Introduction↑

Historiographically the role of the Italian press during the First World War has been by and large neglected. There is as yet no wide-ranging and systematic analysis of the topic, but only stray references within works of a more general character, devoted to the history of journalism or of the war itself. Yet this issue is by no means of negligible significance, given that in the aftermath of the outbreak of hostilities there was in Italy a truly luxuriant flowering of new daily and periodical publications, as the various inventories and catalogues published from the 1930s onwards have amply shown.[1]

In this context, by concentrating mainly on the sector of the daily press (which, more assiduously and effectively than the periodical press, was able to capture, absorb and channel the moods of national public opinion), this article endeavours to provide the crucial coordinates by which to understand the relationship established between information and censorship during the conflict. It shall also investigate the role of the supreme command, the modus operandi of journalists engaged at the front, and newspaper readers’ shifting perception of events as they unfolded.

The Year of Waiting↑

In Italy – a nation militarily tied to the Triple Alliance – in the aftermath of the outbreak of hostilities the organs of the press and public opinion were essentially divided into two camps: a neutral camp, politically supported by substantial segments of the socialist and catholic worlds and by a part of the liberal world, and an interventionist camp, to which democrats, radicals, republicans, revolutionaries, anarcho-syndicalists, nationalists, and some liberals belonged.

As far as the press was concerned, after the official declaration of neutrality of 2 August 1914, a fair number of the major liberal dailies – albeit with nuances and a degree of vacillation – aligned themselves with the government’s decisions, as did the catholic and socialist presses, although there were some exceptions and occasional differences of emphasis.

By the end of 1914 the two camps had become still more starkly opposed, in part because of the conversion to the interventionist cause of Benito Mussolini (1883-1945), the editor of Avanti!, the official organ of the Socialist Party (October 1914). After relinquishing control of the paper and being expelled from the party on 15 November 1914, Mussolini launched a daily, Il Popolo d’Italia, an expression of the most passionate and rhetorical interventionism. Thanks also to the support of the editor of the Resto del Carlino Filippo Naldi (1886-1972), the future Duce was backed financially in this venture by, among others, French political milieux and by certain Italian industrialists, including Giovanni Agnelli (1866-1945) and the Perrone family, who stood to benefit from the country’s entrance into the war and the resulting increase in military spending.[2]

In many respects, in the early months of the conflict the press served as the main litmus test for the division of the country into different camps. This was in part owing to the virulent tone adopted by the interventionist newspapers, which saw their circulation soar,[3] and which, as the months passed, also affected various traditionally more moderate publications, beginning with the Corriere della Sera, which became one of the main supporters of interventionism, as they too began to employ much the same nationalist rhetoric.

Although in the country at large the majority of the population was probably by no means in favour of war, many of these papers gained ground in bourgeois public opinion. Precisely their capacity to inflame hearts and minds and depict the war as a necessary act of ritual purification would bring about the resurrection of a country brought low by the shame of Adowa[4] and by the “shabby compromises” of the Giolittian Italietta.[5]

Information and Censorship↑

In March 1915 – two months before the country’s entrance into the war – the Chamber of Deputies (with the backing of Salvatore Barzilai (1860-1939), president of the National Press Federation, the main organisation representing Italian journalists, approved a number of restrictive measures “for the economic and military defence of the state”.[6] Subsequently the packet of measures – the future law n. 273 of 21 March 1915 – was approved by the Senate, to the plaudits of the major national newspapers.[7] A week later, a new decree was imposed, namely a ban on the publication of any news regarding troop movements for the period between 31 March and 30 June 1915. While certain foreign powers were unstinting in their efforts to induce the Italian newspapers to adopt a line favourable to them (for example, the German embassy in Rome lavished flattery and blandishments upon the Corriere della Sera,[8] on 23 May 1915 Italy signed a declaration of war upon Austria-Hungary, an act followed by the general mobilisation and the entrusting of military operations to General Luigi Cadorna (1850-1928).

Where control over information was concerned, Italy, like other nations involved in the conflict, acted from the outset to censor military news and to promote various forms of “patriotic orientation”, so as to forestall any temptations to indulge in defeatism and any attempts to undermine “national concord”. Such measures had in part already been tried during the Libyan War of 1911-1912, when telephonic and telegraphic censorship had been imposed and when a press and censorship office had been set up in Tripoli, in order to prevent the publication of military news deemed classified and confidential.[9]

Preventative censorship of the press and of telegraphic, radiotelegraphic, telephonic and postal communications was introduced through a series of decrees ratified on the day that war was declared - once again with the blessing of Salvatore Barzilai, who had taken care to invite the press corps to “respect, without limits or reservations, the bonds of national discipline.”[10] These decrees served, among other things, to deprive magistrates of the power to seize periodicals, this latter action becoming the exclusive prerogative of the government, through the Ministry of the Interior and the Prefectures.[11] Newspapers could no longer specify numbers of casualties or of prisoners taken, and appointments and rotations in the high commands, nor could they speculate about military operations. The only sources of information would be official bulletins issued by the supreme command.

The obligation to submit to the prefectorial censorship – at least one hour prior to publication – the proofs of every page of a publication often forced newspapers to appear with vast expanses of blank white space. Readers were therefore frequently led to entertain inordinate suspicions or fanciful speculations as to the news that might have been censored, and they might even be left with the impression that the only credible news items were the ones that had been suppressed.[12] In the early months of the conflict journalists were in fact not even permitted to be at the front. Indeed, when a few resourceful correspondents tried to reach the conflict zone, they were immediately expelled and rebuked by their own colleagues, who reminded them, in the light of the gravity of the occasion, of the need for “an austere discipline.”[13] Only from September 1915 were correspondents allowed to operate in the field. Regulations stipulated that when deployed on the Italian Front, no more than two journalists per newspaper would be permitted (even if such a limitation was in practice often circumvented, through the fact of some of them being directly answerable to the supreme command),[14] that they had to be at least forty years old and that the editors had to pay all their operational expenses. Their redeployment was determined by the supreme command itself, which was responsible for authorizing any movements they might make.

As mentioned previously, military censorship was likewise the exclusive prerogative of the supreme command. Initially it was very strict and invasive, and only after a few months did it become somewhat milder. This was in part because the top brass came in time to realise the importance of using journalists in the information services of the military chiefs of staff (as many as three journalists from the Corriere della Sera were, for example, attached to the special services of the supreme command) and as mediators between the demands of the military and the choices of the government with regard to supplies of weaponry and investment in technological innovations.[15] Moreover, the military high commands did come in time to understand just how hungry soldiers deployed at the front were for news and information.

Propaganda and Psychological Warfare↑

As has already been noted, after Italy’s entrance into the war, the professional duties of Italian journalists altered radically. While those in the confidence of the supreme command began in fact to assume responsibility for the drafting of official communications, formally signed by the commander of the forces in the field,[16] their role was rapidly transformed from that of being in charge of information to that of being in charge – “morally responsible” before the nation - of psychological warfare.[17]

All the main dailies sent celebrated reporters to the front,[18] who showed little compunction in following the orders of the military hierarchies, also taking on the role of relaying information between the military commands, the zones behind the front line, the forces deployed at the front and the country as a whole.[19] All of this unfolded while from their armchairs the respective editors – often informed about the real situation at the front through their correspondents’ “classified letters” – played, in agreement with the military top brass, the part of “authorized personnel”, serving the country and their own prestige.[20] From February 1916, a ban was introduced on the publication of photographs and drawings on a military theme without the preventative authorisation of the military censor, a measure that had an especially damaging impact upon periodical publications, in which the iconographic element was of such importance. One month earlier, and chiefly in order to facilitate relations between army and press and to promote the work of propaganda, a press office was established in Udine alongside the supreme command, entrusted initially to Colonel Nicola Vacchelli (1870-1932), and later to Colonel Eugenio Barbarich (1863-1931), to which war correspondents on the Italian Front were supposed to report.[21] The journalist and writer Ugo Ojetti (1871-1946) was given a prominent role within this office, and from April 1918 he became director of the Central Commission for Propaganda directed at the Enemy.[22]

As the months passed, the supervision of the soldiers’ personal correspondence also became particularly stringent, especially after the Russian revolution of February 1917 and the entrance of the United States into the conflict. The fear in fact was that these events might engender among citizens and among the troops themselves false expectations as to a swift end to the war.

What did Readers Know?↑

As could be expected, the fact of being at war deeply preoccupied readers, who turned en masse to the newspapers in order to slake their own thirst for information. The war, therefore, proved very profitable for the newspapers, notwithstanding the depletion of the editorial teams and the inevitable increases in publication costs on account of the high costs of retaining correspondents and of the increases in the prices of paper, ink and telegraph tariffs. All the main national dailies, in order to follow the conflict as closely as possible, employed prestigious external collaborators, including cartographers, experts in military strategy and in weaponry, in aviation and in naval matters.

Information as to what was really happening at the front, including the everyday dramas lived by the troops in the trenches, the numbers of dead and wounded, the bloody assaults and the brutal executions, or the instances of fraternisation with the enemy, was still very far from being readily available to public opinion, which was therefore all too prey to misinformation. During the war the newspapers also stopped printing any “domestic” news relating to parliamentary clashes, strikes and demonstrations in favour of neutrality, the sanitary conditions in the country at large, disruptions of public transport or breakdowns in the distribution of goods. Information relating to earthquakes or other natural or meteorological phenomena was also censored, in order to avoid spreading alarm among the population.[23] There was in this regard an anticipation of methods and procedures that would subsequently be reproduced on a broad scale by governments under fascist leadership. Among the major dailies belonging to the old neutralist camp, only the socialist Avanti! conducted with any degree of coherence a campaign against the capricious measures introduced at the social and political level on account of the state of war, not infrequently falling foul of government censorship as a consequence.

Journalists in the Trenches↑

In the long run, the presence of a multitude of war correspondents who were disciplined and prepared to abide by the wishes of the supreme command – and the prevalence in the papers of rose-tinted correspondence from the front, in which the valiant offensives of the national troops were celebrated and in which nothing whatsoever was said about real conditions in the trenches – ended up causing serious unrest in the ranks. The quip directed at the correspondent for the Corriere della Sera, Luigi Barzini, (“if I see Barzino [sic] I’ll shoot him!”), attributed to an Italian infantryman stationed at the front, captures very well the unease that was felt at a patriotic rhetoric that was proving as the months passed ever less tolerable.[24] The political and military top brass were very slow to appreciate the anguish and the psychological needs of the rank and file, even though from July 1915 – at the urging of General Cadorna, who was concerned with the distress of ordinary soldiers – the censorship of letters sent to families had been temporarily suspended.[25]

From a political perspective, the generally indulgent attitude of the newspapers towards the executive was constantly fuelled – apart from threats of censorship – by sums of money lavished through the so-called “secret accounts”, as a dedicated parliamentary commission of enquiry, set up after the end of the conflict, would amply demonstrate. This practice – already current in the previous decades – was based upon the existence, at the very top of the Ministry of the Interior, of a fund used to subsidise, according to entirely discretional criteria, “friendly” newspapers and journalists. As for the abovementioned journalists deployed at the front, countless memoirs now enable us to give a full account of their feelings of disquiet at having, for more than three years, to compare public truths and private realities, conscious falsehoods and measured silences, always treading a fine line between information and propaganda.

After Caporetto↑

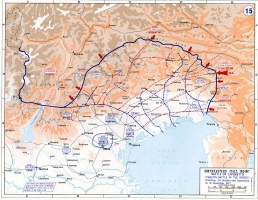

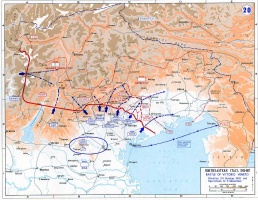

In the days following the breech in the Italian Front on 24 October 1917 the Italian war correspondents were immediately pulled back to Udine (and then, from 25 October, to Padua), so that they were materially prevented from closely following military operations. The immediate assumption, on the part of the supreme command, of the responsibility for furnishing whatever information was available on the recent military engagements naturally produced an almost total silence, which ended up fostering in public opinion every sort of suspicion or inference. Only at the end of November, once the requisite arrangements had been put in place by the new commander of the troops in the field, General Armando Diaz (1861-1928), were the correspondents’ stories once again printed on a more or less regular basis, when the authorisation was given for the sending of daily dispatches shorn of pointless rhetoric and of no more than 500 words.[26]

In the meantime, with the accession to power of Vittorio Emanuele Orlando (1860-1952), an undersecretariat for foreign propaganda and for the press was set up by law (Regio decreto numero 1817) on 1 November 1917 within the Ministry of the Interior. The new agency, directed by the honourable Romeo Adriano Gallenga Stuart (1879-1938), replaced the toothless department for propaganda without portfolio, created the year before and superintended by Vittorio Scialoja (1856-1933).[27] Giuseppe Antonio Borgese (1882-1952) took charge of the office for information and news, which formed an integral part of the new undersecretariat. It was therefore only after the defeat of Caporetto in October 1917, which led to the Austro-German invasion of over 20,000 square kilometres of Italian territory, that the supreme command made any attempt to exploit in a more extensive fashion the propagandist potential of the press, not least to boost the morale of the troops and to undermine that of the enemy.[28] Hence also the introduction of the so-called "P service" at the beginning of 1918 with emanations in all the commands, from armies to companies, from whose activities there sprung the “trench newspapers,” which in some cases emerged spontaneously even before Caporetto, on the initiative of individual soldiers. Such periodical publications, produced by the various armies and generally delivered to infantrymen at the front along with their correspondence,[29] boasted titles featuring references to battle and to patriotic sentiments, such as La Tradotta, L'Astico, Resistere, La Trincea, and Sempre Avanti. Various prominent intellectuals collaborated, as did well-known artists, such as Giorgio De Chirico (1888-1978), Giuseppe Ungaretti (1888-1970) and Mario Sironi (1885-1961).

Among the officers responsible for propaganda and employed in “P service” were indivuals who would later become well-known intellectuals, including Gioacchino Volpe (1876-1971), Giuseppe Lombardo Radice (1879-1938), Giuseppe Prezzolini (1882-1982), Piero Calamandrei (1889-1956), Massimo Bontempelli (1878-1960), and Alfredo Rocco (1875-1935).

In conclusion, in the days of Caporetto the Italian dailies offered no more than a very blurred image of the drama of the retreat. Only as the weeks passed, and the traumas and silences of those painful days were in part absorbed, did the press seek to convey a new mood of national-patriotic populism. All those professionally engaged in the imparting of information did in the end play a notable part in the creation of this new mood, sometimes out of “genuine conviction”, sometimes in a spirit of obedience, and finally sometimes out of pure “cynicism”.[30] Patriotic rhetoric was at its most inflamed from August 1918 onwards, with the approach of the grande battaglia of Vittorio Veneto, when all the newspapers engaged in a war of words inspired by a revived national concord, at the same time setting aside once and for all the dissatisfaction and dismay at the informational paralysis experienced up until then.[31]

Conclusion↑

Propaganda, combined with censorship, was indeed one of the genuinely novel facets of the First World War, when controls over the flow of information were on a larger scale than ever before, and sometimes involved recourse to techniques derived from the psychology of communication. Many governments recruited intellectuals and journalists with this end in mind, even going so far as to embrace new methodologies pioneered in the commercial arena. In this sense, the grande guerra also represented a huge international “public relations event” and proof as to how all the major nations had by this date become fully aware of all the advantages to be derived from an astute manipulation of information.[32] However, Italy was by and large slower to grasp the importance of propaganda.

As in other countries, the Italian newspapers only documented in a very partial fashion the drama of the trenches, the violence of the battles, the incompetence of officers, the desertions, the firing squads, and the instances of fraternisation with the enemy. The parliamentary commission of enquiry, set up in Italy on 12 January 1918 in order to investigate the causes of the retreat of Caporetto, significantly enough emphasised the war correspondents’ counterproductive role – as far as the morale of troops and officers was concerned. This had particularly been the case in the early phases of the war, when, even allowing for the difficult circumstances, journalists were never really able to provide a convincing narrative of the drama of the war, they proved to be all too willing to acquiesce in whatever the upper echelons of the military asked of them.[33]

As has already been noted, this article has addressed a predicament that Italy shared with other countries involved in the conflict. However, it was certainly exacerbated, in the peninsula, by the deep rift that had manifested itself from the outset between the interventionist and the neutral camp, and that had not been entirely healed even during the war. This was indeed a breach that, in the country’s weak ruling class, produced intense and enduring fears of a drift into defeatism.

Mauro Forno, University of Turin

Section Editor: Nicola Labanca

Translator: Martin Thom

Notes

- ↑ By way of example, see a recent compilation: Cavallo, Maria Lucia and Tanzarella, Ettore (eds.): Periodici italiani 1914-1919, Biblioteca di storia moderna e contemporanea, Rome 1989.

- ↑ Giacheri Fossati, Luciana and Tranfaglia, Nicola: La stampa quotidiana dalla Grande guerra al fascismo. 1914-1922, in Castronovo, Valerio/ Giacheri Fossati, Luciana/Tranfaglia, Nicola (eds.): La stampa italiana nell'età liberale, Rome-Bari 1979, p. 343; Pedio, Alessia: Costruire l’immaginario fascista. Gli inviati del «Popolo d’Italia» alla scoperta dell’altrove (1922-1943), Turin 2013, pp. 17ff.

- ↑ On these aspects see for example Giacheri Fossati and Tranfaglia, La stampa quotidiana 1979, pp. 265ff.; Castronovo, Valerio: La stampa italiana dall’Unità al fascismo, Rome-Bari 1970, p. 230.

- ↑ The Battle of Adwa was fought on 1 March 1896 near the Ethiopian town of Adwa between Italian forces and the army of Menelik II, Negusa Nagast of Ethiopia (1844-1913). For the first time a European army was defeated by an African army and this was seen as a disgrace by public opinion in Italy.

- ↑ Isnenghi, Marco: Il mito della grande guerra. Da Marinetti a Malaparte, Bari 1970, passim.

- ↑ Acts of Parliament of the Kingdom of Italy (XXIV legislature - Chambers of Deputies and Senato.

- ↑ Fiori, Antonio: Il filtro deformante. La censura sulla stampa durante la prima guerra mondiale, Rome 2001, pp. 56-64.

- ↑ Tartaglia, Giancarlo: Un secolo di giornalismo italiano. Storia della Federazione nazionale della stampa italiana, I, 1877-1943, Milan 2008, pp. 180-185 and 224-230.

- ↑ Fiori, Antonio: La censura durante la guerra di Libia, in Clio, 3 (1990), p. 486.

- ↑ See Un appello alla stampa italiana, in: Bollettino della Federazione della Stampa, 5, 25 May 1915, p. 1.

- ↑ Fiori, Il filtro deformante 2001, pp. 70-77.

- ↑ Vanzetto, Livio: Buona stampa, in Isnenghi, Mario and Ceschin, Daniele (eds.): La Grande Guerra. Uomini e luoghi del '15-18, Turin 2008, table 2, pp. 807-809; Fiori, Il filtro deformante 1990, pp. 453-456; Tartaglia, Un secolo 2008, p. 187.

- ↑ Tartaglia, Un secolo 2008, p. 194. Albertini’s legendary Corriere della Sera was in fact as vehement as any other newspaper in calling for a stringent censorship; see Tosi, Luciano: La propaganda italiana all’estero nella prima guerra mondiale. Rivendicazioni territoriali e politica delle nazionalità, Udine 1977, p. 37; Benadusi, Lorenzo: Il «Corriere della Sera» di Luigi Albertini. Nascita e sviluppo della prima industria culturale di massa, Rome 2012, pp. 272ff.

- ↑ Licata, Glauco: Storia e linguaggio dei corrispondenti di guerra, Milan et al. 1972, p. 124.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 117 and 124.

- ↑ Journalists on the Corriere della Sera were especially prominent in this regard; see Benadusi, Il "Corriere della Sera" 2012, p. 243.

- ↑ Isnenghi, Mario: Le guerre degli italiani. Parole, immagini, ricordi. 1848-1945, Milan 1989, pp. 171ff.

- ↑ The Corriere della Sera chose Luigi Barzini senior (1874-1947), the Secolo Rino Alessi (1885-1970), the Gazzetta del Popolo Mario Sobrero (1883-1948) and the Giornale d’Italia Achille Benedetti (1881-1951).

- ↑ Isnenghi, Le guerre 1989, pp. 171-172.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 175.

- ↑ Melograni, Piero: Storia politica della grande guerra. 1915-1918, Bari 1969, pp. 178-180.

- ↑ Tosi, La propaganda 1977, pp. 25 -33.

- ↑ Fiori, Il filtro deformante 2001, pp. 149-160.

- ↑ Alvaro, Corrado: Luigi Albertini, Rome 1925, pp. 34-35.

- ↑ Giacheri Fossati and Tranfaglia, La stampa quotidiana dalla Grande guerra al fascismo 1979, p. 285.

- ↑ Licata, Storia e linguaggio 1972, p. 125.

- ↑ Tosi, La propaganda 1977, pp. 152ff.

- ↑ On this particular aspect see Gatti, G. Luigi: Dopo Caporetto. Gli ufficiali P nella Grande guerra: propaganda, assistenza, vigilanza, Gorizia 2000.

- ↑ Isnenghi, Mario: Giornali di trincea (1915-1918), Turin 1977.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 65.

- ↑ The great battle, described by the war correspondents as an exclusively “Italian” victory, was celebrated by the newspapers less for its military aspects than for its civic consequences: for the feelings of joy, heartfelt emotion and gratitude it produced in the “liberated brothers”. On this theme see Ceschin, Daniele: Retorica della guerra e retorica della vittoria. La stampa italiana durante la battaglia, in Cadeddu, Lorenzo and Pozzato, Paolo (eds.): La battaglia di Vittorio Veneto. Gli aspetti militari, Udine 2005, pp. 229-240.

- ↑ Gibelli, Antonio: La Grande Guerra degli italiani. 1915-1918, Florence 1998, p. 240.

- ↑ De Simone, Cesare: L’Isonzo mormorava. Fanti e generali a Caporetto, Milano 1995, pp. 159ff.

Selected Bibliography

- Albertini, Luigi: Epistolario, 1911-1926, Milan 1968: A. Mondadori.

- Alessi, Rino: Dall'Isonzo al Piave. Lettere clandestine di un corrispondente di guerra, Milan 1966: Mondadori.

- Della Volpe, Nicola: Esercito e propaganda nella grande guerra, 1915-1918, Rome 1989: Stato Maggiore Esercito, Ufficio Storico.

- Esercito, R.: Norme per i corrispondenti di guerra. Prescrizioni per il servizio fotografico e cinematografico, Rome 1916: Laboratorio tipo-litografico del Comando Supremo.

- Fiori, Antonio: Il filtro deformante. La censura sulla stampa durante la prima guerra mondiale, Rome 2001: Istituto storico italiano per l'età modernae contemporanea.

- Forno, Mauro: Informazione e potere. Storia del giornalismo italiano, Rome; Bari 2012: Laterza.

- Gatti, Gian Luigi: Dopo Caporetto. Gli ufficiali P nella grande guerra. Propaganda, assistenza, vigilanza, Goricia 2000: LEG.

- Giacheri Fossati, Luciana / Tranfaglia, Nicola: La stampa quotidiana dalla grande guerra al fascismo 1914-1922, in: Giacheri Fossati, Luciana / Tranfaglia, Nicola / Castronovo, Valerio (eds.): La stampa italiana nell’età liberale, Rome; Bari 1979: Laterza, pp. 239-277.

- Gibelli, Antonio: La grande guerra degli italiani, 1915-1918, Milan 1998: Sansoni.

- Isnenghi, Mario: Giornali di trincea, 1915-1918, Turin 1977: G. Einaudi.

- Isnenghi, Mario: Le guerre degli italiani. Parole, immagini, ricordi 1848-1945, Milan 1989: A. Mondadori.

- Isnenghi, Mario / Rochat, Giorgio: La grande guerra, 1914-1918, Scandicci 2000: La nuova Italia.

- Licata, Glauco: Storia e linguaggio dei corrispondenti di guerra, Milan 1972: Guido Miano.

- Marchetti, Tullio / Museo trentino del Risorgimento e della lotta per la libertà: Ventotto anni nel servizio informazioni militari (esercito), Trento 1960: Museo del Risorgimento e della lotta per la libertà.

- Masau Dan, Maria / Porcedda, Donatella (eds.): L' arma della persuasione. Parole ed immagini di propaganda nella Grande Guerra, Gorizia 1991: Edizioni della laguna.

- Mondini, Marco: Parole come armi. La propaganda verso il nemico nell'Italia della grande guerra, Rovereto 2009: Museo storico italiano della guerra.

- Monticone, Alberto: La Germania e la neutralità italiana, 1914-1915, Bologna 1971: Il Mulino.

- Ojetti, Ugo / Ojetti, Fernanda: Lettere alla moglie 1915-1939, Florence 1964.

- Pettorelli Lalatta, Cesare: ITO. Note di un capo del servizio informazioni d'armata, 1915-1918, Milan 1931: Agnelli.

- Riosa, Alceo (ed.): Milano in guerra, 1914-1918. Opinione pubblica e immagini delle nazioni nel primo conflitto mondiale, Milan 1997: Edizioni Unicopli.

- Rossini, Daniela (ed.): La propaganda nella Grande guerra tra nazionalismi e internazionalismi, Milan 2007: Unicopli.

- Tosi, Luciano: La propaganda italiana all'estero nella prima guerra mondiale. Rivendicazioni territoriali e politica delle nazionalità, Udine 1977: Del Bianco.

- Zadra, Camillo / Labanca, Nicola: Costruire un nemico. Studi di storia della propaganda di guerra, Milan 2011: UNICOPLI.