Introduction↑

Most European nations commemorate the end of World War I on 11 November, the anniversary of the armistice on the Western Front. Recent scholarship proves, however, that, particularly in East Central Europe, the war did not end in 1918, but instead transformed into a series of violent conflicts and minor wars. The experiences of war veterans in this region of the continent during this period contributed to the radicalization of interwar political cultures. Hungary is undoubtedly not an exception in this regard.[1] This essay focuses on those turbulent years, examining the demobilization of soldiers and the rise of different (local, left- and right-wing) formations, and discusses the fate of paramilitary leaders in the interwar period.

Homecoming and Demobilization↑

The regiments recruited from the territory of the Hungarian Kingdom fought in the Habsburg army on all of the monarchy’s front lines in World War I. Despite the repeated demands of the Hungarian political elite before 1914, these units were subordinated to the unified military command of the k. u. k. Armeeoberkommando (AOK). After the successful Aster Revolution on 31 October 1918, Mihály Károlyi (1875-1955) seized power in Budapest. The revolutionary coalition government promised the end of hostilities and declared complete independence from Austria by dissolving the Pragmatic Sanction. Béla Linder (1876-1962), the newly appointed minister of war, proclaimed his authority over every military formation recruited from the territory of the Hungarian Kingdom. He ordered the AOK to immediately withdraw these troops from the front. Partly thanks to these orders, most of the Hungarian regiments left the front lines sooner than their Austrian comrades, contributing to the final dissolution of the common Habsburg Armed Forces.[2]

Despite their early departure, the troops’ homecoming was very slow and lasted until the end of November 1918. During this month, 1.3 million soldiers arrived in Hungary, less than 30 percent of whom travelled under the leadership of their officers. The Balkan and reserve army units dissolved particularly quickly, while the regiments returning from the Italian and French front lines remained more disciplined. Although the respective national councils had already seized power in many capital cities of Austria-Hungary and proclaimed their own nation states, these developments often had little impact on the returning troops. The cohesion of many multi-ethnic units remained relatively stable on the journey home and only dissolved upon arrival at their home garrisons.[3]

Budapest undoubtedly made massive efforts to demobilize these returning soldiers. Although the government proclaimed itself revolutionary and advocated a complete break with the Habsburg past, the Hungarian war ministry mostly carried out plans developed by the imperial administration during World War I. Demobilization stations were established and major railway hubs were reinforced with troops and food supplies. Additional payment was offered to soldiers in exchange for their weapons. Despite all these efforts, only around half of the returning servicemen appeared at the demobilization stations. The turnout was significantly higher in the central regions of the country than in the multi-ethnic border regions, particularly in Transylvania and eastern Hungary.[4]

Violence, Popular Unrest, and Local Remobilization↑

Many returning soldiers participated in the popular unrest beginning in early November 1918. The returning servicemen attacked manor houses, food stores, and representatives of state authority. In certain regions, especially in eastern Hungary, these attacks had a strong anti-Semitic character. Locals considered the Jewish merchants war profiteers who were responsible for the food shortage during the war. The peasant uprisings in the countryside – particularly in the eastern and northern regions of the country – were reinterpreted in ethnic terms. The landowners and representatives of the state were mostly Magyars, while the peasants were mostly Slovaks, Ukrainians, and Romanians.[5]

The massive violence in the countryside provoked a quick remobilization by the Károlyi government. Conscription was maintained and the youngest enlisted soldiers (born between 1896 and 1900) were deployed against the rioters. This, however, turned out to be relatively ineffective, since only 37,000 people remained in service at the end of November 1918. In contrast to the unsuccessful remobilization of the regular army, several local paramilitary formations appeared all over in the countryside. These units – mostly financed by local landlords and dignitaries – engaged in combat with the rioters and sometimes even with each other. The government quickly started to regulate these troops and established the umbrella organization of the national guard (Nemzetőrség). The members of these squads were largely older reserve soldiers, already discharged from the army before 1918. They mostly served part-time and kept their normal civilian job. They were led by reserve officers who were mostly representatives of the local elite. In many villages the national guards were simply renamed versions of the local gendarmerie squads or volunteer fire fighter squadrons. Due to the relatively good remuneration, the size of these units increased significantly and reached 100,000 men at the end of November. In Transylvania, separate Romanian and Saxon national guards were established, which mostly did not obey orders from Budapest. They acted independently and only accepted the leadership of the local Romanian and Saxon national councils. The national guard system, however, turned out to be both ineffective and very expensive. In late 1918, the Károlyi government began to dismantle these formations. The majority of the soldiers simply returned to their normal life, while many eastern Hungarian squads were merged into regular army units and deployed against the advancing Romanian troops.[6]

Regional Paramilitary Units, Székely Division↑

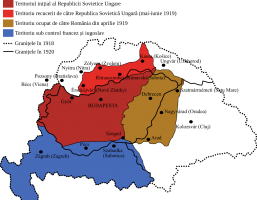

As in many other parts of East-Central Europe in 1918-1919, not only were local paramilitary forces established, but some units even adopted a strong, often invented, provincial identity. In Hungary, the most important “regional” formation of this period was the so-called Székely (or Szekler) Division.[7] It was founded under the leadership of Károly Kratochvil (1869-1946) in Transylvania during the winter of 1918. Kratochvil was a professional army officer born in a traditional Habsburg military family and was appointed head of the Transylvanian military district at the end of November 1918. He began to recruit and reorganize the local self-defence formations and merged the remains of the regular regiments and national guards together.[8] Although the soldiers recruited from the Szeklerlands were in a clear minority, the military leadership began to promote this special “regional” character during the winter of 1918. This identity was used to enhance the troops’ morale and to gain support from the political elites of Budapest. Their efforts were relatively effective; by spring 1919, the division had become the largest Hungarian armed unit on the Eastern Front.[9] Due to the constant Romanian advance in Transylvania, the division was withdrawn from Kolozsvár (Cluj) to the Zilah-Csucsa-Zám (Zalău-Ciucea-Zam) line, where it took up a defensive position. During winter 1919, the unit was engaged in several skirmishes with Romanian forces. The weakened division was finally destroyed in mid-April 1919, when the vast majority of the Székely soldiers – including Kratochvil – surrendered to the Romanian army. A smaller part remained in the Red Army and a few officers later joined Miklós Horthy’s (1868-1957) white forces in Szeged.[10]

The Red Army and Terror Groups↑

By March 1919, the Serbian, Romanian, and Czechoslovakian army had advanced deep into the territory of the historical Hungarian Kingdom. The prospect that Hungary could lose large parts of its land, together with the government’s inability to handle post-war crises, significantly undermined the legitimacy of the democratic regime. The lack of domestic and foreign political support led to the resignation of Károlyi and the Bolshevik takeover on 21 March 1919. The new communist-social democratic government immediately began to establish its own armed forces. In April 1919, they reorganized the old Habsburg regiments and an intense mobilization began after the start of the Romanian offensive on 16 April. The revolutionary government then decided to rely on its “natural supporters,” the organized workers. During the first weeks of May, mobilization was particularly successful in the industrial outskirts of Budapest. Trade union workers formed their own battalions, where colleagues from the same factories served together. These troops were mostly led by former professional Habsburg officers, who were called up in late April. The new and more powerful Red Army pushed the Czechoslovakian units back and occupied the major industrial town of Kassa (Košice) in early June 1919. After negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference, the Hungarian troops were forced to retreat to the original demarcation line. Consequently, the morale of the soldiers deteriorated and many disillusioned officers decided to resign.[11]

Meanwhile, villages rioted against the introduction of conscription and intensified food requisition. In order to counter these uprisings, the communist leaders decided to establish a new, loyal police force. The first so-called terror troops were founded in late March 1919 under the leadership of a young shoemaker, József Cserny (1892-1919). He was a former sailor who had returned to Hungary from revolutionary Russia in December 1918. Cserny and his paramilitary group were only loyal to certain communist leaders and completely disregarded the orders of the official state administration. Due to Cserny’s uncontrollable nature, the troops were disbanded and reorganized several times and finally subordinated to Otto Korvin’s (1894-1919) newly-formed political investigation department. Korvin, a well-educated bank clerk, was an active member of the anti-militarist movement before 1918. Despite his intellectual pacifism, he became the head of the secret police and firmly believed in the necessity of revolutionary violence.[12] Besides Cserny and Korvin, the third important figure of the Red Terror was Tibor Szamuely (1890-1919). Szamuely was appointed head of the so-called Home Front Committee after the beginning of the Romanian offensive. His men, the “Lenin boys,” were stationed in Budapest and travelled by armored train to the countryside to suppress any supposed “counterrevolutionary activity.” Gergely Bödők’s extensive research shows that the members of these terror squads came from a particular social background. They were mostly industrial workers and craftsmen in their mid-twenties, born in the central areas of Hungary. Although the interwar anti-Semitic propaganda often portrayed these groups as “Judeo-Bolshevik” guards, only around 20 percent of them came from Jewish families.[13]

The victims of the Red Terror were mostly peasants who resisted food requisition and refused to enlist to the army. In addition to that, in many places small landowners, priests, and former police officers, who were considered the natural enemies of the new regime, were also automatically executed. In Hungary, altogether 587 people were murdered by the Red Terror groups. Around half of them were executed as “counterrevolutionaries,” while the others were either killed in combat or hanged for “regular” crimes, like desertion or pillaging. Additionally, in the major towns, 500 members of the pre-war ruling elites were taken hostage.[14]

Despite these harsh terror measures, the communist regime became more and more unstable over the summer of 1919. As a last desperate attempt to gain popular support, Béla Kun (1886-1939) decided to launch a new offensive against the Romanian forces. The attack, which took place in July 1919, turned out to be a spectacular failure. The relatively weak Hungarian troops were defeated quickly and the Romanian army occupied Budapest on 4 August 1919.

The Counterrevolution and the Right-wing Paramilitaries↑

While the communist regime still ruled in Budapest, conservative political forces formed their own government in the southern Hungarian town of Szeged. During early June 1919, they appointed Admiral Horthy war minister of the new government. After a very short time, Horthy became the sole and most respected leader of the counterrevolution. Together with his deputy Gyula Gömbös (1886-1936), Horthy started to organize regular army units and officer detachments in late June 1919.[15] Two months later, around 3,000 more or less well-equipped soldiers were available for the “White Army.” Many of them were officers returning from Viennese exile or deserting the Red Army. After the collapse of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, these troops began to advance in the western part of the country and occupy the major towns in the countryside. Through conscription and the incorporation of former Red Army soldiers, the size of the National Army increased to 15,000 men and reached 100,000 soldiers in early 1920. The largest unit was Anton Lehár’s (1867-1962) – the brother of the composer Franz Lehár (1870-1948) – group, formed in western Hungary from former Honvéd regiments.[16] Horthy’s new force consisted of both “normal” and paramilitary formations. The line between these remained, however, very uncertain during the entire period. Many officers served in the regular army and were also active participants in radical right-wing associations like the Ébredő Magyarok Egyesülete (ÉME) and Magyar Országos Véderő Egylet (MOVE).[17]

The social background of the various paramilitary units differed fundamentally. Pál Prónay’s (1874-1947/1948) detachment was the most elite group. Many of his subordinates came from aristocratic or high-class families. Prónay himself was a baron who served with distinction in the war as a Hussar officer. While his squad had a rather high-class character, other paramilitary groups like Iván Héjjas’ (1890-1950) detachment were rooted in the rural elites of the Hungarian countryside. Héjjas, the son of a wealthy farmer, mostly recruited his men from the well-to-do peasants and public clerks from the area around the rural town of Kecskemét.[18] Pre-1990 scholarship often portrayed the members of these paramilitary groups as the losers of the social changes of the early 20th century. Recent scholarship, most notably from Béla Bodó, however, has proven that these people did not reject the ideas of modernity but more likely wanted to benefit from the elimination of their supposed rivals in the race for resources.[19]

The right-wing paramilitary groups roamed the countryside and acted independently from, but often with the silent approval of Horthy and the military headquarters. They entered various rural towns and villages and attacked former Bolshevik leaders, poor peasants and workers, whom they considered inherent supporters of communism. This violence had a strong anti-Semitic character and many Jews – regardless of their political views – fell victim to the atrocities. Most of the time they selected their targets arbitrarily, but often local conservative elites called on them to settle scores with their rivals. In some cases, however, the municipal authorities and local notables tried to stop the atrocities and defended their own peasants. This was more common after 1920, when local police forces became more reliable and powerful. According to different estimations, the White Terror’s victims numbered 1,000-1,200 people.[20]

Consolidation↑

After Horthy had been appointed by the National Assembly as the regent of Hungary on 1 March 1920, the often independent actions of the paramilitary leaders became more and more inconvenient for the consolidating regime. The murder of two social democratic journalists, Béla Bacsó (1891-1920) and Béla Somogyi (1868-1920), caused massive public outrage in the country. In addition to that, the regulations of the Treaty of Trianon restricted the Hungarian army to 35,000 soldiers. Consequently many of the veterans who were involved in the atrocities were discharged or temporarily sorted into the gendarmerie.[21]

The Indian summer of the paramilitary movement came in autumn 1921 during the Burgenland crises. Around 3,000 people, members of officer detachments and nationalist student associations, went to western Hungary under the leadership of Prónay. Although he had officially been discharged from the army, his unit was covertly supported by Budapest. After minor skirmishes, he forced out the weak Austrian troops from the area of Sopron (Ödenburg). Prónay, however, became a loose cannon, established his own puppet state in the beginning of October 1921 and refused to take orders from Budapest.[22] This turned out to be a decisive moment for the entire paramilitary movement. Due to their supposed “humiliation” by Budapest, many leaders, including Prónay and his deputy Gyula Ostenburg (1884-1944) decided to support Károly IV, King of Hungary’s (1887-1922) second attempt to return to the throne. Meanwhile others, most notably Gömbös and the student associations, remained loyal to Horthy. These hastily organized units defeated the loyalist forces in the Battle of Budaörs on 23 October 1921. Prónay, Ostenburg, and Lehár were discharged from the army for good, although they were never put on trial for their atrocities.[23]

Conclusion: The Long Shadows of 1918-1921↑

In Hungary, the post-war transition period only ended in late 1921, when the new autocratic Horthy regime finally consolidated itself. The Bolshevik and royalist forces were defeated and the right-wing paramilitary units were discharged. The leaders of the armed formations which dominated in that period, however, had quite different post-war careers.

The main figures of the Red Terror were put on trial and executed by 1919, with the exception of Szamuely, who committed suicide during his attempted escape from the country. In contrast, the officers of the Red Army were able to continue their careers almost uninterruptedly after 1919 in the National Army. Many of these men became prominent military leaders and close advisors to Horthy. For example, Henrik Werth (1881-1952) and Ferenc Szombathelyi (1887-1946) served as the chiefs of the Honvéd staff during World War II.[24]

Unlike regular army officers, up to the middle of the 1920s, the right-wing paramilitary leaders found themselves mostly on the peripheries of political life. This decade was mostly dominated by pragmatic liberal-conservative politicians like Prime Minister István Bethlen (1874-1946), who distanced themselves from the radical nationalists. The real change began in the early 1930s, when prominent paramilitary leaders were able to make their way into mainstream politics. Most notably, Gömbös’ populist “race defender” movement slowly took over the ruling conservative party from the inside. After his appointment as prime minister in 1932, many of his old comrades began to occupy key positions in the state administration.[25]

Not every former paramilitary leader, however, became integrated into the political mainstream of the 1930s. The royalist Lehár remained in Austrian exile, while others like Kratochvil were discharged from the army early on. Despite the fact that he was not born in Transylvania, Kratochvil became a prominent figure in the Budapest emigrant community in the 1920s. Although he was a committed nationalist, he always despised the radical right political movements. He remained an old-fashioned conservative through the 1930s and even used his influence to save Jews during World War II.[26]

Other leaders like Iván Héjjas and Prónay remained radical through the entire period and, in the 1930s, organized many small and insignificant right-wing opposition parties. In 1939, Héjjas was involved in the paramilitary actions of the so-called Rugged Guard during the occupation of Carpathian Ruthenia. Meanwhile, Prónay allied himself with the Arrow Cross Party and, in 1944-1945, fought in the Siege of Budapest.[27] Others played an even more important role in the radical right-wing movements of the 1940s. László Endre (1895-1946), the brain behind the deportation of the Hungarian Jews, was a veteran of the Burgenland conflict, while Döme Sztójay (1883-1946), the collaborator prime minister after the German occupation of 1944, was an officer in the Bolshevik Red Army.[28] Despite these prominent examples, members of post-World War I paramilitary movements were relatively underrepresented among the perpetrators of the Hungarian Holocaust. The majority of these people were simply too old to make an impact during the 1940s. The grim actions of the few still active, however, serve as an example of the sad legacy of the post-World War I period.

Tamás Révész, Hungarian Academy of Sciences

Section Editors: Gunda Barth-Scalmani; Richard Lein

Notes

- ↑ Gerwarth, Robert: Fighting the Red Beast. Counter-Revolutionary Violence in the Defeated States of Central Europe, in: Gerwarth, Robert / Horne, John: War in Peace. Paramilitary Violence in Europe after the Great War, Oxford 2012, p. 70.

- ↑ Rauchensteiner, Manfried: The First World War, Vienna 2014, p. 1005, 1008.

- ↑ See the reports in the Hungarian Military Archive. HL. P. d. f. B/4. d. 3627. 680. 11. 21., B/8. d. 3900. 12-27.

- ↑ HL. P. d. f. B/5. d. 3644. 102.

- ↑ Hatos, Pál: Az Elátkozott Köztársaság - Az 1918-as Összeomlás És Forradalom Története [The Damned Republic. The History of the Revolution and Collapse of 1918], Budapest 2018, pp. 180-183.

- ↑ Hajdu, Tibor: Az 1918-as Magyarországi Polgári Demokratikus Forradalom [The Bourgeoisie Democratic Revolution of Hungary in 1918], Budapest 1968, pp. 136-137; HL. P. d. f. B/4. d. 3587. 384. and B/5. d. 3641. 9.

- ↑ Szekler people, a sub-group of the Magyars, live in a language enclave in the eastern part of Transylvania. In the middle ages and the early modern period they were assigned to guard the eastern frontiers of the province. Until 1848, they held special privileges and constituted one of the three feudal nations of Transylvania, later to become pivotal in Hungarian nation-building in the region, especially due to their military efforts in 1848-1849.

- ↑ Barna, Gottfried / Nagy, Szabolcs: A Székely Hadosztály Története [The History of the Székely Divison], Miercurea Ciuc 2018, pp. 56-57.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 59.; Romsics, Ignác: Erdély Elvesztése, 1918-1947 [Losing Transylvania, 1918-1947], Budapest 2018, p. 240.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 248-249.

- ↑ Hajdu, Az 1918-as 1968, pp. 180-187.

- ↑ Konok, Péter: Erőszak kérdései 1919-1920-ban. Vörösterror-fehérterror [The Violence of 1919-1920. Red Terror-White Terror], in: Múltunk 55/3 (2010), pp. 72-91.

- ↑ Bödők, Gergely: A “proletárforradalom hűséges katonái” vagy “közönséges haramiák”? Kik voltak a “Lenin-fiúk”? ["Loyal Soldiers of the Proletarian Revolution" or "Common Criminals"? Who Were the "Lenin Boys"?], in: Múltunk 1 (2016), pp. 157-159.

- ↑ Bödők, Gergely: Vörös És Fehér. Terror, Retorzió És Számonkérés Magyarországon 1919-1921 [The Red and White Terror. Retaliation and Legal Repression in Hungary 1919-1921], in: Kommentár 3 (2011).

- ↑ Bodó, Béla: Paramilitary Violence in Hungary After the First World War, in: East European Quarterly 38/2 (2004), p. 139.

- ↑ Dombrády, Lóránd: A Legfelsőbb Hadúr És Hadserege [The Supreme Commander and His Army], Budapest 1990, pp. 7-8.

- ↑ Bodó, Paramilitary Violence 2004, pp. 147-153.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 143, 148.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 143, 163.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 154, 163.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 147-153.

- ↑ Bodó, Béla: Pál Prónay. Paramilitary Violence and Anti-semitism in Hungary, 1919-1921, in: Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East European Studies 2101 (2011), p. 31; Bodo, Paramilitary Violence 2004, pp. 147-153.

- ↑ See Bodó, Béla: Favorites or Pariahs? The Fate of the Right-Wing Militia Men in Interwar Hungary, in: Austrian History Yearbook 46 (2015), pp. 327-359.

- ↑ Szakály, Sándor: A Magyarországi Tanácsköztársaság Vörös Hadseregének tisztikara [The Officer Corps in the Hungarian Soviet Republic's Red Army], in: Palócföld 23/1 (1989), pp. 13-21.

- ↑ Romsics, Ignác: Istvan Bethlen. A Great Conservative Statesman of Hungary, Boulder 1995; Vonyó, József. Gömbös Gyula És a Hatalom. Egy Politikussá Lett Katonatiszt, Pécs 2018.

- ↑ Nagy, Szabolcs: A “Tiszteletbeli Székely” (Kratochvil Károly Közéleti Tevékenysége Trianon Után) [The "Honorary Székely" (The Public Actions of Károly Kratochvil After the Trianon Peace Treaty)], in: Székelyföld 5/1 (2009); Horváth, Ferenc Sz.: Kratochwill Károly És a Székely Hadosztály Egyesület Tevékenysége Az Észak-Erdélyi Zsidók Védelmében (1943-44) [The Role of Károly Kratochvil and the Székely Divison Association in the Protection of Jews in Northern Transylvania (1943-44)], in: Századok 1 (2018), p. 136.

- ↑ Bodó, Favorites or Pariahs? 2015, p. 344.

- ↑ Ibid., 355-357; Szakály, The Officer Corps 1988.

Selected Bibliography

- Barna, Gottfried / Nagy, Szabolcs: A Székely Hadosztály története (The history of the Székely Divison), Miercurea Ciuc 2018: Gutenberg Kiadó.

- Bodó, Béla: Favorites or pariahs? The fate of the right-wing militia men in interwar Hungary, in: Austrian History Yearbook 46, 2015, pp. 327-359.

- Bodó, Béla: Paramilitary violence in Hungary after the First World War, in: East European Quarterly 38/2, 2004, pp. 129-172.

- Bodó, Béla: Pál Prónay. Paramilitary violence and anti-semitism in Hungary, 1919-1921, in: Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East European Studies 2101, 2011.

- Bödők, Gergely: A 'proletárforradalom hűséges katonái' vagy 'közönséges haramiák'? Kik voltak a 'Lenin-fiúk'? ('Loyal soldiers of the proletarian revolution' or 'common criminals'? Who were the 'Lenin boys'?), in: Múltunk 1, 2016, pp. 122-159.

- Bödők, Gergely: Vörös És Fehér. Terror, Retorzió És Számonkérés Magyarországon 1919–1921 (The Red and White Terror. Retaliation and legal repression in Hungary (1919-1921)), in: Kommentár 3, 2011.

- Bódy, Zsombor (ed.): Háborúból Békébe. A Magyar Társadalom 1918-1924. Konfliktusok, Kihívások, Változások a Háború És Az Összeomlás Nyomán (From war to peace. The Hungarian Society 1918-1924. Conflicts, challenges, and changes after the end of WWI and the collapse of the state), Budapest 2018: MTA Bölcsészettudományi Kutatóközpont Történettudományi Intézet.

- Csunderlik, Péter: A 'vörös farsangtól' a 'vörös tatárjárásig'. A tanácsköztársaság a korai Horthy-korszak pamflet-és visszaemlékezés-irodalmában (From the 'red carnival' to the 'red barbarism'. The Hungarian Soviet Republic in the memoires and pamphlets of the Horthy era), Budapest 2018: Napvilág Kiadó.

- Dombrády, Lóránd: A legfelsőbb hadúr és hadserege (The supreme commander and his army), Budapest 1990: Zrínyi Kiadó.

- Gerwarth, Robert: The vanquished. Why the First World War failed to end, 1917-1923, London 2016: Allen Lane.

- Gerwarth, Robert: Fighting the red beast. Counter-revolutionary violence in the defeated states of Central Europe, in: Gerwarth, Robert / Horne, John (eds.): War in peace. Paramilitary violence in Europe after the Great War, Oxford 2012: Oxford University Press.

- Hajdu, Tibor: Az 1918-as magyarországi polgári demokratikus forradalom (The bourgeoisie democratic revolution of Hungary in 1918), Budapest 1968: Kossuth Könyvkiadó.

- Hatos, Pál: Az Elátkozott Köztársaság - Az 1918-as Összeomlás És Forradalom Története (The damned republic. The history of the revolution and collapse of 1918), Budapest 2018: Jaffa Kiadó.

- Horne, John / Gerwarth, Robert: Paramilitarism in Europe after the Great War. An introduction, in: Horne, John / Gerwarth, Robert (eds.): War in peace. Paramilitary violence in Europe after the Great War, Oxford 2012: Oxford University Press.

- Horváth, Ferenc Sz.: Kratochwill Károly És a Székely Hadosztály Egyesület Tevékenysége Az Észak-Erdélyi Zsidók Védelmében (1943-44) (The role of Károly Kratochvil and the Székely Divison Association in the protection of Jews in northern Transylvania (1943-44)), in: Századok 1, 2018.

- Konok, Péter: Erőszak kérdései 1919-1920-ban. Vörösterror-fehérterror (The violence of 1919-1920. Red terror-white terror), in: Múltunk 55/3, 2010.

- Nagy, Szabolcs: A 'Tiszteletbeli Székely' (Kratochvil Károly Közéleti Tevékenysége Trianon Után) (The 'honorary Székely' (the public actions of Károly Kratochvil after the Trianon Peace Treaty)), in: Székelyföld 5/1, 2009.

- Rauchensteiner, Manfried: The First World War and the end of the Habsburg monarchy, 1914-1918, Vienna 2014: Böhlau.

- Romsics, Ignác: Erdély Elvesztése, 1918-1947 (Losing Transylvania, 1918-1947), Budapest 2018: Helikon.

- Romsics, Ignác: István Bethlen. A great conservative statesman of Hungary, 1874-1946, Boulder 1995: Social Science Monographs.

- Schlag, Gerald: Aus Trümmern geboren. Burgenland 1918-1921, Eisenstadt 2001: Burgenländisches Landesmuseum.

- Szakály, Sándor: The officer corps of the Hungarian Red Army, in: Pastor, Peter (ed.): Revolutions and interventions in Hungary and its neighbor states, 1918-1919, Boulder et al. 1988: Social Science Monographs.

- Vonyó, József: Gömbös Gyula és a hatalom egy politikussá lett katonatiszt (Gyula Gömbös and the power. From an officer to a politician), Pécs 2018: Kronosz.