Introduction↑

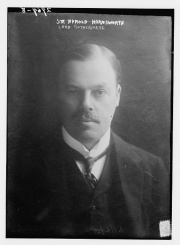

Harold Harmsworth (1868-1940), ennobled in 1914 as Lord Rothermere, was one of Britain’s leading newspaper proprietors and businessmen. As the brother and political ally of Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe (1865-1922), he was associated with the destabilisation of the Asquith administration in 1915-16, and was appointed as Air Minister by David Lloyd George (1863-1945) in 1917. Although his public interventions were not as high profile as some other “press barons” in this period, his wartime experiences would shape his world-view with significant consequences for interwar British politics.

Rothermere was born in 1868, the second son of an English barrister, Alfred Harmsworth, and his Irish wife, Geraldine Mary Harmsworth. He was educated at Marylebone Grammar school, before working in a clerical role at the Board of Trade. His fortune was made, however, by joining his brother Alfred’s burgeoning publishing business. He lacked Alfred’s brilliance as a journalist and entrepreneur, but possessed considerable talents in finance and administration. As a partnership, they created the most successful newspaper and magazine business of the era, with a host of a popular periodicals supplementing their market-leading newspapers, the Daily Mail (1896) and the Daily Mirror (1903). Rothermere eventually became a newspaper proprietor in his own right, acquiring the Glasgow Record and Mail in 1910, taking over the Daily Mirror from Northcliffe in 1914, and founding the Sunday Pictorial in 1915.

Wartime roles↑

Newspaper Owner↑

Rothermere’s Daily Mirror, a “picture paper” which had pioneered the integration of photographs into the pages of the daily press, achieved great commercial success during the war due to the considerable public appetite for its images. The paper did not have a particularly distinctive editorial line, generally following in the footsteps of Northcliffe’s Daily Mail in its criticism of Herbert Henry Asquith’s (1852-1928) leadership, and swinging behind Lloyd George after 1916. Nevertheless, its photographic features provided a popular, if heavily restricted, visual record of the war. Spotting a gap in the market for a Sunday picture paper, Rothermere launched the Sunday Pictorial on 14 March 1915, and found instant success, with early issues selling well over 1 million copies. The paper featured a broad range of contributors, including the author Arnold Bennett (1867-1931), but its greatest impact was probably created by providing a regular platform for the demagoguery of Horatio Bottomley (1860-1933), lambasting the evils of the “Germhuns”. In the process, the Pictorial contributed to the consolidation of a rather vicious form of popular anti-Germanism.

Official positions↑

Rothermere’s administrative abilities were put to use in 1916 when he was appointed to the Director-Generalship of the Royal Army Clothing Department. While less directly involved than Northcliffe and Max Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook (1879-1964) in the intrigues that led to the fall of Asquith in December 1916, he was nevertheless viewed by critics as an overmighty “press baron” seeking to exert influence behind the scenes. Such suspicions were consolidated by his appointment as Air Minister in November 1917. Rothermere’s brief was to amalgamate the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service into a single unit – the Royal Air Force – which was duly achieved in April 1918. Nevertheless, his tenure was a brief and unhappy one, plagued by tensions with his Chief of Air Staff, Sir Hugh Trenchard (1873-1956), who eventually resigned, and then rocked by the death in February 1918, of his eldest son Vyvyan Harmsworth (1894-1918), only three months after his second son, Vere Harmsworth (1895–1918), had also been killed in action. Crippled by grief and ill-health, Rothermere resigned, his main task completed. He was, however, to retain an interest in the Air Force until his death.

Political Legacies↑

Rothermere’s interpretation of the war and its repercussions had a significant impact on interwar politics. He detested the Communist regime established in Russia after 1917, and thus encouraged the Daily Mail to espouse a vehement anti-socialism once he took over ownership on Northcliffe’s death in 1922. The high point of this “red scare” came shortly before the 1924 general election, when the Mail’s published the forged “Zinoviev letter”. This letter was purported to be from Comintern chief Grigory Zinoviev (1883-1936) to the Communist Party of Great Britain, offering financial backing for revolutionary activity; this was a blatant attempt to tar the British left with the extremist brush. Rothermere’s increasing disillusionment with British parliamentary democracy led him to herald Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) as “The Leader Who Saved Italy’s Soul” in May 1927. In 1934, Rothermere declared “Hurrah for the Blackshirts” and called on the British public to support Oswald Mosley’s (1896-1980) British Union of Fascists (BUF), describing Italy and Germany as “beyond all doubt the best-governed nations in Europe today”.[1] While open propagandizing for the BUF lasted only six months before differences of opinion forced a split, Rothermere and the Mail did little to conceal their continued approval of Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) and Mussolini’s domestic policies, and in the late 1930s Rothermere continued a fawning correspondence with the Führer, while firmly supporting Neville Chamberlain’s (1869-1940) policy of appeasement.

At the same time, Rothermere believed that Britain needed to negotiate internationally from a position of strength, and, given his earlier experience, he was particularly concerned by the nation’s air capability. In March 1934 he commissioned the Bristol Aeroplane Company to develop a modern, high-specification monoplane; christened the “Britain First”, it was presented to the Royal Air Force in 1935, and eventually became the Blenheim bomber. Rothermere also spent £5,000 establishing and publicising, from 1935, a National League of Airmen, to encourage “a rapid advancement in our Air Force strength”.[2] Rothermere lived just long enough to see Europe slip into another war, in which Britain’s airpower would play a vital role. He died in Bermuda in November 1940, shortly after the Royal Air Force had managed to repel sustained German attacks in the “Battle of Britain”.

Adrian Bingham, University of Sheffield

Section Editor: Jennifer Wellington

Notes

Selected Bibliography

- Bingham, Adrian: Gender, modernity, and the popular press in inter-war Britain, Oxford; New York 2004: Clarendon; Oxford University Press.

- Boyce, D. George: Harmsworth, Harold Sidney, first viscount Rothermere (1868-1940), in: Matthew, H. C. G. / Harrison, Brian Howard (eds.): Oxford dictionary of national biography, volume 25, Oxford; New York 2004: Oxford University Press.

- Koss, Stephen Edward: The rise and fall of the political press in Britain. The twentieth century, volume 2, Chapel Hill; London 1984: The University of North Carolina Press.

- McEwen, J. M.: The national press during the First World War. Ownership and circulation, in: Journal of Contemporary History 17/3, 1982, pp. 459-486.

- Taylor, S. J.: The great outsiders. Northcliffe, Rothermere, and the Daily Mail, London 1996: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.