A Problematic Peace Settlement↑

Following victory in November 1918, France sought long-term control of the Rhineland, but Germany anticipated a moderate peace between equals. Both countries were to be disappointed. Britain and the United States insisted on a temporary occupation of the Rhineland, fearing that tough peace terms would fuel German revisionism. However, the reparations settlement imposed on Germany was harsh and met with a toxic mixture of anger and despair.

French Strategy and Objectives↑

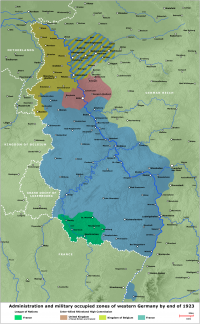

The Versailles Treaty empowered the Allies to impose sanctions should Germany default on the peace terms; from an early stage France envisaged exploiting these powers to sustain its presence in the Rhineland. In March 1921, when stalemate threatened the final terms of the reparations settlement, French and Belgian troops, with British blessing, occupied Düsseldorf and the western Ruhr cities of Duisburg and Ruhrort to bring the Germans to heel. The Ruhr, just east of the Allied-occupied zone, was targeted due to its pre-eminence as Germany’s coal mining, metallurgical, heavy engineering, and armaments production centre.

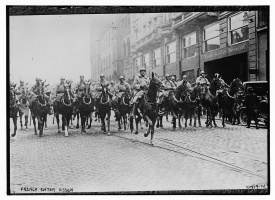

During 1922, Germany was wracked by a deepening economic and social crisis, prompting its government to suspend the cash payment of reparations in August. France believed this reflected a deeper pattern of German bad faith, but her main ally, Britain, proved unsupportive. Gripped by a sense of abandonment, France secured Belgian and nominal Italian support to invoke Versailles’ sanctions clauses. The French Premier, Raymond Poincaré (1860-1934), announced that France would occupy the Ruhr District to extract reparations. However, this obscured the enormity of his ambitions, that “by March or April Germany will fall to pieces”[1] and that they “were no longer discussing payments, France had to develop a political plan.”[2] Belgium was determined to secure its share of reparations, but its participation in the operation also reflected a desire to contain French ambitions as the occupation began on 11 January 1923.

France pursued its agenda remorselessly. German officials and their families were hounded from the region, displaced by new institutions that answered to Paris. The administration and taxation of the mining and metallurgical industries was transferred to the Inter-allied Control Mission for Factories and Mines (MICUM) and military law was imposed. The border between the Ruhr and Germany was sealed and eventually a new French-backed currency was proposed for the Rhine and Ruhr. There was also French and Belgian support during October 1923 for an abortive separatist rising in the Rhineland.

German Passive Resistance↑

The German government under Wilhelm Cuno (1876-1933) struggled to resolve the Ruhr crisis. Passive resistance against the Franco-Belgian occupation was overwhelmingly non-violent. It originated within the Ruhr’s organised, republican labour movement, before extending to public officials and the business community, although a few right-wing paramilitary adventurers waged a more violent campaign that provoked ferocious French and Belgian reprisals.

Even peaceful defiance exacted a very heavy price as the Allies imposed a blockade that decimated the Ruhr’s economy and disrupted food supplies. 300,000 starving children were evacuated to family farms in unoccupied Germany, while in the Ruhr itself resisters and occupiers engaged in a grinding battle of attrition. Women paid a heavy price as orderly life disintegrated and they encountered random harassment by the occupying military.

Plunging tax receipts and the cost of underwriting inoperative factories and mines destroyed Germany’s public finances and currency. Political and social unrest bubbled up across the country, with food riots sweeping the Ruhr, alongside intimations of collaboration with the occupiers. Gustav Stresemann (1878-1929) became Chancellor in August 1923 and called off passive resistance on 26 September.

Mutual Failure and the Genesis of Franco-German Rapprochement↑

Stresemann’s government managed to stabilise its worthless currency, but at the cost of brutal deflation and mass unemployment. France, it briefly appeared, had triumphed, but it derived little material benefit from the Ruhr occupation and, as its own finances deteriorated, it turned to its allies for help. This came at a price, for Britain and America opposed French hegemony in Europe as much as they did German. The Americans proposed international mediation of the reparations question, to which France reluctantly agreed. The resulting Dawes Report recommended the resumption of reparations payments, but on condition France evacuated the Ruhr and desisted from interference in the German economy.

The Ruhr crisis fostered a transition from mutual confrontation to collaboration, as the Locarno Accords (October 1925) initiated an era of rapprochement personified by the French and German Foreign Ministers Aristide Briand (1862-1932) and Gustav Stresemann.

Conan Fischer, University of St. Andrews

Section Editor: Emmanuel Debruyne

Notes

- ↑ Jeannesson, Stanislas: Poincaré, la France et la Ruhr (1922-1924). Histoire d’une occupation, Strasbourg 1998, p. 116.

- ↑ Soutou, Georges-Henri: Vom Rhein zur Ruhr: Absichten und Planungen der französischen Regierung, in: Krumeich, Gerd and Schröder, Joachim (eds.): Der Schatten des Weltkriegs. Die Ruhrbesetzung 1923, Essen 2004, p. 66.

Selected Bibliography

- Depoortere, Rolande: La question des réparations allemandes dans la politique étrangère de la Belgique après la Première Guerre mondiale, 1919-1925, Brussels 1997: Académie royale de Belgique.

- Fischer, Conan: The Ruhr crisis, 1923-1924, Oxford; New York 2003: Oxford University Press.

- Jeannesson, Stanislas: Poincaré, la France et la Ruhr, 1922-1924. Histoire d'une occupation, Strasbourg 1998: Presses universitaires de Strasbourg.

- Krumeich, Gerd / Schröder, Joachim (eds.): Der Schatten des Weltkriegs. Die Ruhrbesetzung 1923, Essen 2004: Klartext.

- O'Riordan, Elspeth Y.: Britain and the Ruhr crisis, Basingstoke 2001: Palgrave.