Background and Historiography↑

General Evaluations↑

Beginning in September 1918, the Hapsburg Monarchy’s position worsened, even though this apparently did not negatively impact the Austro-Hungarian armies deployed along the south-western front. The Italian government and Ferdinand Foch (1851-1929) tried repeatedly to incite Armando Diaz (1861-1928) to organize an offensive between Monte Pasubio and Asiago to take advantage of Austria’s internal difficulties. According to the Italian chief of staff, such an attack would not have brought significant changes to the front line since the Italian army did not have enough divisions to perform an offensive in a mountain area. In fact, the Italian army could count fifty-seven divisions (among them three English, two French and one Czechoslovak) and 8,900 artillery pieces, versus fifty-eight Austro-Hungarian divisions and 7,000 artillery pieces.

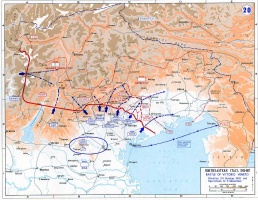

Therefore, Diaz planned in September-October an offensive along the Piave River where it was much more advantageous to station troops. Indeed, between Vidor and Grave di Papadopoli, there were twenty Italian divisions and 4,130 artillery pieces versus twelve Austro-Hungarian divisions and 1,000 artillery pieces. Furthermore, a successful attack in this zone would have allowed the Italian army to cut the supply lines of the Austrian Sixth Army and of the Armeegruppe Belluno.

Bad weather conditions postponed the offensive until 24 of October and necessitated the aid of the 4th Italian army.

Historiography↑

Analysis of the historiography is quite a difficult task because of the different evaluations of the importance of the Battle of Vittorio Veneto. Some analysts place emphasis on the simultaneous collapse of the Hapsburg Monarchy and describe this battle as an unsurprising victory; moreover, the breakdown of the Balkan front in September-October 1918 would have made the Italian contribution to the collapse negligible. Other authors even deny Vittorio Veneto’s status as a battle, considering the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian army as independent from the Italian intervention. In this view the Italian army had simply exploited this unprompted retreat. Still, the Italian historiography most often exaults this battle as the turning point of the war narrative: the victory at Vittorio Veneto counterbalanced the defeat at Caporetto and restored the army’s honor – of course reducing the role of the English and French divisions.

Most of these evaluations represent only a nationalist point of view. The battle dynamics are indeed much more complex and not given to mono-causal explanations.

The Battle↑

Svetozar Boroević von Bojna (1856-1920) did not expect an Italian attack along the Piave because of the floods that occurred in this zone after 16 October 1918. Moreover, he believed that the internal struggle of the Austro-Hungarian Empire would not impact the front: although the soldiers were exhausted because of the lack of food supply, the spirits and the reliability of the troops appeared good. In any case, he could count on ten reserve divisions behind the front line. These troops, in contrast with the soldiers deployed along the front, were troubled by the news coming from the Hinterland.

Since the overflowing of the Piave River did not seem to be stopping, on 24 October Diaz ordered the 4th Army to attack the Austro-Hungarian lines on Monte Grappa. On 26 October the Italian 4th Army was not able to move forward and the Austro-Hungarians counterattacked. Therefore, Diaz commanded the start of the offensive on the Piave: the goal of the 12th, the 8th and 10th Armies was to create three bridgeheads on the eastern bank of the river near Valdobbiadene, Sernaglia and Grave di Papadopoli. Except for the 11thHonvéd cavalry division whic refused to fight near Sernaglia, the others Austro-Hungarian troops kept their discipline and blocked Italian movement just beyond the river aided by the floods. Only beyond Grave di Papadopoli was the 10th Italian army ‒ composed of two English and two Italian divisions and headed by Frederick Rudolph Lambart, Earl of Cavan (1865-1946) ‒ able to create a small but significant break in the Austrian lines.

The turning point of the battle came with the decision taken on the evening of 27 October by Enrico Caviglia (1862-1945) to exploit this small bridgehead, displacing two fresh divisions from the 8th to the 10th Army so as to cut the communication between the 6th Austrian army and the Isonzoarmee. Meanwhile, Boroević tried to relocate his reserve near the front but both the distance and, above all, the unreliability of these troops prevented him from stopping the 10th Italian army’s advance. In fact he could relocate only six reserve divisions because most of the Hungarian, Czech, Slovenian and Croatian soldiers of the reserve refused to obey orders. Therefore, after the failure of the counterattack of 28 October, the Austrian defensive situation worsened and other reserve units decided to desert the front.

At last, the Austro-Hungarian high command ordered a general retreat and organized an armistice commission which contacted the Italian army on 29 October. Meanwhile the 8th Italian army exploited the breakthrough of the 10th Army and advanced in the direction of Vittorio Veneto, reaching the city on 30 October. At that point, the Austro-Hungarian army was split in two and the Italian high command ordered an attack on the other front zones to exploit the retreat. On the afternoon of 3 November the Italian troops had reached Trento and Trieste and at 3:20 p.m. in Villa Giusti the armistice was signed to become effective twenty-four hours later, at 3:00 p.m. on 4 November.

Conclusion↑

The Battle of Vittorio Veneto cannot be described as a spontaneous retreat of the Austrian army, at least until 30 October. The Austro-Hungarian troops deployed along the front line had been fighting fiercely, above all at Monte Grappa where the Italians counted 28,000 casualties in six days. Moreover, the Italian and Austrian generals were not expecting a rapid breakdown of the Austrian army before the battle.

Nevertheless, the Austrian reserve units felt the effects of the internal situation in the Austrian state and refused in many cases to obey orders, preventing a successful counterattack at Grave di Papadopoli. This element turned out to be decisive in allowing the Italian 8th Army to reach Vittorio Veneto and divide in two the Austrian army.

In conclusion, the Battle of Vittorio Veneto could be described as the end of a war of attrition. The order of battle was well planned but the unwillingness of Austro-Hungarian soldiers to sacrifice their lives for a cause they did not perceive as their own was probably the key element that allowed the Italian army to transform a local breakthrough into a strategic advance.

Francesco Frizzera, University of Trento

Section Editor: Marco Mondini

Selected Bibliography

- Balla, Tibor / Cadeddu, Lorenzo / Pozzato, Paolo (eds.): La battaglia di Vittorio Veneto. Gli aspetti militari, Udine 2005: Gaspari.

- L'esercito italiano nella grande guerra, 1915-1918, volume 5, Rome 1988: Stato maggiore dell'esercito-Ufficio storico, 1988.

- Del Negro, Piero: Vittorio Veneto e l'armistizio sul fronte italiano, in: Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane / Becker, Jean-Jacques / Gibelli, Antonio (eds.): La prima guerra mondiale, volume 2, Turin 2007: Einaudi, pp. 339-350.

- Glaise von Horstenau, Edmund (ed.): Österreich-Ungarns letzter Krieg 1914-1918. Das Kriegsjahr 1918, volume 7, Vienna 1938: Militärwissenschaftliche Mitteilungen.

- Isnenghi, Mario / Rochat, Giorgio: La grande guerra, 1914-1918, Scandicci 2000: La nuova Italia.