A New Technique for Saving Lives↑

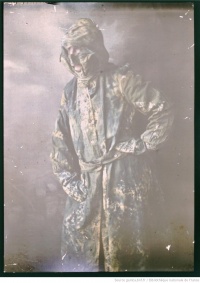

Camouflage was invented by two French painters mobilised in the 6th Artillery Regiment: Lucien Victor Guirand de Scévola (1871-1950) and Louis Guingot (1864-1948). As early as August 1914, they hid their guns under branches and canvases painted in hues matching their natural surroundings so as to avoid detection by the enemy. They had artillery-men wear earth-coloured coats that allowed them to blend into the landscape. The new coats thus concealed their blue tunics and trousers (a rather less conspicuous uniform that the one of the infantry, blue and red, whose sad consequences in the early stages of the conflict are well known).

Following the experiments and demonstrations carried out by a small group of artists, the minister of war was convinced of the technique’s effectiveness and officially established a Camouflage Section on 14 August 1915. Scévola was appointed commander in chief and Jean-Louis Forain (1852-1931) inspector general. The section was allowed to use workshops in order to make the equipment requested from all across the Western Front. Painters and sculptors representing all artistic genres participated in the workshops. However, set painters and stage decorators, who were well-practiced in trompe l’oeil painting, and cubist artists, who had mastered the art of breaking down objects’ true shapes, were particularly well represented among the artists.

The Workshops and Their “Art”↑

In Paris, the workshop on the Buttes-Chaumont, directed by Abel Truchet (1857-1918), trained over 200 artists. The other workshops were divided between the various army groups: Amiens (transferred to Chantilly in 1917), Châlons-sur-Marne, Nancy and Epernay. Secondary workshops were set up in Bergues, Noyon, Bar-le-Duc, Belfort, Soissons, Epinal, etc. They required a large number of personnel, including carpenters, sheet-metal workers, mechanics and plasterers.

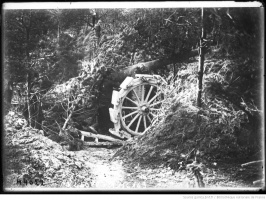

Organised in small specialised teams, camouflage artists reconnoitred the terrain or works to be concealed and supervised the installation of the camouflaged objects or machines. Fittings and raffia netting were installed on artillery pieces and batteries. Observatories were set up in sentry boxes called “molehills,” built into the parapets of trenches, in armoured replica trees (installed overnight in place of real ones), or in fake extensions of genuine ruins. Periscopes were inserted into wooden posts or shrubs. Canvases and hedges concealed roads, buildings, locks, railway tracks and sometimes entire villages. Camouflage artists also painted trompe l’oeil and set up fake positions, dummies and various lures. They also did not hesitate to move real landmarks in order to misdirect the enemy.

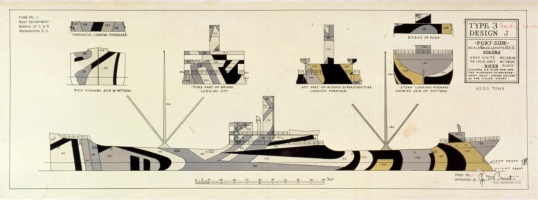

Painting irregular patterns onto artillery pieces, railroad equipment, trucks, gunboats and other machines disrupted their true lines and deceived the enemy as to their actual nature. According to this principle, camouflage was also applied to the air force and the navy. Both observation and combat planes were painted in hues that made them less conspicuous to the eye of an observer. Ships’ hulls were painted in large, motley strips of gradated shades and oblique lines, creating an optical effect that tricked the enemy into misidentifying the ship.

The British, Belgian, Italian, American and German armies also established workshops and formed teams of camouflage artists working on their own fronts.

Physicists, engineers, chemists and architects brought valuable help to the development and the effectiveness of deception techniques, thanks to their knowledge of the structure of materials, optical effects and light incidence. However, it was artists who – thanks to their imagination, their sense of the subtleties of colour, tone and matter, and their ability to draw on the spot or from memory – made the greatest contribution to camouflage’s success.

Cécile Coutin, Bibliothèque nationale de France

Section Editor: Emmanuelle Cronier

Selected Bibliography

- Blechman, Hardy: Disruptive pattern material. An encyclopedia of camouflage, Richmond Hill 2004: Firefly Books.

- Coutin, Cécile: Tromper l'ennemi. L'invention du camouflage moderne en 1914-1918, Paris 2015: Éditions Pierre de Taillac.

- Hartcup, Guy: Camouflage. A history of concealment and deception in war, New York 1980: Scribner's.

- Montella, Fabio: L'arma che inganna. Il mascheramento, in: Garuti, Alfonso / Taraborelli, Elia (eds.): Carpi fronte interno, 1915-1918, Modena 2014: Mc Offset, pp. 355-372.

- Newark, Timothy: Camouflage, London; New York 2007: Thames & Hudson.

- Nübel, Christoph: Modern warfare. Camouflage tactics (‘Tarnung’) in the German army during the First World War, in: First World War Studies 6/2, 2015, pp. 113-132, doi:10.1080/19475020.2015.1067636.