, John and Kramer, Alan: German Atrocities 1914. A History of Denial, New Haven and London 2001. Newer studies include Liulevičius, Vėjas Gabriel: Precursors and Precedents. Forced Migration in Northeastern Europe during the First World War, in: Nordost-Archiv. Zeitschrift für Regionalgeschichte. Neue Folge 14 (2005); Hoeres, Peter: Die Slawen. Perzeptionen des Kriegsgegners bei den Mittelmächten. Selbst- und Feindbild, in: Groß, Gerhard P. (ed.): Die vergessene Front. Der Osten 1914/15. Ereignis, Wirkung, Nachwirkung, Paderborn et al. 2006; and Watson, Alexander: Ring of Steel. Germany and Austria-Hungary at War, 1914-1918, London 2014. German official and semi-official histories written in the interwar period, notably Gause, Fritz: Die Russen in Ostpreußen 1914/15. Im Auftrage des Landeshauptmanns der Provinz Ostpreußen, Königsberg 1931; and Reichsarchiv: Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918. Die Befreiung Ostpreußens, volume 2, Berlin 1925 also provided extensive evidence for atrocities, but until very recently their results were dismissed.

- ↑ Watson, Ring of Steel 2014, p. 171.

- ↑ Ibid, pp. 170-181.

- ↑ Horne and Kramer, German Atrocities 2001, pp. 22, 106, 120-121.

- ↑ Becker, Jean-Jacques and Krumeich, Gerd: Der Grosse Krieg. Deutschland und Frankreich im Ersten Weltkrieg 1914-1918, Essen 2010, pp. 178-179.

- ↑ Bell, Johannes (ed.): Völkerrecht im Weltkrieg. Dritte Reihe im Werk des Untersuchungsausschusses, volume 1, Berlin 1927, pp. 161 and 167-169. See also Armeeoberkommando VII to Generalkommando XIV Reservekorps, 31 August 1914. Generallandesarchiv Karlsruhe, 465 F7 Nr. 165.

- ↑ See, for more details, Holquist, Peter: Les violences de l’armée russe à l’encontre des Juifs en 1915. Causes et limites, in: Horne, John (ed.): Vers la guerre totale. Le tournant de 1914-15, Paris 2010, pp. 191-219.

- ↑ Watson, Alexander: “Unheard-of Brutality”. Russian Atrocities against Civilians in East Prussia, 1914-15, in: The Journal of Modern History 86/4 (2014), pp. 780-825, issued by the University of Chicago Press, online: http://research.gold.ac.uk/11072/1/HIS_Watson2014.pdf (retrieved: 11 May 2016).

- ↑ Prusin, A.V.: Nationalizing a Borderland. War, Ethnicity, and Anti-Jewish Violence in East Galicia, 1914-1920, Tuscaloosa 2005, p. 29.

- ↑ Calculated from reports by Regierungspräsidenten Allenstein and Gumbinnen, 16 February and 21 April 1915. Geheimes Staatsarchiv, Berlin, XX. HA Rep. 2II, 3560: fo. 158 and I. HA Rep. 90A, 1064: report pages 7-8; and Landräte reports for Johannisburg (15 February 1915), Lötzen (18 February 1915), Sensburg (19 February 1915) and Lyck (26 February 1915) districts. Archiwum Państwowe w Olsztynie: RP Allenstein: 177: fo. 21-23, 27-28, 31-35 and 45-47.

- ↑ Gause, Die Russen in Ostpreußen 1931, pp. 113-120.

- ↑ Regierungspräsident Gumbinnen, 21 April 1915. Geheimes Staatsarchiv, Berlin, I. HA Rep. 90A, 1064: report pages 7-8.

- ↑ See especially Lohr, Eric: Nationalizing the Russian Empire. The Campaign against Enemy Aliens during World War I, Cambridge et al. 2003, pp. 121-165.

- ↑ Gause, Die Russen in Ostpreußen 1931, pp. 236-282. Also, Tiepolato, Serena, “…und nun waren wir auch Verbannte. Warum? Weshalb?” Deportate prussiane in Russia 1914-1918, in: DEP – Deportate, esuli, profughe. Rivista telematica di studi sulla memoria femminile 1 (2004), pp. 59-85.

- ↑ Reichsarchiv, Der Weltkrieg 1925, p. 329 and Gause, Die Russen in Ostpreußen 1931, pp. 69-70.

- ↑ Watson, “Unheard-of Brutality” 2014.

- ↑ For propaganda, see Jahn, Peter: Zarendreck, Barbarendreck – Die russische Besetzung Ostpreußens 1914 in der deutschen Öffentlichkeit, in: Eimermacher, Karl and Volpert, Astrid (eds.): Verführungen der Gewalt. Russen und Deutsche im Ersten und Zweiten Weltkrieg, Munich 2005; and Watson, Ring of Steel 2014; for Hindenburg, see Golz, Anna von der: Hindenburg. Power, Myth, and the Rise of the Nazis, Oxford and New York 2009 and Pyta, Wolfram: Hindenburg. Herrschaft zwischen Hohenzollern und Hitler, Munich 2007.

- ↑ Golz, Hindenburg 2009.

- ↑ Traba, Robert: Ostpreußen – die Konstruktion einer deutschen Provinz. Eine Studie zur regionalen und nationalen Identität 1914-1933, Osnabrück 2010, pp. 50-53.

- ↑ See the historiographical overview in Kolb, Eberhard and Schumann, Dirk: Die Weimarer Republik, Munich 2013, pp. 238-246.

- ↑ Krumeich, Gerd: Versailles 1919. Der Krieg in den Köpfen, in: Krumeich, Gerd (ed.): Versailles 1919. Ziele – Wirkung – Wahrnehmung, Essen 2001, pp. 53-64.

- ↑ For the Ruhr occupation, see: Krumeich, Gerd and Schröder, Joachim (ed.): Der Schatten des Weltkriegs. Die Ruhrbesetzung 1923, Essen 2004; Fischer, Conan: The Ruhr crisis, 1923-1924, Oxford et al. 2003. On the French occupation policy in Germany after World War One in general see Poidevin, Raymond and Bariéty, Jacques: Frankreich und Deutschland. Die Geschichte ihrer Beziehungen 1815–1975, Munich 1982; Lauter, Anna-Monika: Sicherheit und Reparationen. Die französische Öffentlichkeit, der Rhein und die Ruhr (1919-1923), Essen 2006; Pawley, Margaret: The watch on the Rhine. The military occupation of the Rhineland, 1918-1930, London et al. 2007; Jeannesson, Stanislas: French policy in the Rhineland, 1919-1924, in: Fischer, Conan and Sharp, Alan (ed.): After the Versailles Treaty. Enforcement, compliance, contested identities, London et al. 2008, pp. 57-68. On German foreign policy see Krüger, Peter: Versailles. Deutsche Außenpolitik zwischen Revisionismus und Friedenssicherung, Munich 1986.

- ↑ See Lauter, Sicherheit und Reparationen 2006, pp. 48-57.

- ↑ Jardin, Pierre: La politique rhénane de Paul Tirard (1920-1923), in: Revue d’Allemagne et des pays de langue allemande 2 (1989), pp. 208-216; Lauter, Sicherheit und Reparationen 2006, pp. 58-65.

- ↑ See Koller, Christian: ”Von Wilden aller Rassen niedergemetzelt“. Die Diskussion um die Verwendung von Kolonialtruppen in Europa zwischen Rassismus, Kolonial- und Militärpolitik 1914–1930, Stuttgart 2001; Wigger, Iris: Die ”Schwarze Schmach am Rhein“. Rassistische Diskriminierung zwischen Geschlecht, Klasse, Nation und Rasse, Münster 2006.

- ↑ See Winkler, Heinrich August: Weimar, 1918-1933. Die Geschichte der ersten deutschen Demokratie, Munich 2005, pp. 146-158; Krüger, Peter: Versailles. Deutsche Außenpolitik zwischen Revisionismus und Friedenssicherung, Munich 1986, pp. 116-132.

- ↑ Jeannesson, Stanislas: Poincaré, la France et la Ruhr 1922–1924. Histoire d'une occupation, Strasbourg 1998, pp. 137-143, 151-157.

- ↑ Kleinschmidt, Christian: Rekonstruktion, Rationalisierung, Internationalisierung. Aktive Unternehmensstrategien in Zeiten des passiven Widerstands, in: Krumeich and Schröder (eds.), Der Schatten des Weltkriegs 2004, pp. 133-147.

- ↑ See Krüger, Gerd: “Wir wachen und strafen!” – Gewalt im Ruhrkampf 1923, in: Krumeich and Schröder (eds.): Der Schatten des Weltkriegs 2004, pp. 233-255.

- ↑ Krumeich, Gerd: Der “Ruhrkampf” als Krieg. Überlegungen zu einem verdrängten deutsch-französischen Konflikt, in: Krumeich and Schröder (eds.), Der Schatten des Weltkriegs 2004, p. 16.

- ↑ Jeannesson, Stanislas: Übergriffe der französischen Besatzungsmacht und deutsche Beschwerden, in: Krumeich and Schröder (eds.), Der Schatten des Weltkriegs 2004, p. 214. They were not comparable to the high number of victims of the immediate post-war fighting in the Ruhr in 1919-1920, let alone to the number of victims of the German occupation of Belgium and northern France during the First World War. Still, they reveal a remarkable level of violence.

- ↑ Krumeich, Der ”Ruhrkampf“ als Krieg, in: Krumeich and Schröder (eds.), Der Schatten des Weltkriegs 2004, pp. 14-24; Jeannesson, Poincaré, la France et la Ruhr 1998, pp. 205-208; see numerous examples of propaganda posters and pamphlets in Krumeich and Schröder (eds.), Der Schatten des Weltkriegs 2004, pp. 323-356.

Selected Bibliography

- Becker, Jean-Jacques / Krumeich, Gerd: Der Große Krieg. Deutschland und Frankreich im Ersten Weltkrieg 1914-1918, Essen 2010: Klartext.

- Bell, Johannes (ed.): Völkerrecht im Weltkrieg. Dritte Reihe im Werk des Untersuchungsausschusses, volume 1, Berlin 1927: Deutsche Verlagsgesellschaft für Politik und Geschichte.

- Der Weltkrieg 1914-1918. Die militärischen Operationen zu Lande. Die Befreiung Ostpreußens, volume 2, Berlin 1925: Mittler, 1925.

- Fischer, Conan: The Ruhr crisis, 1923-1924, Oxford; New York 2003: Oxford University Press.

- Gause, Fritz: Die Russen in Ostpreussen 1914/15. Im Auftrage des Landeshauptmanns der Provinz Ostpreussen, Königsberg 1931: Gräfe und Unzer.

- Jahn, Peter: 'Zarendreck, Barbarendreck'. Die russische Besetzung Ostpreußens 1914 in der deutschen Öffentlichkeit, in: Eimermacher, Karl (ed.): Verführungen der Gewalt. Russen und Deutsche im Ersten und Zweiten Weltkrieg, Paderborn 2005: Fink, pp. 223-242.

- Jeannesson, Stanislas: Poincaré, la France et la Ruhr, 1922-1924. Histoire d'une occupation, Strasbourg 1998: Presses universitaires de Strasbourg.

- Kolb, Eberhard / Schumann, Dirk: Die Weimarer Republik, Munich 2013: Oldenbourg.

- Koller, Christian: 'Von Wilden aller Rassen niedergemetzelt.' Die Diskussion um die Verwendung von Kolonialtruppen in Europa zwischen Rassismus, Kolonial- und Militärpolitik (1914-1930), Stuttgart 2001: Steiner.

- Krumeich, Gerd: Versailles 1919. Der Krieg in den Köpfen, in: Krumeich, Gerd / Fehlemann, Silke (eds.): Versailles 1919. Ziele, Wirkung, Wahrnehmung, Essen 2001: Klartext Verlag, pp. 53-64.

- Krumeich, Gerd / Schröder, Joachim (eds.): Der Schatten des Weltkriegs. Die Ruhrbesetzung 1923, Essen 2004: Klartext.

- Lauter, Anna-Monika: Sicherheit und Reparationen. Die französische Öffentlichkeit, der Rhein und die Ruhr (1919-1923), Essen 2006: Klartext.

- Pawley, Margaret: The watch on the Rhine. The military occupation of the Rhineland, 1918-1930, London 2007: I. B. Tauris.

- Salm, Jan: Ostpreussische Städte im Ersten Weltkrieg. Wiederaufbau und Neuerfindung, Munich 2012: Oldenbourg.

- Tiepolato, Serena: '…und nun waren wir auch Verbannte. Warum? Weshalb?' Deportate prussiane in Russia 1914-1918, in: DEP – Deportate, esuli, profughe. Rivista telematica di studi sulla memoria femminile 1, 2004, pp. 59-85.

- Traba, Robert: Ostpreussen - die Konstruktion einer deutschen Provinz. Eine Studie zur regionalen und nationalen Identität 1914-1933, Osnabrück 2010: Fibre.

- Watson, Alexander: Ring of steel. Germany and Austria-Hungary at war, 1914-1918, London 2014: Allen Lane.

- Watson, Alexander: 'Unheard-of brutality.' Russian atrocities against civilians in East Prussia, 1914-15, in: The Journal of Modern History 86/4, 2014, pp. 780-825.

- Wein, Franziska: Deutschlands Strom - Frankreichs Grenze. Geschichte und Propaganda am Rhein 1919-1930, Essen 1992: Klartext.

- Wigger, Iris: Die 'Schwarze Schmach am Rhein.' Rassistische Diskriminierung zwischen Geschlecht, Klasse, Nation und Rasse, Münster 2007: Westfälisches Dampfboot.