Introduction↑

On the eve of the First World War, Ottomans were struggling to come to terms with how to live together in the face of the multivalent internal and external pressures that were threatening to tear society apart. Ottoman society stands in for the diverse reality of a multi-ethnic empire and its range of social, cultural, and economic forms that varied significantly across the Ottoman lands from southeastern Europe and North Africa to the Arabian Peninsula and the borders of Central Asia. The empire’s diverse peoples and cultures were united through their existence within the political boundaries of the Ottoman Empire. Whereas in previous centuries imperial subjects had enjoyed a high degree of regional and local autonomy, in the decades before the First World War the Ottoman state gained an increasing ability to impact the daily lives of Ottoman subjects, giving this shared existence greater significance. The Ottoman “eve of the First World War”, then, extends to longer-term historical dynamics that contributed to the empire’s social milieu in 1914, beginning with the debut of far-reaching modernizing reforms in the mid-nineteenth century.

The Long Eve of World War I↑

The late Ottoman Empire’s political and social climate on the eve of the First World War was shaped by liberal reforms beginning with the Tanzimat (1839-1876), and continuing during the Second Constitutional Period (1908-1918). While reform was taking place under pressure from European powers, the Ottoman state also viewed reform as the best way to regain full independence and ensure the survival of the state. The goal of securing the Ottoman Empire’s survival into the modern era was the driving force behind the Ottoman reforms, and this imperative of survival would also play a central role in the Ottoman decision to participate in World War I.[1]

The Ottoman Empire was perhaps the most cosmopolitan state in the world, with approximately 30 million subjects from a wide variety of backgrounds.[2] The empire was ethnically and linguistically diverse, with bilingualism and trilingualism commonplace, particularly in urban centers.[3] Religious background was the most salient category of identity in the empire. Muslims constituted the majority of the Ottoman population and most Muslims were Sunni, although other communities existed as well. About one third of Ottomans were Eastern Christians, with Armenians constituting a significant population.[4] Other Christian groups were also present, and the empire’s Jewish population was small but influential. The 1856 imperial decree of constitutional equality between all of the empire’s religious and ethnic groups led to rising tensions both among these groups and between minority communities and the state. Equality was fundamentally at odds with the foundations of the Ottoman state, which relied upon a claim to the caliphate for its legitimacy, and functioned by privileging Muslim subjects for key positions within the bureaucracy and military.

The Ottoman Empire came late to industrialization, and manufacturing failed to contribute significantly to the economy by the outbreak of the First World War. By the mid-nineteenth century, the state had established several small industrial parks on the outskirts of Istanbul with factories producing garments, ammunition, paper, shoes, silk, steel, and other important commodities. The state policy of promoting domestic industry while simultaneously lowering tariffs and opening the Ottoman market to European goods made these local factories untenable without heavy state subsidies, and manufacturing did not thrive. Protectionist policies were eventually implemented but it was too little too late; although the Ottoman manufacturing sector was able to achieve a modest revival in the 1870s, industry remained a minor contributor to the state economy when compared with Europe.[5]

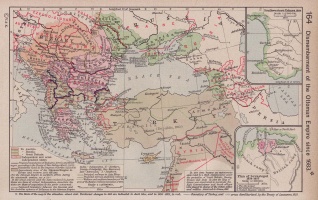

The nineteenth century modernization of Ottoman statecraft, infrastructure, and institutions entailed rapid state centralization that simultaneously undermined existing decentralized power arrangements and necessitated greater governmental intervention in the daily lives of Ottoman subjects both in Istanbul and the provinces. State centralization resulted in growing resentment among ethnic and religious minorities accustomed to overseeing their own affairs with minimal intervention from the central authorities. This increased contact with the state was frequently interpreted as an attack on local power hierarchies and, particularly in the non-Turkish speaking regions of the empire, as an outside attempt to subvert traditional social and cultural practices. The era that was supposed to witness the redoubling of Ottoman unity instead saw the greatest territorial losses in Ottoman history: between 1878 and 1913, the empire lost to independence and rival powers the majority of its European provinces, several Arab provinces and a handful of islands and border cities.[6]

The policies of Abdülhamid II, Sultan of the Turks (1842-1918) also contributed to the deterioration of intercommunal relations in the Ottoman Empire. Having come to power in the midst of major rebellions in the empire’s Balkan territories and just before the Eastern Crisis following upon the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878), Abdulhamid adopted autocratic policies designed to restore order and suppress dissent among restive groups in the empire. While continuing to embrace the idea of Ottomanism in theory, Abdulhamid also promoted pan-Islamism as a source of unity in the empire, alienating religious minority populations while reinforcing the preeminent position of Muslims in the imperial social hierarchy. Abdulhamid and his government were particularly concerned about the empire’s Armenian population, which was highly concentrated along the border with the Russian Empire. Numerous massacres of Armenian Christians took place under his watch, including the Hamidian Massacres of 1895-1896 that left up to 300,000 dead.[7]

The intersection of state-driven modernizing reforms and the policies of Sultan Abdulhamid II set in motion currents of social change that would crystallize on the eve of World War I. Centralizing reforms exposed more citizens to the contours of the state and their fellow Ottomans. While in many cases these encounters enhanced feelings of a collective Ottoman identity, increased contact with different peoples and places also threw group identities into relief, simultaneously strengthening awareness of the differences among Ottomans while compelling their allegiance to a shared set of goals and practices.

Ottoman Society Before World War I↑

The year 1908 constituted a turning point in the long nineteenth century process of modernization and social conflict in the Ottoman Empire. The Young Turk Revolution (1908-1909) marked the end of Abdulhamid II’s authoritarian rule and the return of constitutional governance to the empire. This was a moment when reconciliation between the state’s need to centralize and modernize to maintain sovereignty, and the local concerns of the empire’s diverse populations, seemed possible through liberal constitutionalism and Ottomanism. Even the outbreak of war in 1914 did not render this vision of Ottoman society an impossible dream; it was only in 1915-1916, when state-led brutality led to an irreconcilable rift between the Ottoman state and its minority subjects, that the dissolution of the empire became inevitable.

The reintroduction of constitutional governance created space for the empire’s diverse populations to express group interests in a variety of ways. In addition to constitutionalism, Ottoman subjects experimented with ideologies including Turkism, Arab nationalism, pan-Islamism and anti-imperialism.[8] Ottoman subjects expressed their political aspirations in a variety of ways on the eve of the First World War. Ottomans read and published books, journals and newspapers in various languages, participated in public demonstrations and boycotts, and contributed to popular subscriptions to fund the purchase of battleships.[9] Ottomans also formed associations to give collective voice to various interests and identities, participated in public debates, voted in elections, and served in the Ottoman parliament. The tone and content of political participation varied somewhat between Istanbul and the provinces. In Istanbul, Ottoman political views were frequently militaristic and anti-imperial, and spanned Islamist and Turkist perspectives.[10] In the Arab provinces, militarism was less pronounced and attitudes towards European powers were more diverse.

Liberal groups were active in the capital and Anatolia, with women, minorities, workers, and Ottoman elites embracing liberal stances, especially administrative decentralization, before and after the 1908 revolution. The League of Private Initiative and Decentralization, founded in 1905 by Sabahaddin Bey (1879-1948), advocated administrative decentralization and worked closely with Armenian revolutionary groups.[11] On the other hand, the foremost Armenian group, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) cooperated with the Young Turks in 1908, despite significant ideological differences, and non-Turkish Muslims found common cause with the Young Turks’ pro-Muslim agenda.[12] The 1909 counterrevolution involved a diverse coalition of old regime supporters, Islamists, liberals, and non-Turkish nationalists. The Liberal Entente, founded in 1911, continued the liberal challenge to Young Turk rule with renewed strength, bringing together diverse elements from the ulama to non-Muslim liberals.[13]

Public discussion of women’s rights and roles flourished during this period, encouraged by the Young Turk regime’s emphasis on the need to “liberate women from the shackles of tradition”.[14] Women, particularly those in urban areas, gained greater access to public space and enjoyed more opportunities for civic engagement, education, and professional development. The first female doctors, lawyers, and civil servants appeared during this period, and a flourishing women’s press, with new titles such as Kadin appearing in Istanbul after 1908 and al-Hasna in Beirut, provided the means for Ottoman women to express their ideas and opinions in a public forum.[15] At least a dozen new women’s organizations were founded between 1908 and 1916 in Istanbul. Some focused on areas like education and culture where women had established themselves over the past several decades, but others sought to expand the boundaries of women’s participation in Ottoman society.

While this era saw enhanced participation by women in public life, women taking up elite professions and engaging in militant political activism remained a minority in Ottoman society. For middle class urban women, a changing relationship to state and society was more fundamentally impacted by the reimagining of the domestic space as a realm of social citizenship, a process that had been taking shape since the late nineteenth century.[16] While simplicity and modesty was emphasized in this new conception of middle class taste, domestic consumption soared as families acquired the trappings of modernity necessary to locate themselves within the upwardly-mobile middle classes of the turn-of-the-century Ottoman Empire. Inexpensive but significant items such as handkerchiefs, vases, ashtrays, and goblets, imported from Europe, fulfilled this need.[17] Despite growing currents of militarism and anti-imperialism in Ottoman society, demand for imported items soared and middle class consumption patterns became more fully entrenched on the eve of the First World War.

From Diplomacy to War↑

The desirability of European goods did not signal an overarching sympathy toward Europe on the part of Ottoman society during this period. The loss of Ottoman Libya to Italy in 1911 and the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 reinforced an Ottoman sense of betrayal by Europe and its systems of international law and diplomacy originating in the nineteenth century, and highlighted the potential benefits of a military approach to the empire’s geopolitical problems. The Ottomans viewed themselves as victims of European aggression and popular sentiment supported militarism as the only way to resist the further encroachment of Europe into the Empire.[18] This faith in the opportunities presented by militarism was strengthened by the Ottoman recovery of Edirne by military means in 1913.

The Balkan Wars and the rise of anti-Western sentiment in the Ottoman Empire provided an opportunity for the Young Turk government to introduce an economic policy more in line with their Etatist and Turkist belief system. After 1914 the government embraced the concept of “National Economics”, a composite of corporatism, protectionism, and strict state regulation. The unilateral abrogation of the capitulations in September 1914 and the outbreak of World War I facilitated the development of a protectionist economy that privileged the interests of Muslim Turks. However, the wartime conscription of nearly half the empire’s adult male population, and military requisition of major means of transport caused domestic production to lag and created difficulties in getting locally-produced goods to market. As the war progressed, the Young Turk government made the encouragement of a Muslim Turk-dominated economy official policy, openly advocating the creation of a Muslim bourgeois class and working to achieve this by helping entrepreneurs launch new enterprises and creating Muslim trade organizations.[19] While the war negated many of the economic gains achieved, the Young Turk policy of national economics fostered a structural change in the economic hierarchy of the Ottoman economy by 1918.[20]

The Balkans played a pivotal role in the Ottoman Empire’s identity and geopolitical strategy. The desire to retain the Balkans drove Ottoman state policy during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, particularly the Tanzimat reforms, which aimed to secure the empire’s hold over its Balkan territories through reform and entry into the Concert of Europe.[21] The Balkans were also notable in having produced key leaders that would see the empire through its final years. Balkan-born Ottomans spearheaded the 1908 Young Turk Revolution and launched it from Macedonia.[22] The members of the “triumvirate” that led the Empire during World War I, Ismail Enver Pasha (1881-1922), Ahmed Jemal Pasha (1872-1922), and Mehmed Talat Pasha (1874-1921), were of Balkan origin. The first president of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal (1881-1938), was born in Salonica. The loss of the majority of Balkan territories in the Balkan Wars forced a complete reorientation of the empire away from Europe and towards the remaining Anatolian and Arab provinces. Ultimately, the Balkan Wars shaped the Ottoman Empire’s engagement with Europe and its fortunes during World War I. Determined to secure a formal alliance based on mutual interest rather than vague guarantees of sovereignty, the empire eventually aligned with Germany, sealing its fate.

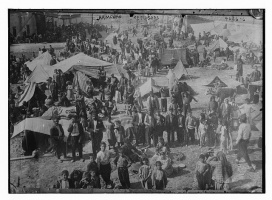

The social effect of the Balkan Wars in the Ottoman Empire was immediate and serious. Hundreds of thousands of refugees came pouring into Anatolia in the wake of the conflict, with gruesome tales to tell about the atrocities being committed against Muslims in the Balkans.[23] This led to rising anti-European sentiment in the empire and impatience with strategies of diplomacy and compromise that so far had led only to territorial loss and humiliation for the Ottomans. Furthermore, Ottomans began to call into question the empire’s ongoing protection of non-Muslim communities in Anatolia in light of what had happened, especially as Muslim refugees now needed homes and jobs. Ultimately, the Balkan Wars and their aftermath led to a hardening of divisions between religious groups and a popular perception that diplomacy had failed and that successful participation in a European conflict was the only way to firmly establish and secure Ottoman sovereignty.

The Ottoman Empire’s Arab subjects experienced these events somewhat differently. From the perspective of the provinces, the inability of the Ottomans to retain Libya and the Balkans pointed to a troubling lack of military power and administrative weakness. This led certain groups to begin considering where to turn if the Ottomans proved incapable of continuing to protect their Arab territories. For some, this meant beginning to think about independence, while others saw France and England as potential saviors.

As the First World War approached, it became increasingly clear that there was an irreconcilable divide between how civil society in Istanbul and the provinces viewed the Empire’s potential participation in the conflict.[24] In Istanbul, war was seen as an opportunity to gain long-sought independence from European pressure and emerge as a more unified, liberal, and modern polity. For this reason, emphasis was placed on popular social participation in the mobilization process.[25] While ostensibly inclusive of the entire empire, this process seemed mainly concerned with the Turkish-speaking populations of Anatolia.

In the Arab provinces, where European involvement in the future of the empire was received more favorably, participation in the war alongside Germany was viewed negatively. While the empire’s Turkish population could feel that there was something to gain from the conflict in the form of independence, the Arab population anticipated extreme sacrifice for the sake of an empire, the benefits of which grew less and less clear as the war got underway. On the eve of the First World War, then, a fundamental rift had already begun to appear between the Arab provinces and the Anatolian heartland of the Ottoman Empire. While still united under the dual banners of Ottomanism and Islam, war seemed to offer distinct opportunities and threats for different categories of Ottoman subjects.

Conclusion↑

Ottoman reform in the nineteenth century had failed to forge the social unity necessary to see the Ottoman Empire through the First World War intact. Although major rifts along ethnic, religious, and regional lines had become undeniable, the empire’s downfall was not a foregone conclusion in 1914. Rival ideologies, from nationalism, to decentralization, to pan-Islamism, were competing with each other for preeminence on the eve of the war, but this did not yet necessarily entail a break with the idea of Ottomanism. The pressures of war and expectations about its outcome would force the priorities and interests of the Ottoman state into the open as the conflict continued. It was only in 1915, when the genocide of Ottoman Armenians and iconic executions of Arab nationalist leaders took place, did the possibility of joint citizenship in an Ottoman state vanish for good. The Ottoman Empire’s inclusiveness had accommodated the possibility of religious, ethnic, regional, and political diversity in times of peace, but this complex inclusiveness, and the anxieties and conflicts it gave rise to, would ultimately unravel the webs of connections that had tied Ottoman society together for centuries.

Kate Dannies, Georgetown University

Section Editors: Elizabeth Thompson; Mustafa Aksakal

Notes

- ↑ Aksakal, Mustafa: The Ottoman Road to War in 1914. The Ottoman Empire and the First World War, Cambridge 2010.

- ↑ Hanioğlu, M. Şükrü: A Brief History of the Late Ottoman Empire. Princeton 2008, p. 24.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 33.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 25.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 93.

- ↑ Aksakal, The Ottoman Road to War in 1914 2010, p. 5.

- ↑ Estimates range between 80,000 and 300,000 dead. See: Akçam, Taner: A Shameful Act. The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility, New York 2006, p. 42.

- ↑ Kayali, Hasan: Arabs and Young Turks. Ottomanism, Arabism, and Islamism in the Ottoman Empire, 1908-1918, Berkeley 1997.

- ↑ Aksakal, Mustafa: Not by those old books of international law, but only by war. Ottoman Intellectuals on the Eve of the Great War, in: Diplomacy and Statecraft 15/3 (2004), p. 511.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 515.

- ↑ Hanioğlu, A Brief History 2008, pp. 146-147.

- ↑ Der Matossian, Bedross: Shattered Dreams of Revolution. From Liberty to Violence in the Late Ottoman Empire, Stanford 2014, pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Hanioğlu, A Brief History 2008, pp. 154-155.

- ↑ Women’s groups took on a greater social and political dimension during the Young Turk era. Although in existence since 1867, early groups had focused mainly on cultural and educational activities. See: Safarian, Alexander: On the History of Turkish Feminism, in: Iran and the Caucasus 11/1 (2007), pp. 141-151.

- ↑ Abou-Hodeib, Toufoul: Taste and Class in Late Ottoman Beirut, in: International Journal of Middle East Studies 43/1 (2007), p. 479.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 479.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 485.

- ↑ Aksakal, Mustafa: Holy War Made in Germany? Ottoman Origins of the 1914 Jihad, in: War in History 18/2 (2011), pp. 194-195.

- ↑ Hanioğlu, A Brief History 2008, pp. 189-190.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 190-191.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 60-61.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 149.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 173-174.

- ↑ Tamari, Salim: Year of the Locust. A Soldier’s Diary and the Erasure of Palestine’s Ottoman Past, Berkeley 2011.

- ↑ Besikci, Mehmet: The Ottoman Mobilization of Manpower in the First World War. Between Voluntarism and Resistance, Leiden 2012.

Selected Bibliography

- Abou-Hodeib, Toufoul: Taste and class in late Ottoman Beirut, in: International Journal of Middle East Studies 43/3, 2011, pp. 475-492.

- Aksakal, Mustafa: Not ‘by those old books of international law, but only by war'. Ottoman intellectuals on the eve of the Great War, in: Diplomacy and Statecraft 15/3, 2004, pp. 507-544, doi:10.1080/09592290490498884.

- Aksakal, Mustafa: The Ottoman road to war in 1914. The Ottoman Empire and the First World War, Cambridge 2008: Cambridge University Press.

- Aksakal, Mustafa: 'Holy war made in Germany'? Ottoman origins of the 1914 jihad, in: War in History 18/2, 2011, pp. 184-199.

- Beşikçi, Mehmet: The Ottoman mobilization of manpower in the First World War. Between voluntarism and resistance, Leiden 2012: Brill.

- Brummett, Palmira Johnson: Gender and empire in late Ottoman Istanbul. Caricature, models of empire, and the case for Ottoman exceptionalism, in: Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 27/2, 2007, pp. 281-300.

- Deringil, Selim: The well-protected domains. Ideology and the legitimation of power in the Ottoman Empire, 1876-1909, London 2011: I. B. Tauris.

- Der Matossian, Bedross: Shattered dreams of revolution. From liberty to violence in the late Ottoman Empire, Stanford 2014: Stanford University Press.

- Doumanis, Nicholas: Before the nation. Muslim-Christian coexistence and its destruction in late Ottoman Anatolia, Oxford 2013: Oxford University Press.

- Fortna, Benjamin C.: Imperial classroom. Islam, the state, and education in the late Ottoman Empire, New York 2002: Oxford University Press.

- Gingeras, Ryan: Sorrowful shores: Violence, ethnicity, and the end of the Ottoman Empire, 1912-1923, Oxford 2009: Oxford University Press.

- Hanioğlu, M. Şükrü: A brief history of the late Ottoman Empire, Princeton 2008: Princeton University Press.

- Hanssen, Jens: Fin de siècle Beirut. The making of an Ottoman provincial capital, Oxford 2005: Clarendon Press.

- Kandiyoti, Deniz: End of empire. Islam, nationalism and women in Turkey, in: Lewis, Reina / Mills, Sara (eds.): Feminist postcolonial theory. A reader, New York 2003: Routledge, pp. 263-284.

- Kayalı, Hasan: Arabs and Young Turks. Ottomanism, Arabism, and Islamism in the Ottoman Empire, 1908-1918, Berkeley 1997: University of California Press.

- Rogan, Eugene L.: Frontiers of the state in the late Ottoman Empire. Transjordan, 1850-1921, Cambridge; New York 1999: Cambridge University Press.

- Rogan, Eugene L.: Asiret Mektebi. Abdülhamid II's School for Tribes (1892-1907), in: International Journal of Middle East Studies 28/1, 1996, pp. 83-107.

- Tamārī, Salīm: Year of the locust. A soldier's diary and the erasure of Palestine's Ottoman past, Berkeley 2011: University of California Press.