The Campaign↑

During the early 1920s, an average of 25,000 colonial French soldiers participated in the occupation of German territory west of the river Rhine. The vast majority of these troops came from Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia, with significantly smaller contingents hailing from Indochina, Madagascar, and Senegal. Stationing colonial troops in the Rhineland enabled French authorities to demobilize European French soldiers more quickly to aid the reconstruction effort at home. A certain element of “psychological warfare” may also have played a role in the decision to deploy colonial troops; after all, Germany lost all of its own colonies in 1919. German pro-colonial revisionists clearly viewed the presence of African occupation soldiers as a provocation, contrasting the alleged depravity of France’s colonial subjects with the myth of the loyal Askari who they claimed had remained disciplined and true to their German masters to the end.[1] The movement against the African French soldiers used the racist epithet “schwarze Schmach am Rhein” (“black horror on the Rhine”). It emerged in the aftermath of the failed right-wing Kapp-Lüttwitz coup of March 1920 and reached its zenith during 1920-1921.

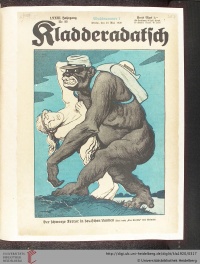

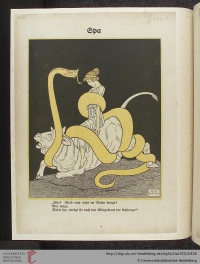

Schwarze Schmach propaganda centered on highly graphic depictions of alleged sexual crimes committed by African soldiers against Rhenish women and children. The rape of “innocent German maidens” by African “barbarians” functioned as a metaphor for Germany’s “brutal subjection” under the Versailles Treaty and was aimed to deflect attention away from the debate over German war crimes. Within the Reich, a broad political spectrum ranging from the Majority Social Democrats to the nationalist Right supported the protests against the schwarze Schmach; only the parties of the radical left (Independent Socialists and Communists) refused to participate. The Reich government played a major role in orchestrating the propaganda campaign. At national and regional levels, officials collaborated closely with a multiplicity of private individuals and associations. Thus, for instance, the semi-official Rhenish Women’s League (Rheinische Frauenliga, or RFL) coordinated the schwarze Schmach protests of a broad range of women’s organizations and often relied on feminists’ international networks to distribute propaganda abroad. Internationally, “black horror” propaganda initially enjoyed significant popular appeal, especially in Austria, England, Sweden, and the United States. The British labor politician, Edmund Dene Morel (1873-1924), became a vocal supporter of the schwarze Schmach campaign. At the turn of the 20th century, Morel had been a leader of the movement against Leopold II, King of the Belgians' (1835-1909) brutal regime in the Congo Free State, which claimed the lives of millions of Africans. In his influential pamphlet, The Horror on the Rhine (1920), Morel attacked the French government for tearing the African soldiers from their families and homelands and using them as “cannon fodder” in its imperialist wars. African men’s “primitive” sex drive, he argued, though necessary to guarantee species survival in the harsh African environment, inevitably resulted in mass rapes of white women once these troops were “thrust upon” the Rhineland. Morel’s disturbing combination of humanitarian concerns and racist stereotypes, as well as his close collaboration with the German government and German nationalists in the production of “black horror” propaganda, are illustrative of the ways in which the First World War complicated conflicts over colonialism in Europe. In the early 1920s, Allied critics of imperialism often sided with German opponents of France’s African troops, even though the latter included many German pro-colonial revisionists. Pro-colonialists in the Entente countries, on the other hand, frequently found themselves confronted with the task of defending African soldiers against accusations of rape and “barbarism” that had long been staples of racist justifications of the “white man’s burden.”[2] The perplexing political realignments evident over the course of the “black horror” campaign underline the war’s unsettling implications for the stability of inherited colonial hierarchies and modes of racialist discourse.

Tensions and Decline↑

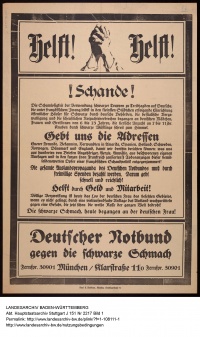

At least as striking as the “black horror” campaign’s initial success is its rather swift demise after 1921. Increasingly, schwarze Schmach propaganda evoked domestic and international criticism. This prompted German officials to intervene against some of the most radically racist strands within the movement, and ultimately to scale down government involvement in the campaign. For instance, Bavarian and Reich officials were instrumental in forcing the right-wing extremist president of the Munich-based German Emergency League against the Black Horror (Deutscher Notbund gegen die schwarze Schmach, or DNB), Heinrich Distler (1885-?), to step down and terminate his membership. In August 1921, after repeated protests by the French ambassador, the appeal board of the Berlin censorship board (Filmoberprüfstelle) banned the propaganda film Die schwarze Schmach (1921), directed by Carl Boese (1887-1958), for which Distler had written the screenplay. Schwarze Schmach propaganda increasingly strained relations between the population of the occupied Rhineland and the Reich government. It was a sensitive issue, especially in light of significant popular support for Rhenish autonomy during the immediate post-war years. According to more extreme forms of “black horror” propaganda, sexual crimes, racial “miscegenation,” and general lawlessness were rampant in the occupied territories. The resultant decline in tourism was a major blow to the Rhenish economy. The apocalyptic scenario of the allegedly imminent complete “Mulattoization” (Mulattisierung) of the Rhineland cherished by DNB propagandists formed part of a broader right-wing misogynist discourse about the “white shame” (weiße Schmach), which accused especially working-class Rhenish women of sleeping with national and racial “enemies.” This questioning of proletarian women’s patriotic loyalties points to the pronounced class bias frequently visible in “black horror” propaganda. The fact that Rhenish women’s leaders resented accusations of “immorality” and “patriotic unreliability” leveled at them by right-wing extremists was an important factor in the decision of the leaders of the Rhenish Women’s League to deemphasize “black horror” themes in the League’s activities. For German men, "black horror" propaganda's emphasis on white male impotence in the face of Africans' allegedly ferocious sexual appetite and violence ultimately exacerbated the sense of emasculation in the aftermath of military defeat.[3] Even before the Franco-Belgian occupation of the Ruhr industrial district in January 1923 led to the reorientation of official German propaganda efforts, the mass appeal of the movement against the schwarze Schmach had diminished significantly.

Legacies and Significance↑

One of the most problematic legacies of the schwarze Schmach campaign was the social stigmatization of the children of Rhenish mothers and African French soldiers. In the Weimar Republic, those calling for the forced sterilization and exile of these children remained unsuccessful. In contrast, no legal or moral obstacles prevented the compulsory sterilization of hundreds of Afro-German descendants of French colonial soldiers under the Nazi regime. During the invasion of France in 1940, the German Wehrmacht massacred thousands of African French soldiers. The racial hatred fomented by the schwarze Schmach campaign contributed fatefully to making these war crimes possible.

The history of the schwarze Schmach highlights the lasting impacts of World War I atrocity propaganda on post-war discourses on gender, race, and nation. Important elements of “black horror” propaganda were modeled on Allied depictions of the barbaric, ape-like German “Hun” raping innocent Belgian women and children. Simultaneously, the schwarze Schmach campaign built on wartime German propaganda against colonial Allied soldiers. The initial success of the schwarze Schmach campaign underlines the pervasive nature of racial and gender anxieties in the post-war world. It illustrates the war-induced shift toward new types of popularized foreign-policy discourses centered on the theme of the sexual victimization of women and children.[4]

Julia Roos, Indiana University, Bloomington

Section Editor: Michelle Moyd

Notes

- ↑ Maß, Sandra: Weiße Helden, schwarze Krieger. Zur Geschichte kolonialer Männlichkeit in Deutschland 1918-1964, Cologne 2006, pp. 56-70.

- ↑ Christian Koller has argued that the need to counter “black horror” propaganda led to noticeable shifts in official French depictions of African soldiers. See Koller, Christian: “Von Wilden aller Rassen niedergemetzelt”. Die Diskussion um die Verwendung von Kolonialtruppen in Europa zwischen Rassismus, Kolonial- und Militärpolitik (1914-1930), Stuttgart 2001, p. 339.

- ↑ See Maß, Weiße Helden 2006.

- ↑ Especially Gullace, Nicoletta: Sexual violence and family honor. British propaganda and international law during the First World War,” in: American Historical Review 102/3 (1997), pp. 714-747.

Selected Bibliography

- Koller, Christian: 'Von Wilden aller Rassen niedergemetzelt.' Die Diskussion um die Verwendung von Kolonialtruppen in Europa zwischen Rassismus, Kolonial- und Militärpolitik (1914-1930), Stuttgart 2001: Steiner.

- Le Naour, Jean-Yves: La honte noire. L'Allemagne et les troupes coloniales françaises 1914-1945, Paris 2003: Hachette Littératures.

- Mass, Sandra: Weisse Helden, schwarze Krieger. Zur Geschichte kolonialer Männlichkeit in Deutschland 1918-1964, Cologne 2006: Böhlau.

- Roos, Julia: 'Huns' and other 'Barbarians'. A movie ban and the dilemmas of 1920s German propaganda against French colonial troops, in: Historical Reflections 40/1, 2014, pp. 67-91.

- Wigger, Iris: Die 'Schwarze Schmach am Rhein.' Rassistische Diskriminierung zwischen Geschlecht, Klasse, Nation und Rasse, Münster 2007: Westfälisches Dampfboot.