Early Life↑

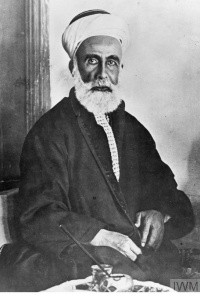

Shakib Arslan (1869-1946), Amir al-Bayān (Prince of Eloquence), was a prominent Arab politician and man of letters whose name became synonymous with the ideas of Panislamism and the anticolonial movement in the Muslim world during the interwar years. Arslan was born in Choueifat, a village in Coastal Mount Lebanon south of Beirut. The Arslans were one of the prominent Lebanese Druze families who governed parts of Mount Lebanon during the Ottoman period. Despite being born into the Druze heterodox faith, an off-shoot of Ismaili Islam, Shakib Arslan was strictly observant of Sunni Islam.

Like most of his peers, Shakib Arslan received his primary education from the local village Sheikh who taught Shakib and his older brother Nasib basic literacy and traditional Quranic studies. The two brothers later enrolled at the American School, set up by Protestant missionaries in the Arslans’ hometown of Choueifat. His education was augmented when he joined the Maronite Sagesse (Hikmah) School in Beirut in 1879. During his seven years at Sagesse, Arslan was taught by top-tier educators who gave him a strong literary command of both the French and Arabic languages.

After finishing his education at Sagesse, Arslan enrolled at the state-sponsored Madrasah al-Sultaniyyah in Beirut, which offered a solid training in Ottoman civil administration and related subjects. It was during this phase that Arslan became a student of the renowned Islamic reformer and intellectual, Muhammad Abduh (1849-1905). Abduh’s short stay in Beirut in 1887 gave the young Arslan the chance to interact with and frequent the former’s circles, transcending the traditional classroom. By becoming a disciple of Abduh and in turn Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1838-1897), he was indoctrinated into a class of young men who became preoccupied with finding answers to the challenges of the ever-changing political reality around them, primarily with regards to the Ottoman Empire and increasing western hegemony.

Career↑

Pre-World War I↑

Despite being groomed to take on governmental posts, Arslan was disenchanted with local Lebanese politics and chose to pursue a different path. He traveled throughout the region, strengthening his network of intellectual acquaintances and forming political and personal bonds with leading figures of the nahdah (Renaissance) movement. This network included figures such as al-Afghani, Ahmad Shawqi (1868-1932), Sa’d Zaghlul (1859-1927), Khalil Mutran (1872-1949), and Rashid Rida (1865-1935).

After 1908, the Young Turks, officially known as the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), were successful in restoring the Ottoman constitution. Consequently, Arslan was elected to the council of delegates representing the Hawran region. Originally branded as a monarchist, Arslan believed that the Sultanate was the symbol of Islamic unity and that it was his duty to support and maintain such an institution. Nevertheless, he would in time become a close ally and friend of the senior officers of the CUP, Ismail Enver Pasha (1881-1922), Mehmed Talat Pasha (1874-1921), and Ahmet Jamal Pasha (1872-1922). This friendship was to mature during Arslan’s participation in the Italian-Turkish War in Tripoli, Libya in 1911. While Arslan saw no active combat during this campaign, the eight months he spent on the frontline enhanced his image throughout the empire as well as his stature with the CUP officers who were slowly starting to control key parts of the Ottoman central government.

With the outbreak of World War I, Arslan, in contrast to many of his intellectual peers, sided with the Ottoman Empire. According to Arslan this was a fight between an Islamic Empire and a Western entity geared towards conquering and dividing Islamic lands. He became especially notorious for his opposition to the Arab Revolt under the leadership of Husayn ibn Ali, King of Hejaz (1853-1931) and for his whole-hearted support of the Ottoman war effort. Arslan also became a close associate of Jamal Pasha, who acquired the nickname “the butcher” for his brutal suppression of separatists in wartime in Syria. As he later professed in his memoirs, Arslan’s pretext for maintaining this relationship stemmed from his conception of his national duty to protect his compatriots by acting as a mediator between the masses and the Ottoman governor. He also explained that such a role was needed, especially with the famine in Syria caused by locust infestation. He never received recognition for this role, but instead was branded by the emerging Arab nationalist movement as a collaborator. However, with the defeat of the Ottoman Empire and its allies in 1918, it became clear to Arslan that he would no longer be welcomed in the Middle East, which was now under British and French control.

Post-World War I: A Champion of Pan-Arabism↑

Until the abolition of the Caliphate by Mustafa Kemal (1881-1938), Arslan lingered in Europe and Turkey hoping for the restoration of the Ottoman Empire. After it became apparent that this goal was unattainable, he refocused his activism to a more pressing matter, namely the French and the British domination and partition of the Arab world. Arslan however, was greatly ostracized from the ranks of the Arab nationalists he had formerly opposed. His transition into the ranks of the nationalists was made possible through the good offices of his close friend Rashid Rida, the renowned publisher of al-Manar. Rida was aware of his friend’s talents and thus brought him into the fold of the Arab cause. Arslan was quite successful in his new post as the head of the permanent delegation of the Syrian-Palestinian Congress to the League of Nations in Geneva. Through this delegation, Arslan and his companions were able to lobby for the demands of the so-called Arab Nation, such issues as the Great Syrian Revolt, and more importantly the question of Palestine. It was through the delegation’s publication Le Nation Arabe that Arslan bombarded European policy-makers as well as the general public with the demands of his political camp. While Arslan tried to be as diverse as possible in the articles he published in his journal and other prominent publications such as al-Manar, the Palestinian issue occupied a major share of his writings. This was mainly due to the fact that Arslan was a close ally of the Mufti of Jerusalem Hajj Amin al-Husayni (1895-1974); indeed, many believed that Arslan was in fact the Mufti’s main advisor.

Arslan’s encyclopedic knowledge and his vigor made him an icon to many political activists and movements throughout the Muslim world. Liberation movements in Tunisia, Libya, Morocco, and Algeria looked to Arslan and his writings as a base for their platforms and actions. Messali Hadj (1898-1974), one of the pillars of anti-French Algerian nationalism, viewed Arslan as his ideological guru. Moroccan nationalist leaders, such as Muhammad al-Wazzani (1910-1978), Ahmad Balafrej (1980-1990), and `Allal al-Fasi (1910-1974) were seen as Arslan’s spiritual disciples. This was equally true for other nationalist activists in the above-mentioned countries.

With the advent of World War II, the Arabs generally looked towards the Axis, mainly Germany and Italy, to change what amounted to Franco-British occupation of their lands. Shakib Arslan had maintained relations with the Axis countries, which shared his anticolonial aspirations. Arslan had good relations with Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) even before the latter assumed power. With the exception of his harsh criticism of Italy’s Libya campaign, Arslan maintained a positive outlook on Italy’s role in the east. Arslan was also plugged into Wilhelmine Germany’s Foreign Service and orientalist academic circles. However, the eventual defeat of the Axis eclipsed both Arslan and the anticolonial movement, whose members were branded as collaborators, forcing them at times to withdraw from public life. Shortly after the end of the war in the fall of 1946, Arslan decided to return to the east. His trip home was to be his last as he passed away on 9 December 1946 at age seventy-six.

In one of his books, Our Decline and Its Causes, Arslan summarizes the life he had spent fighting for the Muslim nation. Much of what Arslan wrote throughout the years was an attempt to answer this question: why have the Muslims lost their place under the sun and how might this be reversed. Shakib Arslan’s life and career has been viewed by many with varying degrees of admiration and controversy. However, what remains certain is that Shakib Arslan's used his talents and connections in the context of his transnational activism to try and advance his plan for an Arab-Muslim renaissance.

Makram Rabah, Georgetown University

Section Editor: Abdul Rahim Abu-Husayn

Selected Bibliography

- Adal, Raja: Constructing transnational Islam. The east-west network of Shakib Arslan, in: Dudoignon, Stéphane A. / Komatsu, Hisao / Kosugi, Yasushi (eds.): Intellectuals in the modern Islamic world. Transmission, transformation, communication, London 2006: Routledge, pp. 176-210.

- Arslan, Shakib: Our decline. Its causes and remedies, Kuala Lumpur 2004: Islamic Book Trust.

- Arslan, Shakib: Sīrah dhātīyah (autobiography), Beirut 1969: Dār al-alīah.

- Cleveland, William L.: Islam against the West. Shakib Arslan and the campaign for Islamic nationalism, Austin 2011: University of Texas Press.