New Approaches to Spanish Neutrality: “Silent Wars”↑

Despite the relative scarcity of studies on Spain during the Great War, recent research has paid attention to what the country offered to both warring sides as a neutral battlefield. On the one hand, Spain was one of the biggest neutral markets, and enjoyed a key location in sea-trade routes. On the other hand, neutrality posed a challenge to the Spanish government, which constantly had to negotiate between warring external pressures. Works published in commemoration of the outbreak of the war have focused on Spain’s transformation into a front on which the Allies and the Central Powers conducted a secret, harsh war. In particular, Allied intelligence schemes tended to rely on the cooperation of the Dirección General de Seguridad (the Department of Public Safety, under the authority of the Spanish Home Office). Liberal and conservative cabinets in Madrid often interpreted their country’s traditionally friendly relations with France and Great Britain as a sort of “neutral alliance.” However, the unbalanced, pro-Allied view on the secret war carried out in Spain contrasts with a lack of research on the German course of action.[1]

Building Intelligence Networks in Spain↑

Eduardo Dato’s (1856-1921) cabinet proclaimed neutrality in August 1914, but gave the British and French Foreign Offices notice that Spain would exercise “benevolent neutrality” towards the Entente. Despite some previous dissension among Spanish policymakers over the burden of submitting their African and Mediterranean policies to France and Great Britain, when war broke out, colonial ambitions revolved around Tangier and the hope that the French would recognize a Spanish protectorate in Morocco. On 19 August 1914, the Romanonist faction of the Liberal Party published an article in the Diario Universal calling for the abandonment of official neutrality in favour of the Entente Powers, arguing that only be entering the war could Spain achieve its national interests in North Africa. This was the starting point for Germany’s relentless attempts to maintain Spanish neutrality.

Early German Mobilisation against Anglo-French Hegemony↑

When Prince Maximilian von Ratibor und Corvey (1856-1924) was nominated as the new German ambassador to Spain in 1912, he had already expressed his sentiments regarding the need to counteract the powerful Anglo-French influence on the Spanish economy. Despite the leading presence of German capital and engineers in electric and mining companies, it was a small community compared to the French and the British. Ratibor trusted a fellow countryman in Barcelona, August Hofer, with the promotion of a commercial scheme that received almost no financial support of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Berlin.[2] Additionally, Major Arnold Kalle (1873-1952) was appointed military attaché to the Madrid embassy in April 1913.

Despite the modest beginnings of this commercial scheme, the war improved and strengthened the German Foreign Office’s commitment to assisting in the economic fight against the Entente in Spain. Between September and December 1914, a full-on propaganda network spread out around the country, with the cooperation of local branches of companies such as the Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft (AEG). At the same time, Lieutenant Commander Hans von Krohn was appointed to Madrid on a special mission (and later designated as German naval attaché in September 1916). In their work, both Kalle and Krohn succeeded in using their connections with the Spanish elite to exploit the social breach between the church and monarchist parties (identified with the “official Spain”) on the one hand and the left-wing parties and workers (the so-called “real Spain”) on the other. Kalle, for instance, was close to Alfonso XIII, King of Spain's (1886-1941) royal circle.

In October 1914, more than 400 Spanish journalists were invited to work to varying degrees on German propaganda, sponsored by German Foreign Service subsidies for conservative newspapers like La Tribuna.[3] Whereas propagandists gained control of newspapers, the German secret service was committed to hindering the Allies’ access to supplies. Funds available for sabotage plots against Allied industries like the Rio Tinto Company soon increased. The German ambassador, Prince Ratibor, was actively involved in those schemes.

↑

For security reasons, the British established an intelligence centre in Gibraltar in 1903. The rapprochement between Russia and France had caused serious concerns about imperial trade routes. The promotion of national trade was also a driving force behind the quick expansion of the naval network. Gibraltar, where the British had an office devoted to trade intelligence, was well placed for operations in Spain and Morocco. German naval intelligence, for its part, established a commercial service, with the help of the Mannesmann brothers, in Morocco.[4]

In September 1913, when Major Charles Julian Thoroton (1875-1939) of the Royal Marine Light Infantry was serving on the H.M.S. Cormorant, he received a commission to act as an intelligence officer in Gibraltar, sparking a meteoric rise in his career. By 23 September 1915, he had already been promoted to General Staff Officer (G.S.O.) 1st Grade, having been added to the List of War Staff Officers “without undergoing the usual examination”. On 3 October 1916, he was promoted to Brevet Lieutenant Colonel.[5] However, most of the records from his time as the head of the British secret service in Spain were unexpectedly lost in the aftermath of the war. He may very well have destroyed them himself, keeping only “those papers which he thought necessary to defend himself in case of an attack being made on him for some of his more questionable activities” during the war.[6]

The responsibility for gathering naval intelligence initially fell on the most highly-qualified members of the British community all over Spain. Consular officers, thanks to their experience and knowledge of the environment, enjoyed a privileged view of affairs in ports. In fact, British consular officers did a great deal to make their fellow countrymen cease commercial intercourse of any kind with locals suspected of trading with the enemy (confidential blacklists begun to circulate around main ports). In April 1915, the British Consul General in Barcelona, Charles Smith, was even instructed to hire the services of the local detective agency, Tresolls, since the Restriction on Enemy’s Supply Committee in London complained about vague commercial reports.[7] It was not easy for members of the consular service to accept the new operational instructions connected with naval intelligence regarding Spain. Thoroton usually complained about consular indiscretions. The temporary consul in Malaga, Godfrey Edward P. Herstlet, as a result of his excessive wordiness, had made Thoroton’s organization come in full sight of German agents. The head of the organization was himself at Gibraltar. Lieutenant Arthur Blackwood and his assistant Mr. Sullivan were in charge of the north of Spain. They had a yacht at their disposal for surveillance in the Bay of Biscay. In the south and in the Spanish Levante, Lord Abinger, Shelley Leopold Lawrence Scarlett (1872-1917), who served the Admiralty War Staff, ran operations. He counted on assistants in Huelva, Seville, Malaga, Cartagena, Valencia and Barcelona. The south-eastern network also had a yacht for coast surveillance. Navy officers were progressively allocated to consulates. Some of them, like Lieutenant Albert E. Dawson (Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve) in Bilbao, were acting as trade vice consuls.[8] In July 1915, Lieutenant Oliver Baring was appointed to Madrid as a liaison in the three-way transfer of information between the Admiralty War Staff, the consular service and Gibraltar. In January 1916, “New Rules for the Secret Service” came into force. In February, the Admiralty decided to abolish the title of Naval Intelligence Officer “to avoid unnecessary attention”, especially in neutral environments. Intelligence officers were then designated as “General Staff Officers”.[9]

At that time, Lieutenant Wilhelm Canaris (1887-1945) had been sent to support German naval espionage in the Strait of Gibraltar. Together with Albert Hornemann, he organized local networks of seamen and port authorities to pass information on the positions of the Spanish steamers, so German agents spread along the coastline between Cádiz and Granada. However, Canaris was soon unveiled and became an enemy target. Even though he operated from von Krohn’s home in Madrid, he often had to change his address to escape Allied surveillance. In October 1916, Canaris fled away in the U-35. The Spanish police also exerted harsher pressure on German agents. In a report written on 3 October 1916, the famous novelist and British agent A. E. W. Mason (1865-1948) praised the head of the Criminal Investigation Office in Barcelona, Ramón Carbonell, for having observed and prosecuted the German network. The Germans apparently had to transfer a part of their organization from Barcelona to Valencia.[10]

Juan March↑

Thoroton was successful in making Juan March (1880-1962), the famous Spanish smuggler, his collaborator. March’s contraband flotilla, registered at Gibraltar, served as British eyes from Oran and Algiers to the Balearic Islands. In May 1915, John MacNaughten, Thoroton’s man in Valencia, arranged a secret meeting between the contrabandist and the General Staff Officer.[11] Nonetheless, the French particularly distrusted March. They had reported that March was running German reservists across to Italy, as well as supplying submarines in the Balearic Islands. However, the Spaniard acted as a British double agent, since he was in touch with pro-German Spanish authorities and customs officials. In June 1915, stable cooperation with the smuggler was established. Thoroton sent the British ambassador, Arthur Hardinge (1859-1933), confirmation of that alliance:[12] “As you rightly surmise, I intend to keep an eye on Don Juan in spite of our treaty. Treaties are of small value nowadays, though I expect Juan is more to be trusted than any Hun”. On 18 August 1915, the Italian consul in Gibraltar informed Rome that the Spanish seaboard was under Major Thoroton’s surveillance. He went on stating that the British were in liaison with Juan March, who had control of over 240 motor ships and monoplanes.[13]

March’s business partners also assisted the British organization. For instance, José Juan Domine (1869-1931), a liberal member of the Spanish senate and the owner of the Compañía Valenciana de Vapores de África, a shipping company on the British whitelist, actively cooperated with Gibraltar. In 1916, he founded the Transmediterránea Company, which would be working exclusively for the Allies. That year, March and Thoroton met Colonel Goubert in Paris, coinciding with the arrangements for the Allied Economic Conference in June. However, relations between March and the French continued to be strained.

Allied but Rivals against Germany: The French and the Italians Enter into Play↑

The French had gradually concluded that their British allies in Spain were not always working on their shared cause. Anglo-French cooperation in Spanish Morocco certainly proceeded more smoothly than it did on the peninsula. Thoroton was on good terms with the French Resident in Morocco, General Louis Hubert Lyautey (1854-1934). In December 1915, Robert de Roucy (1881-1919) was appointed naval attaché in Madrid. His mission was to promote a secret service modelled on the British one. The military attaché, André Tillion, became head of the Army’s information branch.[14] The French were able to mobilise their own resources relatively quickly. Motivated by either pecuniary interest or true patriotism, members of the greater French community—consuls, business managers, directors of banks and mining companies—started to pass information on the naval organisation. In Barcelona, the French consul general, Fernand Gaussen, led the Allied action in connection with the Naval Office based in Toulon. In the spring of 1916, Albert Mousset (1883-1975), an expert in Spanish history, ran a French propaganda bureau, while the British operated through the Agencia Anglo-Ibérica, directed by John Walter, who was descendant of the founder of the Times.

At the same time, the Italians had designated Lieutenant Commander Filippo Camperio (1873-1945) as naval attaché at the Italian embassy. The Italians, due to their less prominent presence in the country and the limited funds available, had more trouble creating a service. Nonetheless, they built up their organization in the Spanish Levante. As a rule, Thoroton refused to share with Roucy and Camperio either specific information or the general privileges and advantages that his naval organization had in Spain because of early mobilisation.[15] In May 1916, the head of the French Office in Toulon complained sharply about how the British were concealing sources of information in Barcelona from them. For the French, it was clear that the British were playing a “double game” in Spanish intelligence matters. They also kept insisting that the British should appoint a naval attaché to Madrid, which would make communications easier and more direct between Allied services. But the request was not entirely fulfilled until March 1918, when Flag Captain John Harvey arrived in Madrid from Gibraltar (he had been designated naval attaché in December 1917). One of Harvey’s main duties at the British embassy consisted of smoothing over inter-Allied disputes. Even if confidential communications improved in Madrid, rivalries and personal animosities between local heads of service continued until the war ended.

Submarine Warfare↑

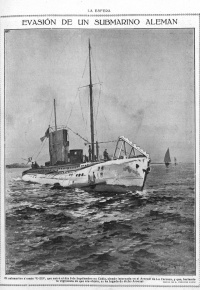

In 1917, apart from growing demands of inter-Allied cooperation, unrestricted submarine warfare in the Mediterranean would severely challenge Allied secret services’ ability to keep the Spanish seaboard under control. The communications between Austrian and German boats anchored in Andalusian harbours and U-boats was a major concern. Flashing lights were seen at night in Cádiz, Malaga and Almeria. They were suspected of being Morse signals for U-boats positioned between 600 metres and one kilometre from the seaboard. Furthermore, two interned German submarines, the UC-52 and the UB-49, fled the San Fernando navy yard in June and October 1917, respectively. Emilio Winter, the German consul in Cádiz, accused of being complicit with the Spanish military port authorities, had to defend himself in the local newspaper Diario de Cádiz.[16] Another example of these “cloak-and-dagger” episodes in the north of Spain was the famous Erri Berro affair, connected with a German wolfram contraband plot.[17]

German submarine manoeuvres also put the convoy system at risk in the Mediterranean. On 10 May 1917, the first convoy had sailed from Gibraltar. The French and British foreign offices put harsh pressure on the Spanish government to prosecute German espionage on the Spanish coasts. Officers of the Dirección General de Seguridad were accordingly deployed at strategic seaports. The French, on their own, took advantage of the excavations at the archaeological site of Baelo Claudia (Cádiz) to gather information on enemy moves in the Strait. Deported Germans from Cameroon, who had been interned in small coastal towns like Puerto de Santa María and Zahara de los Atunes, were also under strict surveillance in the region. They had been seen taking pictures of railways and goods to be shipped from the ports of Cádiz and Algeciras.

“Between War and Revolution”↑

In the summer of 1917, military, political and social conflicts broke out in Spain simultaneously. The military movement (Juntas Nacionales de Defensa) against the privileges of the Moroccan section of the Spanish army, the challenge in Barcelona to the parliament in Madrid (Asamblea de Parlamentarios) and the revolutionary general strike had serious effects on intelligence operations. Despite Alfonso XIII’s contradictory sentiments regarding belligerent sides as military operations evolved, he started to hold a stronger Germanophile position. The king was ever more scared of the “red peril.” In August 1917, Lieutenant Commander Aristide Bergasse du Petit-Thouars (1872-1932) replaced Roucy as head of the French secret service. A Spanish Freemason plot came to light and the French secret service had apparently been engaged in the Masons’ republican activities.[18]

Social instability also coincided with the expansion of counterespionage on a grand scale. On 22 May 1916, the British War Office had already appointed a military control officer (MCO) in Madrid to supervise travel visas issued to the United Kingdom. Strong evidence was also found in Barcelona that passports had been issued to travellers who should have been denied for security reasons. The MCO’s task was to prevent German agents from fleeing Spain. Apart from monitoring the issue of visas in their consulates, the Allies had to watch out for movement of people across the Franco-Spanish border in Irun (Basque country); the Anglo-Spanish frontier in Algeciras (Cádiz-Gibraltar); and the Spanish-Portuguese border in Ayamonte (Guadiana River, Huelva).

However, the most serious challenge came from social unrest. A wave of industrial strikes posed a threat to Allied supplies of pyrites and oxides in late 1917. A memorandum circulated by the British Ministry of Munitions highlighted how vital Spanish raw materials were for the Allied war effort:[19]

The critical situation required the Allies to cooperate more with Spanish authorities. There was a shared interest in fighting subversives who were disturbing public order. But also, the close cooperation of the Spanish police chief in Barcelona, Manuel Bravo Portillo (1876-1919), with the German naval espionage showed the extent to which the bribery and corruption pervaded the Spanish administration. While Gibraltar officers infiltrated workers’ rallies and strikes, the Dirección General de Seguridad identified possible German instigators. The French sought to distance themselves from the British in the labour question posed in the south of Spain. The battle against German influence on the workers’ movement had to be fought in the field of propaganda, too.[20] In the summer of 1918, the French network focused on the foundation of the Federación Regional Obrera (Regional Workers Federation). In December that year, 21,500 workers had supposedly joined the new organization.

Conclusion↑

In a war of attrition, the need to control Spanish sea trade (raw materials exports), heavily dependent on Great Britain and France, explains the key role that maritime espionage initially played. However, the inequality between sides was soon apparent, not only against the background of Spanish relations with the Entente prior to the war, but also on the ground, where the imbalance was even greater. Spain decided to apply “benevolent neutrality” towards the Allied side, and thanks to their bases at Gibraltar and Toulon, the Anglo-French services enjoyed a strategic advantage. However, German propaganda and espionage activities could still be more extensively studied, going far beyond notorious particular cases.

The conclusion drawn here ties in with the revision of Spanish neutrality between 1914 and 1918. Neutral Spain became a theatre of a silent war, in which the Entente and the Central Powers fought each other relentlessly. Their soldiers were intelligence agents who tried to make Spaniards work for their own cause by either force or persuasion. Antonio Maura’s provisions of “the indispensable power to guarantee Spain’s neutrality” (9 July 1918), so-called “Law against Espionage”, even as a subterfuge to impose press censorship, indicates the extent to which warring interference had internally destabilized the country since the beginning of the war.

Carolina García Sanz, University of Seville

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Notes

- ↑ Javier Ponce’s and Anne Rosenbusch’s contributions on German naval warfare and Espionage respectively represent an exception. See, for instance: Ponce, Javier: Neutrality and submarine warfare. Germany and Spain during the First World War, in: War and Society 24/4 (2015), pp. 287-300; Rosenbush, Anne: Guerra Total en territorio neutral: Actividades alemanas en España durante la Primera Guerra Mundial, in: Hispania Nova, 15 (2017) pp. 350-372. Also, on German plots interfering with Spanish politics in 1917, see: González Calleja, Eduardo / Aubert, Paul: Nidos de espías. España, Francia y la Primera Guerra Mundial 1914-1918, Madrid 2014, pp. 283-290.

- ↑ Carden, Ron: German Policy toward Neutral Spain, 1914-1918, New York 1987, pp. 56-91.

- ↑ Delaunay, Jean Marc: Des palais en Espagne. L'Ecole des hautes études hispaniques et la Casa de Velázquez au cœur des relations franco-espagnoles du XXe siècle (1898-1979), Madrid 1994, p. 91.

- ↑ Vickers, Philip: Finding Thoroton. The Royal Marine who ran British Naval intelligence in the Western Mediterranean in World War One, London 2013, p. 14.

- ↑ Vickers, Philip: Finding Thoroton, p.72.

- ↑ Beesly, Patrick: Room 40. British Naval Intelligence 1914-1918, Oxford 1984, pp. 190-191.

- ↑ The National Archives (TNA), Foreign Office 382/388, Smith to Grey, 24 Apr.1915 nº106.

- ↑ García Sanz, Carolina: La Primera Guerra Mundial en el Estrecho de Gibraltar. Economía, Política y Relaciones Internacionales, Madrid 2011, pp. 199-285.

- ↑ TNA, Colonial Office 323/705 Confidential 1 Feb. 1916.

- ↑ Vickers, Philip: Finding Thoroton, pp. 100-101.

- ↑ Vickers, Philip: Finding Thoroton, p. 142.

- ↑ García Sanz, Carolina: La Primera Guerra Mundial en el Estrecho de Gibraltar, pp. 239-240.

- ↑ Archivio del Ministero degli Affari Esteri Rome (AMAER), busta 80.

- ↑ García Sanz, Fernando: España en la Gran Guerra. Espías, diplomáticos y traficantes, Madrid, 2014, pp.64-89.

- ↑ García Sanz, Carolina: Primera Guerra Mundial, pp. 261-277.

- ↑ García Sanz, Carolina: Primera Guerra Mundial, p.182.

- ↑ Beesly, Patrick: Room 40, pp. 190-191; Andrew, Christopher: The Making of the British Intelligence Community, London, 1985, pp. 115-119.

- ↑ García Sanz, Fernando: España en la Gran Guerra, pp. 76; 269-270.

- ↑ TNA, Munitions 4/2193.

- ↑ García Sanz, Carolina: Primera Guerra Mundial, pp. 196-198.

Selected Bibliography

- Andrew, Christopher M.: Secret service. The making of the British intelligence community, London 1985: Heinemann.

- Aubert, Paul: La propagande étrangère en Espagne dans le premier tiers du XXe siècle, in: Mélanges de la Casa de Velázquez 31/3, 1995, pp. 103-176.

- Beesly, Patrick: Room 40. British naval intelligence, 1914-1918, Oxford; New York 1984: Oxford University Press.

- Calvo-Sotelo, Mercedes Cabrera: Juan March (1880-1962) (1 ed.), Madrid 2011: Marcial Pons Ediciones de Historia.

- Carden, Ron M.: German policy toward neutral Spain, 1914-1918, New York 1987: Garland Publishing.

- Delaunay, Jean-Marc: Des palais en Espagne. L'École des hautes études hispaniques et la Casa de Velázquez au coeur des relations franco-espagnoles du XXe siècle, 1898-1979, Madrid 1994: Casa de Velázquez.

- García Sanz, Carolina: La Primera Guerra Mundial en el Estrecho de Gibraltar. Economía, política y relaciones internacionales, Madrid 2011: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas.

- García Sanz, Carolina / Fuentes Codera, Maximiliano: Toward new approaches to neutrality in the First World War. Rethinking the Spanish case-study, in: Ruiz Sánchez, José-Leonardo / Cordero Olivero, Inmaculada / García Sanz, Carolina (eds.): Shaping neutrality throughout the First World War, Seville 2016: Editorial Universidad de Sevilla, pp. 39-62.

- García Sanz, Fernando: España en la Gran Guerra. Espías, diplomáticos y traficantes, Barcelona 2014: Galaxia Gutenberg.

- González Calleja, Eduardo / Aubert, Paul: Nidos de espías. España, Francia y la Primera Guerra Mundial, 1914-1919, Madrid 2014: Alianza.

- Jeffery, Keith: MI6. The history of the Secret Intelligence Service 1909-1949, London 2010: Bloomsbury.

- Mueller, Michael: Canaris. Hitlers Abwehrchef, Berlin 2006: Propyläen.

- Ponce, Javier: Neutrality and submarine warfare. Germany and Spain during the First World War, in: War and Society 34/4, 2015, pp. 287-300.

- Rosenbusch, Anne: Guerra Total en territorio neutral. Actividades alemanas en España durante la Primera Guerra Mundial, in: Hispania Nova 15, 2017, pp. 350-372.

- Vickers, Philip: Finding Thoroton. The royal marine who ran British naval intelligence in the western Mediterranean in World War One, Southsea 2013: Royal Marines Historical Society.