Background↑

Louis Botha (1862-1919) came to prominence during the Anglo-Boer (South African) War of 1899-1902 when he became commander of the Transvaal Boer forces. Botha had received no training in military methods but proved himself an able strategist, tactician and leader of men. After Britain defeated the Boers and the Treaty of Vereeniging was signed, he continued to be seen as a leader speaking out on behalf of the Boers. When Britain awarded the ex-Boer colony a representative government in 1907, he developed a loyalty to the Empire which guided his actions as Prime Minister of a united South Africa from 1910 throughout the First World War.

South Africa’s entry into the war: rebellion↑

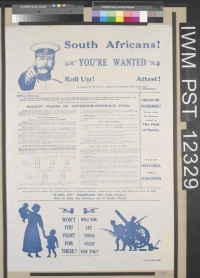

Botha’s first 1914 wartime challenge was to convince cabinet of the necessity of capturing neighbouring German South West Africa. Britain asked the Union to put the wireless stations out of action but Botha saw the opportunity to realise the long-desired British and Boer aim of incorporating the whole territory into South Africa. His cabinet was unanimously prepared to release the Imperial Garrison Troops to return to England but feared that attacking the German colony would split white South Africa, a section of which supported Germany due to its support of the Boer Republics during the 1899-1902 war. Fear of Australia or India being asked to undertake the task brought about agreement. Permission was then obtained from parliament which met following the new Governor General (and High commissioner) Lord Sydney Charles Buxton’s (1853-1934) arrival in September. The plans to invade the German colony, which had been hastily made, were actioned.

However, rebellion began almost immediately following the resignation of General Christiaan Frederik Beyers (1869-1914), head of the Permanent Force, and the accidental killing of Boer leader Koos De la Rey (1847-1914). De la Rey, regarded as the head of the anti-Empire Boers, saw the outbreak of war as an opportunity to regain Boer independence. De la Rey was killed on 15 September 1914 when the car that he and Beyers were driving in was shot at following their refusal to stop at a road blockade set up to capture a gang. The two men were on their way to a meeting to discuss future action with another rebel, General Jan Christoffel Gerhardus Kemp (1872-1946). De la Rey’s true position regarding the rebellion has never been fully identified but his death is seen as a significant milestone in the Boers’ descent into rebellion.[1] A month later, the rebellion became official when Solomon Gerhardus "Manie" Maritz (1876-1940) refused to entrain, entered the German colony and took prisoner those of his men who refused to support Germany.

Action against the German colony was put on hold whilst Botha personally led loyal volunteers against the rebels. He refused assistance offered by Britain, noting that the rebellion was between brothers and had to be resolved internally. By December, the rebellion was over.

South West Africa↑

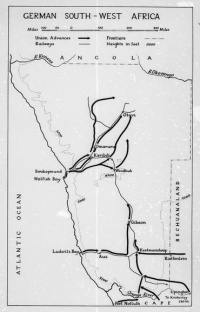

Botha then turned to the campaign against German South West Africa. This would be the first time British, mainly naval, and Boer military traditions would work alongside each other. In this, Botha, supported by Buxton, played an instrumental part. He appointed himself commander-in-chief of the German South West Africa expedition, much to the annoyance of his cabinet, which was concerned for his personal safety, and personally led the main striking force. Botha believed he was the only person who could unite both the English and Afrikaans (Boer) sections of the population. On 9 July 1915, the German forces surrendered to Botha.[2]

Election 1915↑

Tensions between the pro and anti-Empire factions remained high and despite requests by various people to postpone the election due in 1915, Botha insisted it take place. He wanted a mandate to continue his policy. Although reluctant to publicly commit South African forces to any other theatre of war, he allowed discussions to take place over contingents for Europe and East Africa. Recruitment was permitted for the Western Front as it would comprise white volunteers requested by and paid for by Britain. Under General Henry Timson Lukin (1860-1925), they served first in Egypt and then on the Somme.[3]

Botha won the October 1915 election with a reduced majority due to the rise of the National Party, which had tacitly supported the rebels. This allowed the recruitment of troops for East Africa and by February 1917 over 10,000 South African troops were fighting there under the command of General Jan Christian Smuts (1870-1950). They, too, were Imperial troops paid for by Britain. Smuts’ appointment had been delayed from October, when it was felt that the political situation in South Africa was too sensitive and that he should remain in the Union to support Botha. General Sir Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien (1858-1930) was appointed instead. However, when the latter fell ill and the situation in the Union eased, Smuts was free to go.

South Africa in Europe, East Africa and Palestine↑

In mid-1916, Botha took a break from politics and visited the troops in East Africa. During this time, the strategy changed from one of set battles to more mobile warfare. Although difficult to prove the extent of Botha’s influence in this connection, the timing, his astute military awareness, as well as his relationship with Smuts suggest he played a part. Botha was one of the few people who could get Smuts to change his mind.

In early 1917, David Lloyd George (1863-1945) became British Prime Minister and called the Empire representatives together. Botha sent Smuts to represent the Union because he was better suited to deal with legal matters and was more comfortable speaking English. Botha was concerned that if he personally left the Union for too long, further uprisings could occur. Botha’s main aims were 1) to unite the disparate white groups in the Union, and 2) to support the British war effort during the war. This entailed reducing opportunities for the Nationalists to accuse the Prime Minister of neglecting his own people. In this Botha was supported by Buxton, who mediated with the British government to pay for forces and supplies.

In addition to the forces sent to Europe and East Africa, Botha was involved in raising a labour contingent for service in Europe. The result was the South African Native Labour Corps (SANLC), which included men from South Africa, as well as the neighbouring protectorates.[4] When the SS Mendi, a troop carrier carrying a contingent of SANLC men, sank off the Isle of Wight, Botha, as Prime Minister and Minister for Native Affairs, wrote letters of condolence to the families and the House of Assembly stood in silence as a mark of respect.[5] Soon after, the SANLC was withdrawn from Europe, as the "experiment" had not been as successful as initially anticipated. South African labour and troops were also to see service in Palestine from mid-1917.

Peace talks↑

Following the armistice in 1918, Botha joined Smuts in London and Paris to ensure the Union received due recognition for its contribution to the war. Botha reportedly did not say much during the discussions, leaving the negotiations to Smuts. However, when the talks stalled over the mandate system, Botha made what was regarded by the Empire Delegation as his most valuable contribution. He noted that one had to give way in the small things in order to achieve a greater good. With this in mind, he would forgo complete annexation of German South West Africa in favour of a mandate to ensure that the remaining peace discussions did not falter. With Botha compromising, Australia and New Zealand followed, allowing the discussions to continue.

Death↑

The strain of war and not having Smuts with him for much of the time had its effect of Botha, who was not in the best of health generally. He succumbed to the outbreak of influenza that swept the world at the end of the war and died in Pretoria on 19 August 1919. For Botha, signing the Treaty of Versailles was recognition that South Africa was a country in its own right.

Anne Samson, Great War in Africa Association

Section Editor: Michelle Moyd

Notes

- ↑ Smith, J. P.: Die dood van Generaal De la Rey, in Scientia Militaria 6/3 (1976), online: http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za/pub/article/view/849 (retrieved: 10 January 2015).

- ↑ Grew, E. S.: Field Marshal Lord Kitchener. His life and work for the Empire, volume 2, London 1916, p. 193, online: https://archive.org/details/fieldmarshallord02grewuoft (retrieved: 21 April 2015); Whittall, W.: With Botha and Smuts in Africa, London 1917, p. 151.

- ↑ Buchan, John: South African Forces in France, London 1920.

- ↑ Clothier, Norman: Black valour. The South African Native Labour Contingent 1916-1918 and the sinking of the Mendi, 1998.

- ↑ Sinking of a transport, in: Rand Daily Mail, 10 March 1917, issued by SAHA, online: http://sthp.saha.org.za/memorial/articles/parliment_pays_tribute.htm (retrieved: 1 November 2014).

Selected Bibliography

- Buxton, Earl: General Botha, London 1924: Murray.

- Engelenburg, F. V. / Smuts, Jan Christiaan: General Louis Botha, Pretoria 1929: Van Schaik.

- Samson, Anne: Britain, South Africa and the East Africa campaign, 1914-1918. The union comes of age, London; New York 2006: I. B. Tauris; St. Martins Press.

- Spies, S. B.: The outbreak of the First World War and the Botha government, in: South African Historical Journal 1/1, 1969, pp. 47-57.

- Whittall, W.: With Botha and Smuts in Africa, London; New York 1917: Cassell and Co.