Career↑

Otto Weddigen (1882-1915) grew up in a bourgeois family in Herford in eastern-Westphalia. He joined the navy in 1901, serving in the German East-Asia squadron before he was transferred to the submarine division in 1908. He was made commander of U-9 in 1911.

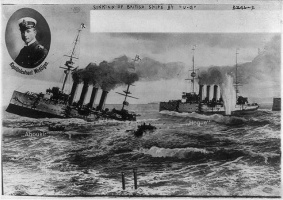

The "heroic" captain of U9↑

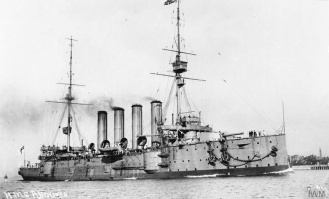

On 22 September 1914, in the North Sea, Weddigen’s submarine sunk the British armoured cruisers, Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy, in the space of just over an hour. At first the Aboukir’s captain mistakenly thought that his ship had struck a mine and called upon the Hogue and Cressy to approach to rescue his men. As they did so, U-9 fired another torpedo which struck Hogue. While the Cressy tried to save the crew from the other two sinking ships, it was struck by a further torpedo and sunk. In total 1,467 British officers and men lost their lives, while 837 were saved by Royal Navy ships and fishing vessels. On 14 October 1914, U-9 sunk the British cruiser Hawke with the loss of 500 lives.

In late September 1914 Weddigen was awarded the iron cross first class. He was also the first naval officer during the war to receive the Pour le mérite – Imperial Germany’s highest military honour. His historical significance is threefold. Weddigen’s successes helped to diminish German naval enthusiasts’ disappointment that the opening months of the war had passed by without a major naval victory. They also contributed to the remobilization of German society just as many Germans came to realize that the invasion of France would not lead to instant victory in the west. Most importantly, the example of U-9 provided an impetus to call for the naval leadership to deploy submarines as an offensive weapon, helping to shape the decision making process that led to the German campaigns of unrestricted submarine warfare.

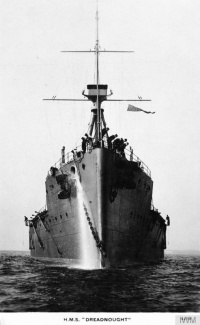

Sinking by Dreadnought↑

In response to the British blockade, in February 1914, the Imperial German Navy began its first campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare. As commander of U-29 Weddigen was in the southern-Irish sea where his mission was to attack trade shipping. Acting independent of his commands, he sailed north to the main British military harbour at Scapa Flow. Hoping to launch a surprise attack on British warships, his submarine was spotted and rammed by the British warship Dreadnought. Soon after it sank. There were no survivors.

Place in the war’s culture and memory↑

Already a popular figure who represented wartime heroism, in death Weddigen’s symbolic value increased. His image was used to call on Germans to continue to make sacrifices in support of the war. It was central to the representation of the war at sea in Germany, and as such it was part of the wider cultures of war that developed in all belligerent countries. Later Weddigen’s image and memory was also used in support of the National Socialist dictatorship.

Mark Jones, Freie Univeristät Berlin and University College Dublin

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Selected Bibliography

- Halpern, Paul G.: A naval history of World War I, Annapolis 1994: Naval Institute Press.

- Jones, Mark: Graf von Spee’s Untergang and the corporate identity of the Imperial German Navy, in: Redford, Duncan (ed.): Maritime history and identity. The sea and culture in the modern world, International library of war studies, London 2013: I. B. Tauris, pp. 183-202.

- Schilling, René: 'Kriegshelden'. Deutungsmuster heroischer Männlichkeit in Deutschland 1813-1945, Paderborn 2002: Schöningh.

- Wolz, Nicolas: Das lange Warten. Kriegserfahrungen deutscher und britischer Seeoffiziere, 1914 bis 1918, Paderborn 2008: Schöningh.