Introduction↑

The Second International was composed of members of the socialist parties from European and non-European countries. This article focuses exclusively on the French, German and Italian socialists’ opposition to the war.

Between 1889 and 1914, French and German socialists often had similar opinions concerning questions of war and peace. Then, in August 1914, both countries entered the war and in both countries parliamentary socialists voted in favor of war credits. The Italian case is particularly interesting: although Italian socialism was strongly inspired at birth by German and later by French socialism, Italy remained neutral until 1915.

A Socialist Pacifism?↑

Questions of war and peace preoccupied French, German and Italian socialists in the years before World War I. They devoted much effort to preventing the war. In light of subsequent events, this commitment has been interpreted as a failure. However, the issue is more complex.

French and German socialists both voted for war credits on 4 August 1914. Italy entered the war a year later, on 24 May 1915. Even if a faction of the Partito Socialista Italiano (PSI) remained faithful to the ideals of peace, it lost some of its most important members, who left the party because of their interventionist stances.

In light of a more nuanced picture, no straightforward claim can be advanced as to the failure of the Second International’s socialists’ pacifism. The reason is simple: they were not for keeping the peace at all costs.

Pacifism↑

The socialists of this period did not call their anti-war engagement “pacifism”. They preferred to use expressions like “opposition to war”, “war to war”, or “anti-militarism” as a means to delineate the specificity of their thoughts and actions.

The new Socialist International and the war↑

The new International was created to again provide socialism with an international organization. The theoretical opposition to war had been on its agenda since the founding congress in Paris (14-19 July 1889), though it had not been considered a priority. The congress had instead concentrated mainly on questions such as the improvement of working conditions and work regulations. The first real discussions on opposition to war took place at the Amsterdam Congress (14-20 August 1904), in the midst of the Russian-Japanese War. As a consequence of the continuing international diplomatic crises and with the international situation worsening, war was gaining momentum as a topic of discussion within the International. A heated debate on the legitimacy of a general strike as a means to oppose war occupied a large part of the Congresses of Stuttgart (18-24 August 1907) and Copenhagen (28 August-3 September 1910). The Congress of Basel (24-25 November 1912), which took place during the First Balkan War (8 October 1912-30 May 1913), is considered to be the biggest socialist manifestation against war. Within the various countries, the exponents of French, German and Italian socialism also intensified their discussions and propaganda against war.

The socialist opposition to war and its limits↑

While the opposition to war became more important over time, socialists in Germany, France, and Italy defended a multitude of ideas about war, discussing topics such as how to oppose it, peace, militarism, and the fatherland. The idea of peacekeeping at all costs was not expounded by the Second International’s socialists.

The Prevention of War: International Arbitration and Ministerial Participation↑

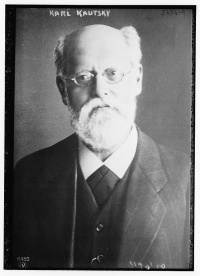

Jean Jaurès (1859-1914), leader of the Section Française de l’Internationale Ouvrière (SFIO), supported the attempt to prevent war through international arbitration. He planned an international tribunal that could act as a mediator between two or more nations in case of tensions. The socialists’ participation in the government of their nation was regarded as another way of opposing war. The matter was highly debated in Italy in 1911, at the beginning of the Italian-Turkish War (29 September 1911 – 18 October 1912). At the time, the PSI supported the government of Giovanni Giolitti (1842-1928). At the Congress of Modena (15-18 October 1911), however, the left-reformist wing maintained that the party should withdraw its support of Giolitti. This was meant to be a consequence of his decision to bring about war. Yet, the right-reformist wing claimed the opposite: as they saw it, the socialists had to struggle for peace, but in the event of war, they had to support their own fatherland – as Angiolo Cabrini (1869-1937) said. Within these three countries, the biggest discussions about ministerial participation took place at the Congress of Amsterdam, where Jaurès and Karl Kautsky (1854-1938) battled on the issue. Even though the discussion did not revolve around peace or war, understanding it is crucial to comprehending the future attitude of the International towards war. Kautsky accepted socialist participation in bourgeois government in some cases – in case the fatherland was in danger, for instance. In contrast, Jaurès claimed that he could not subscribe to what he termed Kautsky’s “nationalist ministerialism”. On that occasion, Kautsky, one of the most important theoreticians of German social-democracy, was already admitting the principle which was to inspire the attitude of the socialists on both sides of the Rhine in August 1914.

The Reaction to War: A General Strike↑

However, if war broke out, some socialists planned to enact a general strike to stop the conflict and to transform it into a proletarian revolution. Long discussions on the issue took place at the Seventh Congress of the Second International (the Congresses of Stuttgart). Four resolutions were proposed, including Gustave Hervé’s (1871-1944) resolution, which called for a general strike in case of war; it was, however, suddenly rejected because it was so extreme. Nevertheless, it was discussed at length in the subsequent days of the Congress. The resolution proposed by Jules Guesde (1845-1922) was also rejected. He did not call for any specific action against militarism. He held the opinion that militarism was a natural consequence of capitalism, and that the former could come to an end only when the latter ended. The assembly discussed two more moderate resolutions, one proposed by Jaurès and Édouard Vaillant (1840-1915), member of the SFIO, and the other by August Bebel (1840-1913), member of the SPD. Eventually, the congress adopted an amended version of the latter. Although it did not envisage a general strike, it enjoined all socialists to exploit war to bring about the social revolution.

The discussion was not finished. At the next congress of the Second International (Copenhagen, 26-27 August 1910), Vaillant and James Keir Hardie (1856-1915), a member of the British Labour Party, proposed a new resolution, which called for a general strike in case of war, in order to simultaneously paralyze mobilization in the relevant countries. This time the delegates agreed that it was necessary to discuss the resolution, but decided to defer that to the next congress, on August 1914. However, that never happened as by then war had already broken out.

The Fatherland and its Defense↑

The majority of the socialists did not deny their patriotism, even if they proclaimed themselves to be internationalists. Jaurès combined socialist universalism with his love for France: the fatherland was to be defended in case of danger – as Bebel also claimed. Anna Kuliscioff (1857-1925) and Filippo Turati (1857-1932), the reformist leaders of the PSI, held that reformist socialists should be in charge of national defense and should work to reform the army, although without abolishing it (later, in 1914-1915, Turati was to become a indefatigable partisan of Italian neutrality, opposing the revolutionary wing of the PSI, which championed the Italian participation in the war). However, Italian reformist socialism did not abandon the struggle against the expansion of military credits and the arms race.

Even though there was opposition within the three socialist parties – e.g. Hervé in France, Karl Liebknecht (1871-1919) and Rosa Luxemburg (1871-1919) in Germany, and Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) in Italy – the ideas of patriotism and the defense of the fatherland were shared by many of their members. Their antimilitarist and patriotic stances could be added to the idea of the abolition of the permanent army and of its substitution with armies composed of citizens. These would be composed of citizens rather than professional soldiers and their only goal would be the defense of their country. The most complete description of its characteristics and workings can be found in a 1911 book by Jaurès: L’armée nouvelle. A similar model had been championed by the SPD since its founding. The Erfurt Program of 1891 had envisioned a Volkswehr (an army composed of citizens) and underlined the necessity of the allgemeine Volksbewaffnung (general arming of the people).

In conclusion, peace-keeping remained a central question in the debates of French, German and Italian socialists in the last decade before World War I. However, many of them were not ready to sacrifice the ideals of the fatherland and its defense for the ideals of international peace. And that is what happened in 1914.

Elisa Marcobelli, German Historical Institute Paris

Section Editor: Emmanuelle Cronier