The early years – Military education and first major duties↑

Constantine I, King of Greece (1868-1923) was King of Greece from 1913 to 1917 and from 1920 to 1922. He was the son of George I, King of the Hellenes (1845-1913), and Olga, Queen, consort of George I, King of the Hellenes (1851-1926), from the Russian house of Romanov. After graduating from the Officers’ School of Athens in 1886, he continued his military education in the Berlin Military Academy. This spell in Berlin is thought to have greatly contributed to the formation of the future king’s pro-German attitude, which was further enhanced by his marriage to Sophia of Prussia (1870-1932), sister of Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941). In 1897 Constantine took part in the Greco-Turkish War, serving at the time as head of the troops in the region of Thessaly. His opponents blamed the king for the disastrous end of that campaign; this did not stop him, however, from becoming Chief General of the Greek army in the first decade of the 20th century. In 1909, after a military coup, Constantine was released from his duties – only to be reinstated some time later due to the initiative of the new Prime Minister, Eleutherios Venizelos (1864-1936). From his new position as General Inspector of the Army, Constantine contributed significantly to the good preparation of the armed forces for the upcoming Balkan Wars (1912-13), which proved victorious for Greece. In 1913, in the middle of the First Balkan War, Constantine succeeded his father King George I. The military exploits of the new king, combined with the appeal created by his name – the same as the last emperors of Byzantium – turned him into a living legend for an important part of the population, who regarded him as the person destined to revive the old glory of the Greek nation.

First World War – The disagreement with Prime Minister Venizelos and the “schism” of the Greek state↑

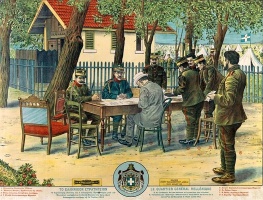

At the time of the outbreak of the First World War, King Constantine disagreed with Prime Minister Venizelos over the role Greece should play in the war. Constantine favored neutrality, while Venizelos claimed that the only real choice for Greece would have been entering the war on the side of the Entente allies, on the basis of the treaty that had been signed with Serbia in 1913. The disagreement over sending Greek troops to stand by the side of the Entente allies led Venizelos to resign twice, in both March and October 1915. The landing of the Allies’ army in Thessaloniki on 5 October 1915 was realized after a secret agreement between the Entente’s governments – especially France – and Venizelos. This agreement, entirely against the will of the King, resulted in the second resignation of the Greek Prime Minister that same day. From that moment on and until June 1917, Greece was ruled by pro-royalist governments whose relations with the Allies were always difficult and full of tension.

It is worth mentioning that, contrary to the image of the “detested tyrant” provided by the propaganda of the Entente allies for their national audiences, a large part of the Greek population adored and were devoted to King Constantine. These people believed that the King was sincerely interested in the well-being of his country and that he was keeping a delicate balance under pressure from both alliances to join their side in the war. King Constantine and his supporters often accused the Entente allies, especially France, of intervening in the internal affairs of Greece and of breaching Greek neutrality. Yet King Constantine was continuously suspected and accused by the Entente allies of having direct communication with and serving the interests of Germany, ruled by his brother-in-law Wilhelm II.

1916-17: Rise of tension between Constantine and the Allies. Dethronement of the King↑

The relations between Constantine and the Allies deteriorated further after May 1916, when Fort Rupel (in the eastern part of Macedonia) was surrendered to the Germans and Bulgarians. The Allies demanded the demobilization of the Greek army, which was considered a threat for the Allied troops in the region, and the cession of war material. The definitive rupture in the relations between Constantine and the Allies occurred in the first two days of December 1916, when military forces of the Entente disembarked in Piraeus and tried to control central points of Athens, involving themselves in violent and bloody clashes with troops loyal to the King; these events are known as the “Noemvriana” (November events). In retaliation the Allies imposed a tough naval blockade of Piraeus, which caused a large number of deaths (due to a shortage of food) in the Greek capital; they also requested the removal of the whole Greek army to the Peloponnese.

The stalemate in the Greek crisis was resolved by the decisive intervention of Great Britain and France in June 1917. King Constantine was obliged to retreat and leave for Switzerland; the throne passed to his son, Alexander, King of Greece (1893-1920). The violent dethronement of Constantine enraged his supporters and further deepened the hostilities over the next few months. Greek unity was not restored even after Venizelos returned to power and Greece officially entered the war. Followers of Constantine created a well-organized network of propaganda in Switzerland, making it more difficult for the Greeks to mobilize and, generally, for the country to participate in the war.

Last spell of Constantine on the Greek throne – Self-exile and death↑

After Venizelos’ defeat in the general election of November 1920, and as a result of a subsequent referendum, King Constantine returned to Greece to resume his royal duties on 19 December 1920. The Entente allies were not happy to hear this news. Not having forgotten his attitude during the war, they never officially recognized his return to the throne. In 1921 King Constantine opted for the continuation of the Asia Minor campaign, despite the objections expressed both inside and outside Greece. After the Asia Minor front collapsed and control passed to a revolutionary committee headed by colonels Nikolaos Plastiras (1883-1953) and Stylianos Gonatas (1876-1966), Constantine abdicated and went into self-exile in Palermo, Sicily, where he died a few months later, on 11 January 1923. Constantine I is regarded as one of the most controversial leaders in modern Greek history – he was both very much loved and very much hated by sections of the Greek population. Despite his controversial role, through both his actions and omissions he played a crucial role in the history of the country during the first decades of the 20th century.

Elli Lemonidou, University of Western Greece

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Selected Bibliography

- Constantine, King of the Hellenes: A king's private letters, being letters written by King Constantine of Greece to Paola, princess of Saxe-Weimar during the years 1912 to 1923, London 1925: E. Nash & Grayson.

- Leon, George B.: Greece and the First World War. From neutrality to intervention, 1917-1918, Boulder; New York 1990: East European Monographs; Columbia University Press.

- Leon, George B.: Greece and the Great Powers, 1914-1917, Thessaloniki 1974: Institute for Balkan Studies.

- Mélas, George M.: Ex-King Constantine and the War, London 1920: Hutchinson & Co.

- Theodoulou, Christos A.: Greece and the Entente, August 1, 1914-September 25, 1916, Thessaloniki 1971: Institute for Balkan Studies.