Early Career↑

Alexandre Millerand (1859-1943) was born in Paris in 1859. Trained as a lawyer, he started his political career as a journalist in Georges Clemenceau’s (1841-1929) daily La Justice. In 1885, Millerand, a radical republican at this time, was elected deputy. During his time in office, he moved left and, in 1887, became one of the founders of the socialist group in the French Chamber of Deputies. In the 1890s, he was one of its most prominent members; in 1896 he formulated the famous "Saint-Mandé program", a minimal consensus among the various socialist factions that paved the way for socialist unity at the beginning of the 20th century. When, at the height of the Dreyfus Affair, Millerand became minister of commerce in the centre-left government of René Waldeck-Rousseau (1899-1902), this provoked a major crisis in his party, with repercussions even in the Socialist International. In the following years, Millerand shifted to the right; he was excluded from his party in 1904 and subsequently figured as an "independent socialist".

War Minister in the Union sacrée↑

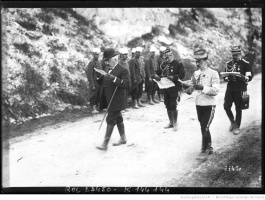

Even as a socialist, Millerand had always called himself a patriot; he approved of the Franco-Russian alliance and was critical of the growing anti-militarism and internationalism within his party. In the pre-war years, his nationalism grew steadily. Millerand thus became a suitable candidate for minister of war, a post he held twice, first in 1912-1913 under Raymond Poincaré (1860-1934), then again in 1914-1915 in René Viviani’s (1862-1925) government of the Union sacrée. During his first term in office, Millerand successfully strengthened the position of Joseph Joffre (1852-1931) as head of the general staff. During the war, Millerand considered it to be his first duty to protect Joffre and the high command from political (i.e. civilian) interference. Inside the government, he acted more and more as Joffre’s mouthpiece. He was responsible for the institution of the infamous special court-martials intended to tighten military discipline and stifle all signs of war-weariness and pacifism in the army. He also favored the institution of censorship to avoid bad news and public debate about the military situation. In the course of the war, Millerand had to face growing criticism from parliamentarians in both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. Beside his unwillingness to allow politicians to visit the front, the shortcomings of French arms production provoked the parliamentarians’ discontent that finally led to Millerand’s departure from the war ministry in October 1915.

After the War↑

After the war, Millerand continued his political career, first as commissioner-general of the republic for Alsace-Lorraine (1919-1920), then as head of government (Président du Conseil, 1920) and finally, from September 1920 to June 1924, as president of the republic. His project to reform the constitution in order to strengthen the executive failed; in 1924, the new left-wing majority in the Chamber of Deputies forced him to resign. In 1925, he was elected senator, but he ceased to play a significant role in French politics. On 7 April 1943, Millerand died in Versailles.

Daniel Mollenhauer, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München

Section Editor: Emmanuelle Cronier