Life and military career↑

Maximilian of Baden (1867-1929) was born on 10 July 1867, the son of Prince Wilhelm von Baden (1829-1897) and Maria Maximilianowna von Leuchtenberg (1841-1914). He studied law and joined the Prussian army. His uncle was Frederick I, Grand Duke of Baden (1826-1907). When it became apparent that Frederick’s son would remain childless, Max of Baden was told to secure the succession. Despite his homosexuality, he therefore married Maria Louise of Hanover (1879–1948) in 1900 and fathered an heir.[1]

At the outbreak of war, Baden served as a general staff officer at the XIV Corps. Even though he had no military responsibilities, he left his post after three weeks because of “nervous problems”. Instead he was made honorary president of the Baden section of the German Red Cross, where he focused on prisoner of war work using his international contacts. However, it was mainly due to the organisational skills of his associate Joseph Partsch (1882-1925) that his work was successful.

By 1915 Baden approached German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg (1856-1921) and offered to mediate with Russia. His aim was to achieve a peace agreement via his Russian relatives. He also hoped to lure Sweden out of its neutrality to increase pressure on Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1868-1918). His efforts failed.[2]

The Last Chancellor of Imperial Germany↑

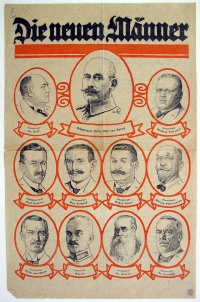

Max of Baden was first proposed as Chancellor in 1917. The political networker Kurt Hahn (1886-1974) was instrumental in creating an idealized image of Prince Max as a liberal modernizer. This was far from the truth,[3] but Baden saw the chance to play a heroic role. Eventually, when at the insistence of Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937) the Supreme Army Command (Oberste Heeresleitung, or OHL) demanded that the civilian government obtain an immediate ceasefire, Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) appointed Baden as Chancellor in place of the aging Count Georg von Hertling (1843-1919) on 3 October 1918. The idea was to signal to American President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) that a reformer had been appointed. However, this backfired when a private letter Baden had written in January 1918 was published. The letter showed that he had previously opposed democratic reforms and a negotiated peace.

From the beginning of his short Chancellorship Baden was never the initiator, but driven by events. During the first half of October Erich Ludendorff demanded Baden should do everything possible to obtain an immediate armistice. Max of Baden had not been aware of the seriousness of the military situation but eventually yielded. During the diplomatic exchange of notes between the German and American governments Baden continued to make concessions, ending the submarine warfare, and changing the German constitution into a parliamentary system. He even forced the Kaiser to dismiss Ludendorff after the OHL attempted to sabotage his reforms and abandon the diplomatic search for peace. The reforms he initiated went entirely against his inner political convictions. In a letter to Houston Stewart Chamberlain (1855-1927) a few years before he had stressed that the “western” model of parliamentarianism could not work in Germany.

Max of Baden also had to change his monarchical beliefs. He had promised to help keep Wilhelm II on his throne, but by 31 October even he accepted that this was impracticable. Though Baden originally wanted to save the monarchy, he did not go through with a plan discussed with Friedrich Ebert (1871-1925). It would have meant making Ebert Chancellor and allowing Baden to stay on as Regent for Wilhelm’s grandson. However, the Kaiser refused to abdicate. The pressure led Baden to suffer a nervous breakdown. Nevertheless, he recovered sufficiently and on 9 November, when the revolution that had spread across Germany during the previous week finally arrived in Berlin, Baden unilaterally announced the abdication of Wilhelm II and Wilhelm, Crown Prince of Germany (1882-1951). Afterwards, Baden fled the scene and Germany was declared a republic.

Max of Baden’s chancellorship had only lasted for five weeks. He retreated to Castle Salem where in 1920 he founded an elite boarding school with Kurt Hahn. During the Weimar Republic he was ostracized by the majority of his peer group. Ex-Emperor Wilhelm II never forgave Baden for “his betrayal”, claiming that if he returned to the throne, Baden would have to leave the country immediately or hang, since “a bullet was too good for that man.”[4] Baden died of natural courses in 1929, only a year after he had become the head of the House of Baden.

Karina Urbach, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton

Section Editor: Mark Jones

Notes

- ↑ Machtan, Lothar: Prinz Max von Baden. Der letzte Kanzler des Kaisers, Berlin 2013, pp. 154ff.

- ↑ Urbach, Karina: Go-Betweens for Hitler, Oxford 2015, pp. 103ff.

- ↑ Urbach, Karina/Buchner, Bernd: Houston Stewart Chamberlain und Prinz Max von Baden, in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 1 (2004), pp. 121–177.

- ↑ Quoted in ibid., p. 107.

Selected Bibliography

- Geyer, Michael: Insurrectionary warfare. The German debate about a levee en masse in October 1918, in: Journal of Modern History 73/3, 2001, pp. 459-527.

- Machtan, Lothar: Prinz Max von Baden. Der letzte Kanzler des Kaisers, Berlin 2013: Suhrkamp.

- Maximilian, Prince of Baden: Erinnerungen und Dokumente, Stuttgart 1927: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt.

- Maximilian, Prince of Baden, Mann, Golo / Burckhardt, Andreas (eds.): Erinnerungen und Dokumente, Stuttgart 1968: E. Klett.

- Urbach, Karina: Go-betweens for Hitler, Oxford 2015: Oxford University Press.

- Urbach, Karina; Buchner, Bernd: Prinz Max von Baden und Houston Stewart Chamberlain. Aus dem Briefwechsel 1909-1919, in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 52/1, 2004, pp. 121-177.