Introduction↑

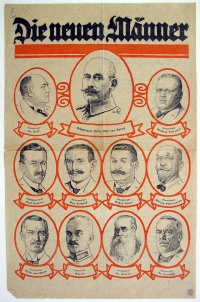

The political system under the 1871 constitution of Imperial Germany can be described on one hand as a federation of formerly sovereign principalities and free city states, with the king of Prussia presiding over the federation and assuming the hereditary title as German emperor (Kaiser). On the other hand, it was a constitutional monarchy with strict separation of powers. The executive branch of government had a triangular shape, headed by the Kaiser. The civilian part of the executive was led by the imperial chancellor. The chancellor was not elected but instead appointed by the Kaiser and responsible only to him. The military part of the executive was led by the high command of the army’s General Staff and by the Imperial Admiralty; the chancellor had no authority over their strategic planning and decisions. Coordination between the civilian and military branch of government fell under the Kaiser's responsibility.

| Emperor | Chancellor | Chief of the General Staff of the Field Army (Supreme Army Command, OHL) |

|

Wilhelm II (15 June 1888 – 9 November 1918) |

Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg (7 July 1909 – 13 July 1917) |

Helmut von Moltke (1 August – 14 September 1914 [officially 25 October 1914]) |

| Georg Michaelis (14 July – 30 October 1917) | Erich von Falkenhayn (14 September 1914 [officially 25 October 1914] – 19 August 1916) | |

| Georg von Hertling (1 November 1917 – 4 October 1918) | Paul von Hindenburg (19 August 1916 – 3 July 1919) | |

| Prince Maximilian von Baden (5 October – 9 November 1918) |

Table 1: Imperial Executive, 1914-1918

The legislative branch of government consisted of two chambers, the Bundesrat, representing the states, and the Reichstag, representing the people. Without the consent of a majority in both chambers no law, including the budget, could be passed. The 397 members of the Reichstag were democratically elected – beginning in 1888 for a five-year term – by universal male suffrage. Although the Reichstag’s majority was indispensable in passing legislation, it neither elected the chancellor nor could it depose him by a vote of no confidence; it was a purely legislative body.

The results of the last Reichstag election before the war, in 1912, had made the government’s task of building a majority for its legislative agenda more difficult than ever. The majority comprised of the conservatives, representing aristocratic and agricultural interests, and the Centre Party, representing the Catholic minority, on which Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg (1856-1921) had relied before the elections did not exist anymore. Instead, the Marxist party of the industrial working class, the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), comprised the strongest faction in the Reichstag. Although the SPD was deeply divided over the question of how to achieve socialism, either by revolutionary mass strikes or a reformist strategy, it was considered common sense among the party’s parliamentary group not to vote for the budget, particularly not the military budget. For the Army Expansion Bill of 1913, which was crucial in preparing Germany for a possible war, Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg managed to win the support of both the liberals and conservatives, who were strictly opposed on domestic issues such as constitutional reform, and of the Centre Party to secure the bill’s adoption.

| Party | |

|

| Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) | |

|

| Centre Party | |

|

| Conservatives (German Conservative Party & German Reich Party) | |

|

| National Liberal Party | |

|

| Progressive People’s Party (left liberals, FVP) | |

|

| Other (ethnic and regional parties, non-aligned) | |

|

Table 2: Composition of the 1912 Reichstag[1]

Domestic Truce (Burgfrieden) and War Aims Majority↑

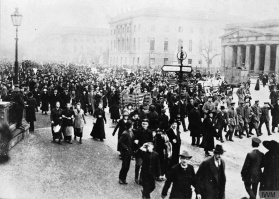

As a legislative body, the Reichstag had no say in the decision to declare war first on Russia and then on France. In fact, it was not even in session when the war began. Wilhelm II, German Emperor's (1859-1941) famous appeal for national unity in his opening speech of the Reichstag session on 4 August 1914, in which he declared that he no longer saw parties, only Germans (“Ich kenne keine Parteien mehr, ich kenne nur noch Deutsche!”),[2] did not become a reality until the SPD spokesman, Hugo Haase (1863-1919), declared that the SPD would support the war effort and vote for the war credits bill. Ironically, Haase had argued against this decision in the previous internal SPD debates.[3] Why did the SPD, which had up until the end of July 1914 organised well-attended peace demonstrations, decide to vote for the war credits? The party mainstream, the reformist wing and the trade unions had accepted Bethmann Hollweg’s arguments that Germany had been attacked by Tsarist autocratic Russia when Russia began mobilisation and that Germany was leading a defensive war. The fact that Russian troops were starting to invade East Prussia as the Reichstag was in session enhanced the chancellor’s credibility. Furthermore, apprehension that the SPD would be banned under the regulations of the state of emergency which had come into effect with the declaration of war played an important role in the party and union leadership’s decision-making. Another reason was that socialist parties in the Entente states also supported their countries’ war efforts. And last but not least, particularly reformists in the SPD were optimistic that once the SPD’s patriotism could no longer be called into doubt the government would no longer refuse their demands for constitutional reform, most prominently for the end of the Prussian three-class suffrage.[4]

As a symbol of national unity, a truce of all domestic political competition was proclaimed. Until the end of the war, no general election would be held and unavoidable by-elections would be non-competitive. Consequently, the composition of the 1912 Reichstag did not change during the war.

The consensus of August 1914 was soon challenged at both ends of the political spectrum. As in most nations at war, the war boosted nationalist feelings in Germany. Not realising how difficult the Reich’s strategic position really was once the Schlieffen Plan had failed, bourgeois and conservative parties, industrial and agricultural interest groups, nationalist organisations such as the Pan-German League, academic elites and many others began to beleaguer the government with demands that the war could only end with a victorious peace. Their demands included more or less extensive annexations of French, Belgian and Russian territories. Thus, the conditions under which Social Democrats and left liberals had supported the war were not accepted by large segments of the political class. A peace treaty as the result of negotiations instead of complete victory was not acceptable to the new majority in the Reichstag, which included conservatives, National Liberals, the Centre Party and even parts of the left liberal group. Behind the facade of Burgfrieden a new nationalistic majority had isolated the SPD once again.

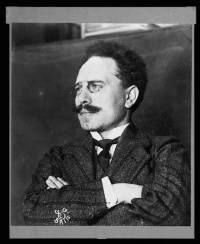

This, in turn, served to confirm the suspicions of a minority of the SPD Reichstag members that Bethmann Hollweg’s claim that Germany was only defending itself against Entente aggression had never been more than government propaganda. In December 1914, Karl Liebknecht (1871-1919) became the first SPD member of the Reichstag who did not feel compelled to submit to party discipline and voted against the second war credits bill. One year later, in December 1915, there were already twenty dissenters in the SPD parliamentary group, and in March 1916 the anti-war dissenters were excluded from the SPD group and formed the Socialist Working Group (Sozialistische Arbeitsgemeinschaft) in the Reichstag.[5] After another year of bitter quarrels within the SPD, the Independent Socialist Party (Unabhängige Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, or USPD) was founded in April 1917 and the split of the SPD was complete. Since the issue over which the party split occurred was support for the war and not the previous struggle over party strategy, the USPD was almost as heterogeneous as the SPD had been before the war. The revisionist and pacifist Eduard Bernstein (1850-1932), for instance, found himself, again, in the same party as the former SPD “chief ideologue” Karl Kautsky (1854-1938) and with revolutionaries such as Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg (1871-1919), all of whom had been his foes in the SPD’s internal debates before the war. Already in 1914 the latter two had founded Die Internationale group, renamed Spartacus League in 1916, which joined the USPD in 1917 and formed the core of the Communist Party founded at the beginning of 1919. The Spartacus League, which was of course banned under the state of emergency, worked neither for a peace through victory nor through negotiations but instead tried to agitate the masses in order to bring about a revolutionary peace made by the working class in all nations at war. The revolutionary strategy won support within the party after the Bolshevik revolution in Russia and the January 1918 strikes in Germany.

Any breach of national unity – so was the general conviction (not only in Germany) – would be perceived as a sign of weakness by the enemy and would encourage their will to fight on. As a result, Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg had to pander to both the annexationist majority in the Reichstag as well as to the SPD in order to keep up appearances of Burgfrieden. This is one of the reasons why it is so difficult for historians to determine what his own intentions really were.[6]

Changing Power Relations in the German Government↑

Under the imperial constitution, the chancellor held little authority over the military and its strategic decisions. Once the war began, the balance within the government tipped more and more in favour of military leadership. The civilian government’s job was increasingly to provide what the military needed in order to win the war: arms and ammunition, men, money, food and, more generally, the support of the home front. This entailed a great expansion of administration and regulation.[7]

An important aspect was that the British naval blockade had cut off Germany from most of its pre-war overseas trade. In consequence, an administrative system of controlling prices, requisitioning and rationing provisions was introduced and could not prevent – and in some instances its ineptness even increased – food shortages. The fact that those parts of the population who could not afford to buy on the black market had to suffer from starvation, particularly in the winters of 1916, 1917, and 1918, was widely attributed to the British blockade. In the face of popular dissatisfaction the government felt an increasing need to pander to the Reichstag as the representative of the people. The latter’s “power of the purse” also made it a crucial political actor with regard to financing the war. However, all this did not mean that the Reichstag, or even its majority, had a consistent strategy to expand and exert its influence. The struggles within the different branches of government over the issue of submarine warfare can illustrate this.

In order to prevent German overseas trade, the British navy did not blockade German ports but closed the entire North Sea to German shipping. This was done by blockading the Channel and the strait between Scotland and Norway. The German battle fleet that had been created by the secretary of the navy, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz (1849-1930), was unable to do anything against this kind of blockade and remained in port for most of the war. In this aggravating situation Tirpitz devised a solution that had hardly been thought of before the war. He suggested declaring a counter-blockade against Britain by threatening to sink all ships, regardless of whether they were British, Entente, or neutral, by submarines. By February 1915 this new strategy was adopted and announced to all neutral powers. As had been anticipated by Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg, the United States, as the most important neutral power, immediately protested against the possible destruction of American ships and lives.[8] In May 1915 the Americans’ fear became reality: a German submarine sank the Lusitania and 120 Americans drowned. The American ultimatum that Germany should either revert to forms of naval warfare in accordance with international law or face the consequences resulted in a bitter conflict within Germany on how to react to the American demand. The navy, particularly Tirpitz, wanted to refuse flatly while Bethmann Hollweg feared that American entry into the war would definitely tip the scale in favour of the Entente. He was therefore ready to abandon unrestricted submarine warfare. As the Reichstag, particularly the Main Committee (Hauptausschuss), which was formed in 1915 and remained in session throughout the war, had gained political clout, both sides tried to win its support. Tirpitz was more successful; the war aims majority strongly opposed any concession to US interests, only the SPD sided with Bethmann Hollweg. In August 1915, when another American ship, the Arabic, was sunk, it was not the Reichstag but military leadership whose voice proved decisive. Erich von Falkenhayn (1861-1922) convinced the emperor that American entry into the war could be crucial and the Kaiser ordered an end to unrestricted submarine warfare.[9]

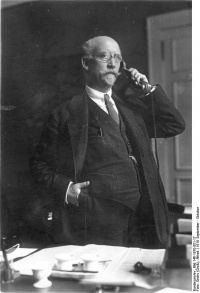

Yet as the strategy of attrition on the Western Front yielded no progress, for many Germans submarine warfare remained the wonder weapon to defeat Britain. Early in 1916, Falkenhayn changed his mind and demanded the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare. Under these circumstances Bethmann Hollweg looked for support in the Reichstag. He could count on the SPD and the FVP, which shared his view that the chances of drawing the United States into the war were high if submarine warfare was indeed resumed. Whether he could win a majority for his position depended on the Centre Party, which had so far gone along with the war aims majority. However, on this particular issue a politician of a younger generation, Matthias Erzberger (1875-1921), proved influential. He had been associated with Tirpitz in the past and was expected to support him. However, Erzberger was not convinced by the navy’s argument that Britain could be defeated in six weeks – or in six months, as other admirals had contended. Thus, in February 1916 he was able to convince the Centre Reichstag faction not to support the conservatives and National Liberals, and thereby Tirpitz.[10]

When Bethmann Hollweg was able to convince the Kaiser at the beginning of March 1916 not to revoke the decision on submarine warfare, Tirpitz handed in his resignation, which was accepted immediately. This came as a shock to the nationalist public. The right-wing factions in parliament reacted quickly and tried to turn Bethmann Hollweg’s victory over Tirpitz into a defeat. But again, a resolution drafted by the conservatives and National Liberals, which amounted to a declaration of no confidence against the chancellor, was not supported by the Centre. The constellation was almost a prefiguration of the 1917 majority consisting of the Centre, FVP and SPD.

The nationalist right was not ready to accept defeat. The chancellor was attacked as weak and even defeatist by a plethora of pamphlets during the summer of 1916. Under the strain of this propaganda, Bethmann Hollweg hoped to profit from the enormous popularity of Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934), which is one of the reasons why he agreed when Hindenburg replaced Falkenhayn as chief of the Supreme Army Command (Oberste Heeresleitung, or OHL). Another reason was that Hindenburg had also counselled that the risks of unrestricted submarine warfare with regard to the neutral powers outweighed possible benefits. However, relying on Hindenburg’s support to convince the Kaiser of his policy not to provoke the United States into war proved to hold risks for the stability of his parliamentary support. Within a few weeks the traditional leaders of the Centre Party, who had resented Erzberger’s growing influence, succeeded in getting a compromise resolution at the party’s congress passed, which practically left the decision whether unrestricted submarine warfare should be resumed to Hindenburg alone. This not only weakened the chancellor’s position, it also undermined the Reichstag’s influence on strategy and foreign policy. In October 1916, when conservatives and National Liberals happily supported a Reichstag resolution that echoed the Centre’s and passed the decision to the OHL, the war aims majority was intact once again. When within three months, after the fall of Romania, Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937) reversed their position and demanded the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare, neither the chancellor nor the Kaiser put up any resistance and accepted their demand. This is indicative of the changed power relations within the imperial government, of the strong position of the Third OHL, and of the way the Reichstag had forfeited all influence on strategic decision-making.[11]

The Reversal of the Reichstag Majority↑

The winter of 1916/17 was the hardest so far for the German working class, large segments of which were severely undernourished. In order to keep up morale, the SPD pushed the issue of the Prussian three-class suffrage. The imperial chancellor, who also held the office of Prussian prime minister, realized that soldiers returning from the front could not be denied equal voting rights. But he was not strong enough to overcome the resistance of Prussian conservatives against constitutional reform; all he could do was to convince the Kaiser – as the king of Prussia – to promise constitutional reforms after the war in his Easter message of 1917.[12] This was enough to alienate the Conservative Party – and the Third OHL – even more than before but not enough to fulfil the hopes for reform. The SPD, FVP, and even parts of the Centre Party and the National Liberals began to doubt Bethmann Hollweg’s ability to lead the way towards constitutional reforms.

When at the beginning of July 1917 the Reichstag Main Committee had to debate a new bill for financing the war, Erzberger again took the initiative.[13] In his speech he relentlessly made clear that all the navy’s assurances that Britain would ask for peace within six months because of unrestricted warfare had been proven wrong.[14] As a result, he suggested a Reichstag resolution stating that the German people were prepared to end unrestricted submarine warfare and to accept a negotiated peace without annexations or reparations. The text of the resolution was drafted in a newly created committee in which those parliamentary factions who supported Erzberger’s suggestion, i.e. the SPD, the left liberal FVP and the Centre Party, were represented and decided to formalize their cooperation (“Interfraktioneller Ausschuss", or IFA). It was the ambition of this new majority to establish de facto if not de jure a form of parliamentary government in which the government would have to accept the majority’s political program.[15] It goes without saying that both, the resolution and the attempts to factually change the constitution, were fiercely opposed by the nationalist right, which responded by organizing a new radical nationalist party, the Fatherland Party.[16] They sought to rally popular protest against the Peace Resolution in order to demonstrate that the Reichstag majority did not represent the majority of the people. However, the pacifist left, the USPD, also opposed the Peace Resolution by questioning its sincerity and its chances of success.[17]

When the resolution was passed in the Reichstag a new chancellor, Georg Michaelis (1857-1936), was already in office. The OHL, particularly Ludendorff, had worked hard to persuade the Kaiser to dismiss Bethmann Hollweg. The latter had lost most of his support among the Reichstag factions because he had failed to bring about constitutional reform and because he was tainted with the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare.[18] Although the Reichstag politicians had played a role in ousting Bethmann Hollweg, they had no influence on the selection of his successor, who was the OHL’s candidate. Although Michaelis lasted only a little more than three months in office he managed to inflict lasting damage. His assurances to cooperate closely with the new Reichstag majority turned out to be no more than lip service when he qualified his support for the Peace Resolution by adding “as I understand it” (“wie ich sie auffasse”)[19], which meant, in fact, that he never intended to conform his policies to the resolution. The obfuscating German reply to the papal mediation effort of September 1917,[20] which made no mention of any renunciation of annexations comparable to the Peace Resolution, clearly showed that.

From October 1917 to October 1918: The Chancellorship of Count Hertling↑

When Michaelis had alienated the Reichstag majority to such an extent that his position had become untenable he was replaced by Count Georg von Hertling (1843-1919). The latter, a Bavarian Catholic and Centre Party politician, had been a member of the Reichstag for many years before being appointed Bavarian prime minister in 1912. In spite of his political past, he was deeply sceptical about the imperial government’s parliamentary responsibility. Yet he accepted that he was expected to lead the government in accordance with the new Reichstag majority.[21] However, he was too old and too weak to enforce any policies against the preferences of Hindenburg and Ludendorff. Neither the peace settlement with Bolshevik Russia nor the imperial government’s response to President Woodrow Wilson’s (1856-1924) Fourteen Points speech was in line with the Reichstag’s Peace Resolution. And when the OHL decided to risk a decisive offensive on the Western Front instead of calling for a peace of understanding from a strong defensive position after having been victorious on the Eastern Front, neither Hertling nor the IFA were able to do anything against it. In fact, when the military situation seemed to have turned in favour of Germany, the Reichstag majority did not actually disintegrate, but it did not pursue its Peace Resolution very consistently either.[22] The Centre Party, where Erzberger had lost much of his influence with the ascent of Hertling, and even the FVP supported the annexationist Brest-Litovsk peace treaty. At that point, the former war aims majority seemed more of a reality than the new Peace Resolution majority. That a few politicians from the IFA parties were granted positions in government was more a fig leaf than a true step in the direction of a parliamentary government.

The political situation only began to change when the military situation took a turn for the worse and when Hindenburg and Ludendorff’s decisive battle was lost.

Revolution from Above: Military Defeat and Parliamentary Government↑

In mid-August 1918, German troops began retreating on the Western Front and in the second half of September 1918, Germany’s Turkish, Bulgarian, and Austrian allies acknowledged defeat and asked the Allied powers for a ceasefire. On 29 September 1918, Hindenburg and Ludendorff finally disclosed to the Kaiser that the military situation was desperate and that the war could not be won. In the face of this admission of defeat they demanded two things: The civilian government was to ask US President Wilson for the terms of an armistice on the basis of his Fourteen Points and, at the same time, the imperial constitution should be reformed to include the political parties in government responsibility. In the face of defeat the OHL, which had dominated German politics for such a long time, shied away from the responsibility for ending the war and burdened others with it. Chancellor Hertling did not accept the demands for democratic reform and handed in his resignation. On 3 October 1918, his successor, Prince Maximilian von Baden (1867-1929), was appointed and formed a cabinet in which several party leaders became state secretaries, including, for the first time in German history, two from the SPD: Philipp Scheidemann (1865-1939) and Gustav Bauer (1870-1944).

The constitutional reforms that were prepared by the new government and adopted by the Reichstag on 26 October 1918 (which was coincidentally the same day on which Ludendorff was dismissed from the OHL) consisted of four different aspects. First, membership in the Reichstag and a government office were made compatible. Second, a vote of no confidence against the chancellor in the Reichstag would result in his dismissal, meaning that full parliamentary control was established. Third, the separation of civilian and military government was abolished so that the chancellor would be fully responsible to the Reichstag for all executive decisions. Finally, a declaration of war as well as a peace treaty would need the consent of the Reichstag. These four provisions were intended to establish Germany as parliamentary monarchy. What was even more important at the time, their purpose was to meet President Wilson’s conditions for a ceasefire.

However, the reforms came too late to save the German monarchy. The admiralty’s decision to seek a final sea battle rather than surrender the fleet to the Allied powers, which was one of the conditions for an armistice, was taken without the government’s or the Reichtag’s knowledge. This sparked mutiny and revolution.[23] Within two weeks, revolutionary Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils spread all over Germany; on 9 November 1918 the movement had reached Berlin, where Chancellor von Baden declared the Kaiser's abdication without the consent of the monarch, who all but fled into Dutch exile. The prince handed over the chancellorship to the SPD leader Friedrich Ebert (1871-1925), whose fellow in party leadership, Philipp Scheidemann, proclaimed the German Republic[24], preceding Karl Liebknecht’s proclamation of the Socialist Republic by only a few hours.

Conclusion↑

Even a statesman like Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898) had to fight hard during the war of 1870/71 in order to successfully assert civilian authority over that of the military in political decision-making. In World War I the cabinets of Bethmann Hollweg, Michaelis, and Hertling were not as successful as Bismarck had been, particularly after Hindenburg and Ludendorff were appointed to the OHL. The longer the war lasted, the more military authorities dominated politics in Germany – in contrast to Entente powers such as Britain or France, let alone the United States. The Kaiser proved unable to provide a balance between civilian and military leadership.

The legislative body, the Reichstag, gained political stature during the war. The political truce between the parties was a powerful symbol of a people united in the war effort that the government worked hard to maintain. However, underneath the truce, political differences lingered. The nationalist right demanded an annexationist peace of victory and opposed constitutional reform. Moderate liberals and social democrats advocated constitutional reforms and stood for a negotiated peace of international reconciliation. The Centre Party, true to its name, stood closer to the nationalist side during the first years of the war and helped to forge the war aims majority. When the situation both on the military and on the home front deteriorated in 1917, the Centre Party came under the influence of its left wing, changed its position, and helped to create a new majority which drafted the Peace Resolution of July 1917. But even this new majority was unable to use parliament’s power of the purse as a lever to force through parliamentary responsibility of government against the resistance of conservatives and the OHL. Only when Hindenburg and Ludendorff decided to disburden themselves of their political dominance and their responsibility in the face of military defeat in September 1918, reforms leading toward parliamentary government were introduced in a rush.

Even if the majority parties had not been able to force a parliamentary system on the other institutions, their cooperation was not futile. Friedrich Ebert, even when he led the revolutionary Council of the People’s Deputies, insisted on democratic instead of revolutionary legitimization and on the election of a National Constitutional Assembly at the earliest possible moment (January 1919). That was, among other things, the result of the social democratic experience of close and trusting cooperation with FVP and Centre Party politicians in the IFA. This cooperation had successfully prepared the ground for the further cooperation of the “Weimar Coalition”, consisting of SPD, Centre Party and left liberals, in drafting the constitution for the Weimar Republic in 1919.

Torsten Oppelland, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena

Section Editor: Christoph Cornelißen

Notes

- ↑ Ritter, Gerhard A.: Wahlgeschichtliches Arbeitsbuch. Materialien zur Statistik des Kaiserreichs 1871-1918, Munich 1980, p. 42.

- ↑ For the digital version of his speech, see http://www.reichstagsprotokolle.de/Blatt_k13_bsb00003402_00013.html (retrieved 3 May2016).

- ↑ Cf. Miller, Susanne/Matthias, Erich (eds.): Das Kriegstagebuch des Reichstagsabgeordneten Eduard David 1914-1918, Düsseldorf 1966, pp. 3f.

- ↑ Regarding the SPD’s incentives to vote for that very bill, see Miller, Susanne: Burgfrieden und Klassenkampf. Die deutsche Sozialdemokratie im Ersten Weltkrieg, Düsseldorf 1974, pp. 68-74 as well as Rauh, Manfred: Die Parlamentarisierung des Deutschen Reiches, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 293-297.

- ↑ Cf. Kruse, Wolfgang: Krieg und Nationale Integration. Eine Neuinterpretation des sozialdemokratischen Burgfriedensschlusses 1914/15, Essen 1993, pp. 178-184, 214-219; for a more general yet detailed elaboration of the German Social Democrats during the First World War, see Miller, Burgfrieden 1974.

- ↑ Cf. Jarausch, Konrad: The Enigmatic Chancellor. Bethmann Hollweg and the Hubris of Imperial Germany, New Haven 1973; Ritter, Gerhard: Staatskunst und Kriegshandwerk. Das Problem des Militarismus in Deutschland, Vol. III: Die Tragödie der Staatskunst. Bethmann Hollweg als Kriegskanzler (1914-1917), Munich 1964.

- ↑ For an elaboration of the development of the administrative bodies as well as the growing antagonism between the military and the civilian leadership, see Rauh, Parlamentarisierung 1977, pp. 300-362.

- ↑ For President Wilson’s reaction, see Angell, Norman (ed.): America and the European War. 1915, London 2013 (reprinted), pp. 140-142.

- ↑ Cf. Oppelland, Torsten: Reichstag und Außenpolitik im Ersten Weltkrieg. Die deutschen Parteien und die Politik der USA 1914-1918, Düsseldorf 1995, pp. 60-77, 86f.

- ↑ Cf. ibid., pp. 94f., 105-115.

- ↑ Cf. ibid., pp. 132-147.

- ↑ For the whole speech, see Huber, Ernst Rudolf (ed.): Dokumente zur deutschen Verfassungsgeschichte, Stuttgart 1961, Vol. II, pp. 467-68.

- ↑ Regarding Erzberger’s motivations and the background of his speech in detail, see Oppelland, Reichstag 1995, pp. 235-243.

- ↑ Schiffers, Reinhard/Koch, Manfred (eds.): Der Hauptausschuss des Deutschen Reichstags 1915-1918, Vol. III: 1917, Düsseldorf 1981, pp. 1525-1529.

- ↑ An extensive description of the IFA’s plans and ambitions is given by Bermbach, Udo: Vorformen parlamentarischer Kabinettsbildung in Deutschland. Der Interfraktionelle Ausschuss 1917/18 und die Parlamentarisierung der Reichsregierung, Cologne/Opladen 1967, pp. 83-123.

- ↑ Cf. Hagenlücke, Heinz: Deutsche Vaterlandspartei. Die nationale Rechte am Ende des Kaiserreichs, Düsseldorf 1997, esp. pp. 143-163.

- ↑ The final version is printed in Matthias, Erich (ed.): Der Interfraktionelle Ausschuss 1917/18, Vol. II, Düsseldorf 1959, p. 114f.

- ↑ Cf. Oppelland, Reichstag 1995, pp. 251-253; Epstein, Klaus: Matthias Erzberger and the Dilemma of German Democracy, Princeton 1959, p. 207.

- ↑ http://www.reichstagsprotokolle.de/Blatt_k13_bsb00003406_00481.html (retrieved 3 May 2016).

- ↑ Steglich, Wolfgang (ed.): Der Friedensappell Papst Benedikts XV. vom 1. August 1917 und die Mittelmächte. Diplomatische Aktenstücke des Deutschen Auswärtigen Amtes, des Bayerischen Staatsministeriums des Äussern, des Österreichisch-Ungarischen Ministeriums des Äussern und des Britischen Auswärtigen Amtes aus den Jahren 1915-1922, Wiesbaden 1970, pp. 160-162.

- ↑ Cf. Epstein, Erzberger 1959, pp. 247f., 251f.

- ↑ Cf. Ibid., pp. 260f.

- ↑ Cf. Sauer, Wolfgang: Das Scheitern der parlamentarischen Monarchie, in: Kolb, Eberhard (ed.), Vom Kaiserreich zur Weimarer Republik, Cologne 1972, pp. 77-99.

- ↑ For his proclamation, see Scheidemann, Philipp: Memoiren eines Sozialdemokraten, Vol. 2, Dresden 1928, pp. 311f.

Selected Bibliography

- Angell, Norman: America and the European war, Boston 1915: World Peace Foundation.

- Bermbach, Udo: Vorformen parlamentarischer Kabinettsbildung in Deutschland. Der Interfraktionelle Ausschuss 1917/18 und die Parlamentarisierung der Reichsregierung, Cologne; Opladen 1967: Westdeutscher Verlag.

- Epstein, Klaus: Matthias Erzberger and the dilemma of German democracy, Princeton 1959: Princeton University Press.

- Hagenlücke, Heinz: Deutsche Vaterlandspartei. Die nationale Rechte am Ende des Kaiserreiches, Düsseldorf 1997: Droste.

- Huber, Ernst Rudolf: Dokumente zur deutschen Verfassungsgeschichte. Deutsche Verfassungsdokumente 1851-1918, volume 2, Stuttgart 1961: Kohlhammer.

- Jarausch, Konrad Hugo: The enigmatic chancellor. Bethmann Hollweg and the hubris of imperial Germany, New Haven 1973: Yale University Press.

- Kruse, Wolfgang: Krieg und nationale Integration. Eine Neuinterpretation des sozialdemokratischen Burgfriedensschlusses 1914/15, Essen 1993: Kartext Verlag.

- Kühne, Thomas: Demokratisierung und Parlamentarisierung. Neue Forschungen zur politischen Entwicklungsfähigkeit Deutschlands vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Geschichte und Gesellschaft 31/2, 2005, pp. 293-316.

- Loth, Wilfried: Katholiken im Kaiserreich. Der politische Katholizismus in der Krise des wilhelminischen Deutschlands, Düsseldorf 1984: Droste.

- Machtan, Lothar: Die Abdankung. Wie Deutschlands gekrönte Häupter aus der Geschichte fielen, Berlin 2008: Propyläen.

- Matthias, Erich: Der interfraktionelle Ausschuß 1917/18, volume 2, Düsseldorf 1959: Droste-Verlag.

- Matthias, Erich: Der interfraktionelle Ausschuß 1917/18, volume 1, Düsseldorf 1959: Droste-Verlag.

- Miller, Susanne: Burgfrieden und Klassenkampf. Die deutsche Sozialdemokratie im Ersten Weltkrieg, Düsseldorf 1974: Droste.

- Miller, Susanne (ed.): Das Kriegstagebuch des Reichstagsabgeordneten Eduard David, 1914-1918, Düsseldorf 1966: Droste.

- Oppelland, Torsten: Reichstag und Aussenpolitik im Ersten Weltkrieg. Die deutschen Parteien und die Politik der USA 1914-1918, Düsseldorf 1995: Droste.

- Rauh, Manfred: Die Parlamentarisierung des Deutschen Reiches, Düsseldorf 1977: Droste.

- Retallack, James N.: The German right, 1860-1920. Political limits of the authoritarian imagination, Toronto 2006: University of Toronto Press.

- Ritter, Gerhard: Staatskunst und Kriegshandwerk. Die Tragödie der Staatskunst. Bethmann Hollweg als Kriegskanzler, volume 3, Munich 1964: Oldenbourg.

- Ritter, Gerhard: Staatskunst und Kriegshandwerk. Die Herrschaft des deutschen Militarismus und die Katastrophe von 1918, volume 4, Munich 1968: Oldenbourg.

- Sauer, Wolfgang: Das Scheitern der parlamentarischen Monarchie, in: Kolb, Eberhard (ed.): Vom Kaiserreich zur Weimarer Republik, Cologne 1972: Kiepenheuer & Witsch, pp. 77-99.

- Scheidemann, Philipp: Memoiren eines Sozialdemokraten, Dresden 1928: C. Reissner.

- Schiffers, Reinhard (ed.): Der Hauptausschuss des Deutschen Reichstags 1915-1918, Düsseldorf 1981-1983: Droste.

- Steglich, Wolfgang (ed.): Der Friedensappell Papst Benedikts XV. vom 1. August 1917 und die Mittelmächte, Wiesbaden 1970: Steiner.