Prewar Impressions of Germany and of Wilson↑

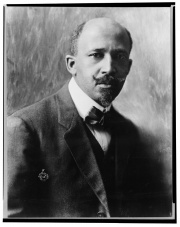

Born after the American Civil War and raised in Massachusetts, William Edward Burghardt Du Bois’s (1868-1963) intellectual talents shone from an early age. Neighbors’ financial support made it possible for him to attend the historically black Fisk University in Tennessee in the 1880s. Experiencing more virulent racism there than he had in Massachusetts, Du Bois earned a bachelor’s degree from Fisk before attending Harvard University for a second bachelor’s. He continued his studies at the University of Berlin and then returned to Harvard, where in 1895 he became the first African American to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard.

Postgraduate study at the University of Berlin in the 1890s gave Du Bois an appreciation of German culture and society, but he noted that a “military spirit...not...confined to the army, but largely...permeate[d] society” and identified anti-Semitic political undercurrents in the Second Reich (1871-1918).[1] He was also somewhat disappointed with the seeming laxity of German socialism.

Du Bois remained fervently committed to integration and to the expansion of political rights to minorities. In 1909, he helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and he edited the organization’s journal The Crisis until 1933. Devoted to civil rights, Du Bois believed they could best be pursued through the education and empowerment of the “talented tenth,” a meritorious segment of each racial and ethnic population.

Du Bois was disappointed in the 1912 Democrat candidate, Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924), whom he had supported during the election. After becoming President, Wilson quickly forgot his own campaign rhetoric about African American uplift and instead allowed federal agencies to re-segregate their offices and dismiss African American civil servants.[2]

Du Bois’s distaste for colonialism shaped his interpretation of the First World War and his view of the war’s significance. He concluded in 1914 that the forces which had actually propelled the outbreak of the European war lay “in a very real sense” with “colonial aggrandizement” in Africa, which several European powers had just finished dividing among themselves.[3] A year later, he had begun to move toward a Marxist interpretation of contemporary events.[4] By 1916, Du Bois determined that the most expansive colonial power, the British Empire, was also “the best administrator of colored peoples” amongst the Europeans. Nonetheless, Du Bois eagerly anticipated the war transforming the global economic and political landscape to empower the colonized people in Africa, as well the peoples of China, India, and those of African descent in the United States.[5]

Supporting War and Voicing Dissent↑

Du Bois’s hope for a new world order prompted him to support the U.S. entry into the conflict in April 1917. The death of rival Booker T. Washington (1856-1915) in December 1915 and the growing popularity of the NAACP journal The Crisis did much to consolidate Du Bois’s position as the principle leader of the African American civil rights movement.[6]

Active participation in combat by African American soldiers seemed a likely way to gain leverage for reshaping post-war American society, but several factors obstructed this. One was the continuing segregation of the U.S. Armed Forces. Another profound problem was the lack of African American officers. To Du Bois’s dismay, the senior African American officer, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Young (1864-1922), was cashiered on a spurious claim of poor health, and the War Department hastened to declare that they would not commission any nonwhite service personnel higher than a captain. Furthermore, the Army preferred to select officers from the ranks of the Regular Army, whose officer corps was almost universally white. This marginalized the effectiveness of Camp Des Moines, the only African American officer training school, and stymied Du Bois’s efforts to create more black officers. Additionally, the military hierarchy placed most African American officers who made it overseas in labor units, redubbed Service of Supply units.[7]

Race Riots and the Silent Parade↑

Race riots flared in many parts of the United States during the war era. Economic fears fed on political and racial tension, sparking race riots in East St. Louis, Illinois in May and July 1917. The violence led to the deaths of as many as 125 people, while 6,000 residents were made homeless. Du Bois rushed to the city to report on the situation for The Crisis. Four weeks after the riot, Du Bois was a key participant in the Silent Parade, the first nonviolent mass demonstration held in New York City. 10,000 marchers, men wearing black and women and children wearing white, marched down Fifth Avenue as a muffled drum roll provided a calculated intensity to the demonstration. Banners called on Wilson to “make America safe for democracy,” applying Wilson’s earlier call to arms for U.S. participation in the war to the home front. The September issue of The Crisis contained a twenty‑four page report with photographs and interviews with victims conducted by Du Bois and social worker Martha Gruening.[8] The East St. Louis Riot was not the only racist‑motivated violence in the post-war period. In the summer and fall of 1919 riots hit Charleston, South Carolina; Washington, D.C.; Knoxville, Tennessee; and Omaha, Nebraska. Chicago also endured a twelve‑day battle. Du Bois urged NAACP members that “when the armed lynchers gather, we too must be armed.”[9] Given the circumstances, he believed that civil rights progress required a capacity for self-defense even as his larger political agenda emphasized peaceful change.

War and Aftermath↑

Du Bois predicted that only an extension of democratic freedom “to the yellow, brown, and black peoples” would avert a racially oriented world war dwarfing the First World War and therefore decried events that moved away from extending democracy. Shortly after the U.S. entered the war, federal agents attempted to intimidate the NAACP newspapers.[10] A year later, in July 1918, Du Bois published an editorial called “Close Ranks,” which called on African Americans to support the war effort. Some scholars and contemporary rivals have perceived this as evidence that Du Bois had opted to accommodate racism, a charge he had earlier leveled at Booker T. Washington.[11] Du Bois’s communication with the Military Intelligence Board reflected his hope to be commissioned as a major in the U.S. Army, which he sought in order to enhance his stature as a civil rights leader.[12] Predictably, officials working in a segregated environment dismissed the notion of providing Du Bois with leverage or influence.

Du Bois also considered writing a three‑volume history of the First World War and its implications for racial transformation.[13] He attended the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, simultaneously convening a Pan-African Congress in Paris with hopes of facilitating self‑determination for colonized peoples and empowering African Americans. This endeavor, undercut by U.S. refusal to issue passports to several would-be participants, had at best a marginal impact on the Paris Peace Conference, prompting Du Bois’s frustration with the limited progress made by earlier moderation. The Pan-African Congress also coincided with a wider adoption of Pan‑Africanism by Du Bois and other civil rights advocates following the war.[14] Du Bois nonetheless remained at odds with black militants such as Marcus Garvey (1887-1940), who rejected the NAACP’s integrationist agenda. It would take another world war, and several decades of escalating racial violence before Du Bois left the United States to live out his final days in the newly-independent Ghana.

Nicholas Michael Sambaluk, United States Military Academy

Section Editor: Lon Strauss

Notes

- ↑ Du Bois, W.E.B.: The Present Condition in German Politics (1893), in: Central European History 31.3. (1998), p. 171; Barkin, Kenneth: W.E.B. Du Bois’ Love Affair with Imperial Germany, in: German Studies Review 28.2 (2005), p. 289-90.

- ↑ Du Bois, W.E.B.: My Impressions of Woodrow Wilson, in: The Journal of Negro History 58.4 (1973), p. 454; Lewis, David Levering: W.E.B. Du Bois, A Biography, New York 2009, p. 332.

- ↑ Horne, Gerald: W.E.B. Du Bois. A Biography, Santa Barbara 2010, p. 74.

- ↑ Marable, Manning: W.E.B. Du Bois. Black Radical Democrat, Boston 1986, p. 94.

- ↑ Lewis, W.E.B. Du Bois 2009, p. 336; Horne, W.E.B. Du Bois 2010, p. 74.

- ↑ Lewis, W.E.B. Du Bois 2009, pp. 335, 344; Rudwick, Elliott M.: W.E.B. Du Bois. Propagandist of the Negro Protest, Atheneum 1968, p. 184.

- ↑ Lewis, W.E.B. Du Bois 2009, pp. 349, 355.

- ↑ Lewis, W.E.B. Du Bois 2009, pp. 349-53.

- ↑ Horne, W.E.B. Du Bois 2010, p. 86.

- ↑ Lewis, W.E.B. Du Bois 2009, p. 359.

- ↑ Rudwick, W.E.B. Du Bois 1968, pp. 200-1; Ellis, Mark: W.E.B. Du Bois and the Formation of Black Opinion in World War I. A Commentary on ‘The Damnable Dilemma,’ in: The Journal of American History 81.4 (1995), pp. 1584-88, 1590.

- ↑ Lewis, W.E.B. Du Bois 2009, pp. 362-3.

- ↑ Lewis, W.E.B. Du Bois 2009, pp. 367-8.

- ↑ Contee, Clarence G.: Du Bois, the NAACP, and the Pan-African Congress of 1919, in: The Journal of Negro History 57.1 (1972), p. 13; Marable, W.E.B. Du Bois 1986, pp. 100-3; Rudwick, W.E.B. DuBois 1968, p. 212.

Selected Bibliography

- Barkin, Kenneth: W. E. B. Du Bois' love affair with imperial Germany, in: German Studies Review 28/2, 2005, pp. 285-302.

- Contee, Clarence G.: Du Bois, the NAACP, and the Pan-African Congress of 1919, in: The Journal of Negro History 57/1, 1972, pp. 13-28.

- Du Bois, W. E. B.: My impressions of Woodrow Wilson, in: The Journal of Negro History 58/4, 1973, pp. 453-459.

- Ellis, Mark: W. E. B. Du Bois and the formation of Black opinion in World War I. A commentary on 'the damnable dilemma', in: The Journal of American History 81/4, 1995, pp. 1584-1590, doi:10.2307/2081650.

- Lewis, David L.: W. E. B. Du Bois, New York 1993: Henry Holt & Co.

- Marable, Manning: W. E. B. Du Bois. Black radical democrat, Boulder 2005: Paradigm Publishers.

- Rudwick, Elliott M.: W. E. B. Du Bois. Propagandist of the Negro protest, New York 1986: Atheneum.