Introduction↑

The South African participation in the First World War has been overshadowed by the Union Defence Force (UDF) deployment to France and Flanders during 1916-1918. South African national memory of the war primarily focuses on the defence of Delville Wood and the sinking of the S.S. Mendi. The precursor to these events was the South African invasion of German South West Africa (GSWA) in September 1914. The UDF, established in 1912, was poorly prepared for deployment in the event of war. The Union of South Africa was marred by political uncertainties and tensions during 1914, mainly over its active participation in the war against Germany. Whilst South Africa was a metaphorical tinderbox waiting to catch a spark, its leaders hoped that participation in the war could serve as a means to unite the Afrikaans and English-speaking sections of the country behind a common goal. The South African decision to invade GSWA in September 1914 failed to do so. Seen as the precursor to the Afrikaner Rebellion that erupted within the Union of South Africa, the full-scale invasion of GSWA was temporarily put on hold. The UDF operations during the Afrikaner Rebellion were used to gain the required operational experience and efficiency needed for war. This article examines the South African invasion of GSWA by focusing on the history and geography of the colony up to 1914, the opposing war aims and military organisations of the South African and German forces, and the two separate UDF invasions of the colony.

History and Geography of South West Africa (to 1914)↑

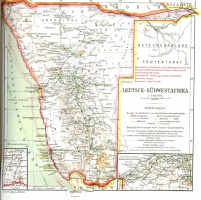

On 24 April 1884, Germany formally proclaimed protection over Franz Adolf Eduard Lüderitz’s (1834-1886) economic endeavour at the Bay of Angra Pequena (Lüderitzbucht). By the end of August 1884, a German Protectorate was proclaimed in South West Africa, whereafter the entire coast was annexed.[1] A series of political and military treaties were signed with the local inhabitants of South West Africa by 1885, with Windhoek becoming the capital of the colony by 1890. Between 1893 and 1907 German control gradually extended into the hinterland, with German authorities undertaking military operations against the Oorlams, Namas, Bondelswarts, and Herero to ensure their complete subjugation.[2] The Herero Rebellion of 1904-1907 represented the most serious threat to German sovereignty in the colony. Lothar Von Trotha (1848-1920) met the rebellion with extreme violence, in what has been called the first genocide of the 20th century. By 1907 the German pacification of South West Africa was complete. Until 1914 the colony enjoyed a relatively stable period marked by economic prosperity and infrastructure developments.[3]

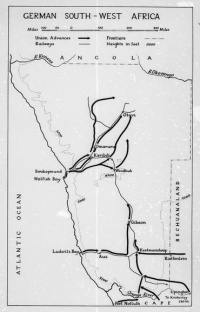

The political boundaries of GSWA were fixed upon a number of discernible geographical features, which aided in its defence. The southern boundary was the Orange River, the Atlantic coastline the western boundary, and the eastern boundary was the Kalahari Desert. Waterless areas, devoid of infrastructure, marked the terrain adjoining these borders. A military advance across these areas would be extremely difficult.[4] A railway line that stretched from Tsumeb in the north to Kalkfontein in the south connected the German political centres at Windhoek and Keetmanshoop. Two further parallel railway lines connected Lüderitzbucht with Seeheim and Swakopmund with Karibib. The railways formed the lifeline of the colony. The climate of the colony was considered healthy, although limited rainfall and access to water prevented any large scale concentration of forces. The geography and climate of the region remained paramount in the defence of GSWA.[5]

The Opposing War Aims, Armed Forces and Military Organisation↑

Germany South West Africa↑

In January 1914, the German Foreign Office instructed all colonies to revert to defensive measures in the event of war. The outbreak of war isolated the colonies from Germany since the Royal Navy would keep German shipping at bay. The civilian governors of the colonies, including Theodor Seitz (1863-1949) of GSWA, favoured colonial neutrality in the event of war, but would defend German sovereignty if needed. In GSWA the military commander, Colonel Joachim von Heydebreck (1861-1914), made optimal use of his central position within the colony to protect its borders against invasion. The railway network within the colony allowed Heydebreck to operate on interior lines of communication, offering him complete freedom of movement and action. He had planned to deploy his troops at four strategic locations throughout the colony; his forces were deployed at Windhoek and Keetmanshoop, and astride the railway lines connecting Lüderitz and Swakopmund with the hinterland.[6] Heydebreck intended to use his aircraft and mounted scouts to monitor the South African military’s movements along the colony’s border. In the event of an invasion, his troops would harass their lines of communication. Realising that access to water and good grazing would be paramount factors influencing any South African invasion; Heydebreck opted to use his troops to deny these resources to the invaders. He, however, would still have the freedom to use his internal lines of communication to retire and fall back on his supplies and strategic defences piecemeal.[7]

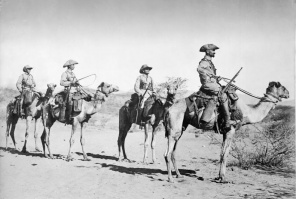

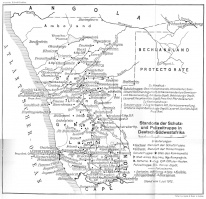

The Schutztruppen that Heydebreck had at his disposal for the defence of the colony were a well-trained force with ample experience in colonial warfare. The Schutztruppen answered directly to the Colonial Department of the German Foreign Office and numbered approximately 5,000 men. These included: 140 officers and 2,000 men of the Schutztruppen, 2,500 reservists, a camel corps, four field artillery batteries, a small air wing, 200 Afrikaner rebels, and 1,500 German policemen.[8] The Schutztruppen enjoyed a number of distinct advantages over their South African counterparts; better military organisation, a unified command structure, good training, and local knowledge. Reflecting the German perception of GSWA as a colony of European settlement, the local force was almost entirely composed of white troops. Given its recent history of conquest, GSWA could not rely on local black communities for support. The military leadership of Heydebreck was often questioned, and he remained unpopular amongst his troops who favoured his second-in-command, Major Viktor Franke (1865-1936).[9]

South Africa↑

On 7 August 1914 the British government requested that the Union of South Africa invade GSWA. Designated as an “urgent Imperial service”, the Committee on Imperial Defence (CID) required South Africa to capture the harbours of Lüderitzbucht and Swakopmund and the wireless stations at Windhoek, Swakopmund and Lüderitzbucht. The continued operation of the wireless stations during the war was a threat to British and Entente shipping, as they permitted Berlin to communicate with German warships on the high seas. On 10 August 1914 South Africa formally agreed to invade GSWA and meet all the CID objectives. Parliamentary support for the invasion was granted in September 1914 and South Africa officially declared war on 14 September 1914.[10] The South African pretext for going to war was essentially driven by the shrewd sub-imperialism of the South African Prime Minister, Louis Botha (1862-1919), and his close ally, Jan Smuts (1870-1950). Both men realised that the capture of GSWA could serve as the grounds for the eventual incorporation of the territory into the Union of South Africa. It thus remained imperative that South African troops be used to invade the German colony. The South African High Command realised that they had to act post-haste in terms of their planned military offensive, for Britain could easily despatch Indian or Australian troops to occupy GSWA if they tarried too long. In fact, Botha had grander visions for southern Africa; that of incorporating all the British High Commission territories into the Union of South Africa.[11]

The UDF mobilised approximately 100,000 men for active military service by 1914. Formed around the vestiges of the armed forces of the four former South African colonies, the UDF was a compromise between Boer and British military traditions. This had a direct impact on the nature, organisation, morale and military preparedness of the UDF before the outbreak of the war. By the latter half of 1914 the UDF was comprised of four distinct elements: a small permanent force, an active citizen force (ACF) of volunteer regiments, the defence rifle associations, and a cadet corps for boys. The organisational state of the UDF was a matter for grave concern. With no coherent central staff at Defence Headquarters and a severe lack of trained staff officers in general, the UDF was in a perilous state during September 1914.[12]

The Campaign↑

The First South African Invasion↑

The South African plan for the military invasion of GSWA was finalised on 21 August 1914. The plan for the invasion allowed for three separate columns to converge on GSWA. A column ("C" Force) under Colonel P.S. Beves (1863-1924) was to land at Lüderitzbucht, and through the help of the Royal Navy, destroy key infrastructure such as the wireless station. Further south, Brigadier General Henry Timson Lukin (1860-1925) and his column ("A" Force) would land at Port Nolloth and threaten the southern border of the colony. A final column ("B" Force) under Lieutenant-Colonel Salomon Gerhardus "Manie" Maritz (1876-1940) would invade GSWA from the east, with Upington as its base of operations.[13] The South African fighting contingent consisted of mainly white soldiers, with black auxiliaries acting in a supporting role. The plan for the invasion of GSWA suffered from a number of flaws. The three fighting columns would be deployed across a vast operational area stretching as an arch for 850 kilometers from Lüderitzbucht to Upington. Lateral communication between the forces would be impossible. The South African operations would be directed from Pretoria and careful timing and coordination were necessary to ensure that the three separate offensive operations gained local superiority over the German forces.[14]

Before parliamentary approval was granted for the South African invasion, the Union was thrown into turmoil. On 15 September 1914 Brigadier General Christian Frederick Beyers (1869-1914), the Commandant General of the ACF, along with several other officers and men, resigned from the UDF in protest of the South African decision to invade GSWA upon Imperial request. They claimed that they had no quarrel with their German neighbours who had actively supported them during the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902).[15] On 16 September 1914, the South African parliament approved the invasion of GSWA. On the operational front events now moved swiftly; Beves successfully occupied Lüderitzbucht on 18 September and accounted for his objectives immediately, whilst Lukin had his forces occupy the high ground and border posts at Raman’s Drift, Houms Drift, and Gudous. Lukin had planned to invade GSWA from across the Orange River then advanced on Seeheim via Raman’s Drift, Warmbad and Kalkfontein. The biggest obstacle to Lukin’s advance remained access to sufficient water for his force. A small force of South African troops occupied the waterholes at Sandfontein on 19 September 1914. Soon Pretoria pressured Lukin to occupy the position in force to hasten his advance on Warmbad. On 26 September 1914, the South Africans suffered a crushing defeat at Sandfontein at the hands of Heydebreck and his Schutztruppen. Heydebreck made good use of the terrain, his interior lines of communications and his superior forces at Sandfontein. Maritz caused great concern when he failed to send Lukin reinforcements and openly supported the Germans, by sharing military information with them on the dispositions of Lukin. On 9 October 1914 Maritz went into open rebellion with the majority of his force at Upington, and soon thereafter an immediate halt in offensive operations was called. Pretoria realised that it first needed to reorganise the UDF and deal with the Afrikaner Rebellion within its own borders, before it could complete the conquest of GSWA.[16]

The Second South African Invasion↑

By the latter half of December 1914 the Afrikaner Rebellion had been crushed, and Botha and Smuts could once more focus their attention on the conquest of GSWA. Smuts drew up a new plan for the invasion of the German colony; Swakopmund and Walvis Bay were to be used as staging areas for a direct advance on Windhoek. Botha had assumed the overall command of the South African invasion, thereby ensuring unity of command in the political and military spheres of the campaign.[17] Smuts believed that separate attacks along four different axes would deny the German forces the use of their interior lines of communication, and ensure the UDF operational success. Botha and Smuts aimed to destroy Heydebreck’s Schutztruppen in the field, thereby preventing a guerrilla campaign from ensuing. Four different forces converged on GSWA during early January 1915.[18] The Northern Force, under the personal command of Botha, operated from Walvis Bay and would threaten the German military and political seat at Windhoek. Botha’s Northern Force was the principal South African force in the field and was comprised of approximately 20,000 men by February 1915. The Eastern Force, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Christian Anthony Lawson Berrangé (1864-?), operated from Kuruman and was tasked with threatening the eastern border of GSWA with an advance across the Kalahari Desert. The Central Force, under the command of Brigadier General Sir Duncan McKenzie was tasked to advance from Lüderitzbucht via Aus towards the strategic railroad juncture at Seeheim and then onwards to Keetmanshoop. Under the command of Colonel Jacob L. van Deventer (1874-1922), the Southern Force would threaten the southern half of GSWA from their bases at Upington and Port Nolloth. The reorganisation within the UDF had a distinct impact on the leadership and command structures of the invading force. Botha appointed only trusted stalwarts to lead the offensive operations against the Germans, thereby abandoning the former policy of language equity and provincial representation within the UDF. Preference was given to more competent commanders who were willing to wage war with the Germans, including Coen Brits, Manie Botha, Jacob van Deventer, Johannes Alberts, and Christian Berrangé. Botha realised that the real fight would be against the harsh geography and climate of GSWA. An array of ancillary troops including engineers, medical and veterinary personnel, transport and logistical troops, armoured cars and some aeroplanes supported his forces.[19]

The second South African invasion of GSWA was a staccato affair, with operational advances predetermined by the availability of water and grazing. Nevertheless, Franke, who succeeded Heydebreck after his untimely death on 12 November 1914, completely underestimated South African operational mobility. Franke chose to fall back on Heydebreck’s strategy, responding piecemeal to South African operational movements, whilst the UDF was left to struggle with the inhospitable nature and geography of GSWA. The high speed of the South African manoeuvres and operational envelopments in the field ensured that Botha had made steady gains by the end of March 1915.[20] In the South and East, the combined efforts of Van Deventer and Berrangé’s forces ensured the capture of Kalkfontein by 5 April 1915. McKenzie’s forces occupied Aus by 30 March 1915, and only resumed their advance on Gibeon towards the end of April due to the ever-present problem of access to water. In the north, Botha captured Riet and Jakkalswater by 24 March 1915, but was forced to withdraw back to Swakopmund due to water scarcity. By 26 April 1915, Gibeon and Trekkopjes had been captured, forcing Franke to retreat further north. During the latter half of April 1915, Franke faced another serious internal military threat within GSWA. On 28 April 1915 the Rehoboth Basters, of mixed ethnicity and dubious loyalty, went into open rebellion due to the looming political and military power vacuum in central GSWA. The Rehoboth Basters offered Botha a token military force he could use in offensive operations against the Germans. Botha vehemently refused this offer on the premise that it was to be a "white man’s war". Franke and his forces were forced to deal with both an internal and external threat to German sovereignty, which resulted in the launching of a punitive raid against the Rehoboth Basters marked by excessive levels of violence and reprisals. By 8 May 1915 the expedition had to be called off due to the South African advance from the south. By 5 May 1915 the South Africans successfully captured Karibib, where after they occupied Windhoek unopposed on 15 May 1915.[21]

South Africa had met all of the CID’s objectives that had been set out in August 1914. By 21 May 1915, Seitz proposed an armistice to Botha based upon the territorial status quo. Botha and Smuts wanted to completely incorporate the territory into the Union of South Africa and outright ignored the proposal. By 18 June 1915 Botha resumed his advance against the German forces in the north of the colony through a series of forced marches and operational envelopments. On 1 July 1915 Botha’s forces successfully advanced on Otavifontein, which forced Seitz and Franke to reconsider their military and political options. By 9 July 1915 Botha accepted the surrender of GSWA at Otavifontein after a successful South African campaign marked by a high degree of operational mobility and manoeuvre. The high degree of operational mobility during the campaign ensured a relatively low casualty rate, with 529 South African and 1,188 German casualties respectively.[22]

The Aftermath↑

The South African occupation of South West Africa produced the first Allied armistice of the war, which was subsequently marked by effective cooperation between the former adversaries in the administration of the territory. The South African occupation heralded in some minor developments in both the economic and infrastructural spheres of the territory following the cessation of hostilities. Initially the South African authorities did not repatriate Germans from South West Africa on the basis of humanitarianism, but by 1918 approximately 6,000 German residents had been deported back to Germany. In turn, South Africa opted to re-settle the territory with poor rural Afrikaners, thereby strengthening their presence in the territory. Militarily, the UDF troops garrisoned there effectively supressed a number of internal threats to the Union’s sovereignty, which included the deposing of the Owambo Chief Mandume Ya Ndemufayo (1894-1917) in February 1917. By 1920 the League of Nations granted South Africa a class C mandate over GSWA, which effectively incorporated the territory into the Union on a political, economic, and military level.[23]

Conclusion↑

Military actions did not necessarily determine the outcome of the South African invasion of GSWA during 1914-1915; it was the ability of the UDF to overcome the unforgiving nature and geography of the colony that made the difference. A high degree of mobility and operational envelopments marked the UDF’s offensive operations, most importantly their constant need to secure access to water. The German defence of the colony was haphazard and lacked strategic direction. The successful South African conquest of GSWA was but the start of the Union’s contribution to the war effort. The UDF subsequently served in East Africa, the Middle East, France, and Flanders.

Evert Kleynhans, North-West University

Section Editor: Timothy J. Stapleton

Notes

- ↑ Pakenham, Thomas: The Scramble for Africa, London 2012, pp. 201-213.

- ↑ Bruwer, J.P. van S.: South West Africa: The Disputed Land, Johannesburg 1966, pp. 71-76.

- ↑ Van der Waag, Ian: The Battle of Sandfontein, 26 September 1914: South African military reform and the German South-West Africa campaign, 1914-1915, in: First World War Studies 4(2), 2013, pp. 143-145.

- ↑ Strachan, Hew: The First World War in Africa, Oxford; New York 2004, p. 65.

- ↑ General Staff: The Union of South Africa and the Great War: Official History; Pretoria 1924, pp. 10-12.

- ↑ Van der Waag, The Battle of Sandfontein, First World War Studies 4(2), 2013, pp. 143-145.

- ↑ General Staff: The Union of South Africa and the Great War, Pretoria 1924, pp. 12-13.

- ↑ Strachan, Hew: The First World War in Africa, New York 2004, p. 76.

- ↑ Collyer, Jack: The campaign in German South West Africa, 1914-1915, Pretoria 1937, pp. 20-21.

- ↑ Strachan: The First World War in Africa, New York 2004, pp. 63-64.

- ↑ Van der Waag, The Battle of Sandfontein, First World War Studies, pp. 146-147.

- ↑ Collyer, The campaign in German South West Africa, 1914-1915, pp. 13-20.

- ↑ Strachan: The First World War in Africa, New York 2004, p. 69.

- ↑ Nasson, Bill: Springboks on the Somme: South Africa in the Great War, 1914-1918, Johannesburg 2007, pp. 65-67.

- ↑ General Staff: The Union of South Africa and the Great War, Pretoria 1924, pp. 13-16.

- ↑ Van der Waag, The Battle of Sandfontein, First World War Studies 4(2), 2013, pp. 149-154.

- ↑ Nasson, Bill: Springboks on the Somme: South Africa in the Great War, 1914-1918, Johannesburg 2007, pp. 68-69.

- ↑ Collyer: The campaign in German South West Africa, 1914-1915, pp. 50-56.

- ↑ Van der Waag, The Battle of Sandfontein, First World War Studies 4(2), 2013, pp. 155-159.

- ↑ Collyer: The campaign in German South West Africa, 1914-1915, pp. 155-173.

- ↑ General Staff: The Union of South Africa and the Great War, Pretoria 1924, pp. 29-60.

- ↑ Strachan: The First World War in Africa, New York 2004, pp. 81-92.

- ↑ Nasson, Bill: Springboks on the Somme: South Africa in the Great War, 1914-1918, Johannesburg 2007, pp. 68-69.

Selected Bibliography

- Collyer, John Johnston: The campaign in German South West Africa, 1914-1915, Pretoria 1937: Government Printer.

- General Staff (ed.): The Union of South Africa and the Great War 1914-1915. Official history, Pretoria 1924: Government Printing and Stationary Office.

- Grundlingh, Albert M.: Fighting their own war. South African Blacks and the First World War, Johannesburg 1987: Ravan Press.

- Grundlingh, Albert M.: War and society. Participation and remembrance. South African Black and Coloured troops in the First World War, 1914-1918, Stellenbosch 2014: SUN Media.

- Heller, Charles E. / Stofft, William A.: America's first battles, 1776-1965, Lawrence 1986: University Press of Kansas.

- L'Ange, Gerald: Urgent imperial service. South African forces in German South West Africa, 1914-1915, Johannesburg 1991: Ashanti.

- Nasson, Bill: World War One and the people of South Africa, Cape Town 2014: Tafelberg.

- Nasson, Bill: Springboks on the Somme. South Africa in the Great War, 1914-1918, Johannesburg; New York 2007: Penguin.

- Paice, Edward: Tip and run. The untold tragedy of the Great War in Africa, London 2007: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Pakenham, Thomas: The scramble for Africa, 1876-1912, New York 1991: Random House.

- Park, M. H.: German South-West African Campaign, in: Journal of the African Society 25, 1916, pp. 113-132.

- Ploeger, Jan: The action at Sandfontein, 26 September 1914, in: Militaria 4, 1974, pp. 35-48.

- Rayner, W. S. / O'Shaughnessy, W. W. / Weinthal, Leo: How Botha and Smuts conquered German South West, London 1916: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co.

- Samson, Anne: World War I in Africa. The forgotten conflict among the European powers, London; New York 2013: I. B. Tauris.

- Stejskal, James: The horns of the beast. The Swakop River Campaign and World War I in South-West Africa, 1914-15, Solihull 2014: Helion & Company Ltd.

- Strachan, Hew: The First World War in Africa, Oxford; New York 2004: Oxford University Press.

- Trew, Henry Freame: Botha treks, London 1936: Blackie & Son.

- Van der Waag, Ian: All splendid, but horrible. The politics of South Africa's second 'little bit' and the war on the Western Front, 1915-1918, in: Scientia Militaria. South African Journal of Military Studies 40/3, 2012, pp. 71-108.

- Van der Waag, Ian: Smuts's generals. Towards a first portrait of the South African High Command, 1912-1948, in: War in History 18/1, 2011, pp. 33-61.

- Van der Waag, Ian: The battle of Sandfontein, 26 September 1914. South African military reform and the German South-West Africa campaign, 1914-1915, in: First World War Studies 4/2, 2013, pp. 141-165.