Early Career↑

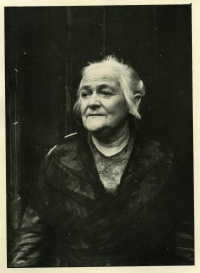

Clara Josephine Zetkin (1857-1933), neé Eißner, was born in Saxony, the eldest daughter of a modest bourgeois family. Her parents adhered as much to Lutheran religiosity as to a liberal-humanist worldview and provided their children with the best possible education. They moved to Leipzig in 1872 where Clara trained and began working as a private teacher. Having joined the Socialist Workers’ Party (SAP) in 1878, she left Germany as a consequence of Bismarck’s anti-socialist legislation and moved to Paris in 1882. There she met and fell in love with the Russian revolutionary Ossip Zetkin (1850-1889) and gave birth to her sons Maxim Zetkin (1883-1965) and Kostja Zetkin (1885-1980), caring for them during the day and working as a writer and translator at night. In 1890, they moved back to Germany, where she found work in the social democratic press.

As a close companion of Rosa Luxemburg (1871-1919), Karl Liebknecht (1871-1919), and Franz Mehring (1846-1919), Zetkin was a staunch proponent of revolutionary Marxism, internationalism, and anti-imperialism. She believed that the emancipation of women would follow naturally from the liberation of the international proletariat in a socialist revolution. In her view, gender inequality was a consequence of economic exploitation. As editor-in-chief of the SPD-affiliated Die Gleichheit (1891-1917), she advocated her feminist-internationalist version of Marxism. Her commitment was shaped by a protestant work ethic, a quasi-religious belief in the righteousness of her worldview, and a longing for discipline and leadership – qualities she found realized in Vladimir Il’ich Lenin (1870-1924) from 1917 onwards, whom she hailed as the messiah of socialism.

Wartime Activities and Imprisonment↑

The outbreak of the war in 1914 radically disillusioned Zetkin. She became sick and depressed and grew hostile towards what she considered a failing “proletariat”. Estranged from the SPD, she convened a women’s international conference in Bern in 1915, holding up the ideal of internationalism amidst the bloodshed facilitated by the nationalist “opportunism” of the Second International. She was arrested in 1915 for her anti-war stance and indicted for “treason”; due to her poor health she was released from prison after four months. She participated in the founding of the Spartakusbund, joining the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (Unabhängige Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, USPD) in 1917 and the Communist Party of Germany (Die Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, KPD) in 1918. With Lenin’s seizure of power during the Russian Revolution she became a fervent supporter of the Bolsheviks and unequivocally justified their brutal regime as necessary “self-defense against the forces of counterrevolution.”[1] In the nascent Soviet state, Karl Marx’s (1818-1883) philosophy was being realized by “hammer and sword.”

Post-war Career and Death↑

As member of the German parliament between 1920 and 1933 she represented the KPD’s radical left and became a leading Comintern advocate and president of the Rote Hilfe. In 1932, as senior Reichstag president, Zetkin called for the (re)unification of the German proletariat and pointed to the Soviet Union as the “world historical proof” of capitalism’s doom. At the same time, she lamented the failure of the delusional “masses” to recognize National Socialism’s true intentions. Shortly before Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) came to power she had travelled to Russia where she died in June 1933.

Christina Morina, University of Amsterdam

Section Editor: Christoph Nübel

Notes

- ↑ Zetkin, Clara: Ein Jahr proletarischer Revolution in Russland (November 1918). Frauen-Beilage der ”Leipziger Volkszeitung” vom 13. November 1918, in: Zetkin, Clara: Ausgewählte Reden und Schriften, Berlin 1957, pp. 43-54

Selected Bibliography

- Badia, Gilbert: Clara Zetkin. Eine neue Biographie, Berlin 1994: Dietz.

- Evans, Richard J.: Theory and practice in German social democracy 1880-1914: Clara Zetkin and the socialist theory of women's emancipation, in: History of Political Thought 3/2, 1982, pp. 285-304.

- Hervé, Florence: Clara Zetkin. Oder, dort kämpfen, wo das Leben ist, Berlin 2011: Dietz.

- Klaßen, Angela: Mädchen- und Frauenbildung im Kaiserreich 1817-1918: emanzipatorische Konzepte bei Helene Lange und Clara Zetkin, Würzburg 2003: Ergon-Verl..

- Puschnerat, Tania: Clara Zetkin: Bürgerlichkeit und Marxismus, Essen 2003: Klartext.

- Zetkin, Clara: Ausgewählte Reden und Schriften, 3 volumes, Berlin 1957-1960: Dietz.