Introduction↑

The general strike represented the pinnacle of the intense social conflicts that shook Switzerland, like other European countries, at the end of World War I. In the war years, a deep rift opened between a portion of the businesspeople and farmers, on the one side, and workers on the other side. While some businesspeople made enormous war profits and farmers enjoyed an economic boom the likes of which they had not known in a long time, workers experienced increasing poverty. However, they did not fail to notice the economic importance they had gained in wartime. The army’s mobilization and the bourgeoning economy in certain sectors ensured favourable labour market conditions. This meant that strikes, which sharply increased in frequency from 1917, had greater prospects of success.

| Year | Strikes | Strikers | Working Days Lost |

| 1911 | 143 | 17,784 | 329,323 |

| 1912 | 114 | 10,607 | 371,504 |

| 1913 | 92 | 10,012 | 263,668 |

| 1914 | 47 | 5,418 | 272,296 |

| 1915 | 12 | 1,547 | 29,521 |

| 1916 | 35 | 3,330 | 32,597 |

| 1917 | 140 | 13,459 | 158,654 |

| 1918 | 268 | 24,382 | 289,860 |

| 1919 | 237 | 22,137 | 337,801 |

| 1920 | 184 | 20,103 | 512,129 |

| 1921 | 55 | 3,705 | 140,228 |

Table 1: Strikes 1911-1921 [1]

Endowed with extraordinary powers due to the war, public authorities only reacted late and, overall, very little to concerns put forth by the labour organisations. Therefore, for labour organisations it made sense to consider strike as a means to apply political pressure. The Oltener Aktionskomitee (OAK) repeatedly sent the federal government demands underpinned with strike threats. In contrast to the early war years, the federal government now had to respond at least in part to working-class issues.

In autumn 1918, the collapse of the old order and rise of the labour movement in Germany and Austria were impossible to ignore and right-wing circles increasingly feared a similar development in Switzerland. Some saw the strike of Zurich bank employees (from 30 September/1 October 1918), which the radical Zurich workers’ union supported with a local general strike, as a rehearsal for the revolution. Others – like General Ulrich Wille (1848-1925) – wanted to teach the protesting workers a lesson, if possible before the foreseeable demobilisation of the army. Troops demonstratively marched into Zurich on 7 November.

The Protest Strike↑

At its 20th meeting on 6 November, the OAK had yet no idea about the forthcoming events and dealt with routine business. It met on short notice for a special meeting on 7 November given the general outrage that the deployment of troops had caused among organised labour. After extensive debates and aiming to keep hold of events and channel the protest movement, it called for a work stoppage in 19 industrial centres.

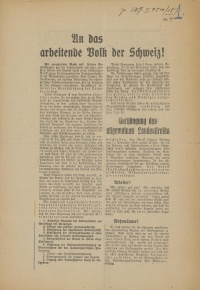

The protest strike of 9 November, the Saturday which saw the collapse of the German Empire, ran without incidents. In Zurich, the workers’ union decided to continue the movement until the state of siege was lifted. On Sunday, 10 November, demonstrators and the military clashed violently on Münsterplatz, which fuelled the conflict. The OAK was faced with a choice between associating itself with the Zurich approach or the loss of its influence. Ultimately, it called for an unlimited general strike for Tuesday, 12 November. The proclamation included nine demands: 1. Immediate re-election of the national council on the basis of proportional representation; 2. Active and passive women’s suffrage; 3. The introduction of a general obligation to work; 4. The introduction of the 48-hour week; 5. Army reform; 6. The securing of food supplies; 7. The establishment of old age and disability insurance; 8. State monopolies on import and export; and, 9. The payment of public debt by the wealthy.

The National General Strike↑

On 11 November, the day of the Armistice of Compiègne, work resumed in most places; the most important exception was Zurich. The national general strike started on 12 November, a Tuesday. A survey by the Swiss Federation of Trade Unions (Schweizerischer Gewerkschaftsbund, SGB) recorded 250,000 strikers. The deepest impression was made by the participation of railway workers, which carried the movement into rural areas that were otherwise hardly affected by the strike. The call to strike was received with hesitation in many places in the French and Italian-speaking parts of Switzerland. In general, the strike was peaceful; in their strongholds the labour organisations had been able to push through a disciplined approach which included alcohol bans. The situation only briefly got out of control in a few places, usually after provocative military deployments. The worst was in Grenchen, where three strikers died under military fire on 14 November.

The federal government – aided by its extraordinary powers – had already subordinated federal employees with a military order on November 11. While at first the federal government and various cantonal governments had shown a willingness to make concessions, their position increasingly hardened. On the one hand, they saw that they had overestimated the danger; on the other, the uncompromising section of the right-wing camp rapidly gained ground, especially in the federal assembly convened on 12 November. In addition, with the help of senior staff, students and newly formed militias, it was possible to maintain important services. Strengthened in such a way, the federal government demanded an unconditional end to the strike on 13 November. The OAK, which feared military repression, complied with the ultimatum in the early morning of 14 November. On 15 November, a Friday, work was resumed nearly everywhere.

Consequences↑

The general strike led to short and long-term consequences on the broad spectrum between repression and reform. Some of the labour force suffered disadvantages at work, especially wage deductions. As there were no offences against criminal law, the legal persecution was transferred to the military justice system. Charges were brought against over 3,500 people, especially railway workers. These led to 147 convictions for breaking the previously mentioned military order of the 11 November. In the main trial, which took place from 12 March to 9 April 1919, a military court convicted Robert Grimm (1881-1958), Friedrich Schneider (1886-1966) and Fritz Platten (1883-1942) from the OAK of mutiny. They were each sentenced to six months’ jail. The editor of the Zurich party organ Volksrecht, Ernst Nobs (1886-1957), was sentenced to four weeks’ jail for breaking the military order of 11 November. The reform section of the Free Democratic Party no longer played a role in the right-wing block. The newly-formed militias, especially the Schweizerischer Vaterländischer Verband (SVV), which was founded in 1919, consolidated their structures. Viewed as an attempt to launch a revolution, the strike was used for decades thereafter to stigmatise the left. Research which by and large exonerated the strike leaders, especially the works of Willi Gautschi (1920-2004), became only widely known after the 50th anniversary of the strike in 1968.

For a long time and aided by a similarly critical perception on the left (the strike as a failure), the negative interpretation obscured the general strike’s achievements. The most direct tangible result was a rapid, massive shortening of working hours in 1919 (48-hour week). In addition, industrial relations changed fundamentally. The export industry, which had formerly hardly negotiated with unions, was now prepared to reach broad accords but not yet collective agreements. Federal authorities increasingly included union representatives in decision-making processes. And it was not least because of the experience of the general strike that labour organisations were included in the war economy in World War II, the problem of distribution given a high priority, collective agreements shaken on before the end of the war, and preparations for path-breaking social policy reforms for the immediate post-war period with the creation of the old age and survivors’ insurance (Alters- und Hinterbliebenenversicherung, AHV) were undertaken.

For the first half of the 20th century scholarship on the strike focused, above all, on the question of whether it was a legitimate movement or an attempted coup. After the first source-based studies by Willi Gautschi showed no evidence for violent aims on the part of the strike leaders, numerous mostly small, regional studies followed, which nearly unanimously documented a peaceful movement.

Bernard Degen, Universität Basel

Section Editor: Roman Rossfeld

Translator: Brier Field

Notes

- ↑ Table created by author.

Selected Bibliography

- Degen, Bernard: Abschied vom Klassenkampf. Die partielle Integration der schweizerischen Gewerkschaftsbewegung zwischen Landesstreik und Weltwirtschaftskrise (1918-1929), Basel 1991: Helbing & Lichtenhahn.

- Degen, Bernard: Theorie und Praxis des Generalstreiks, in: Degen, Bernard / Schäppi, Hans / Zimmermann, Adrian (eds.): Robert Grimm. Marxist, Kämpfer, Politiker, Zurich 2012: Chronos, pp. 51-62.

- Gautschi, Willi: Der Landesstreik 1918, Zurich 1968: Benziger.

- Gautschi, Willi (ed.): Dokumente zum Landesstreik 1918, Zurich; Cologne 1971: Benziger.

- Mazbouri, Malik; Perrenoud, Marc; Vallotton, François et al.: Der Landesstreik 1918. Krisen, Konflikte, Kontroversen, in: Traverse. Zeitschrift für Geschichte / Revue d'histoire 25/2, 2018.

- Oltener Aktionskomitee: Der Landesstreik-Prozess gegen die Mitglieder des Oltener Aktionskomitees vor dem Militärgericht 3 vom 12. März bis 9. April 1919, Bern 1919: Unionsdruckerei.

- Rossfeld, Roman / Koller, Christian / Studer, Brigitte (eds.): Der Landesstreik. Die Schweiz im November 1918, Baden 2018: hier + jetzt.

- Vuilleumier, Marc / Kohler, François / Ballif, Eliane et al. (eds.): La Grève générale de 1918 en Suisse, Geneva 1977: Grounauer.