Origins and First Edition↑

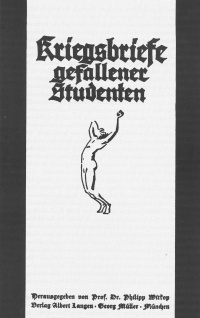

The First World War motivated numerous intellectuals to produce public statements supporting the nation at war, including poetry, speeches and articles. Philipp Witkop (1880-1942), a young professor of German literature, developed a new form within this wartime literature by collecting and publishing war letters sent from the front to those at home. Letters from the front had previously been published in Germany, but Witkop selected only letters written by students who had died in the war. First editions in small printings appeared during the war. In 1928, a considerably expanded (350-page) edition became a bestseller: hundreds of thousands of copies were sold until well into the Nazi era. Witkop created what was at the time the best-known and most popular collection of wartime letters as a historical source.

The first edition, with some 100 pages, was released in early 1916. It aimed to document students’ national patriotism. It was also intended to serve as propaganda in neutral countries and received state support (to fund translations into Swedish and Dutch, for example) that continued when new letters were later collected. In 1917, the universities aided Witkop in contacting the parents of all students killed in action, yielding some 20,000 letters (in 1914 about half of Germany’s 80,000 students became soldiers; by the end of the war about 20 percent of all students had died). This first edition, as well as the second, slightly expanded edition published in 1918, aroused little attention in Germany.

The Bestselling Edition of 1928↑

Witkop’s collection was effective due to its selective arrangement. The 1928 edition included letters from 120 students – who in some cases had written just one letter, and in other cases several letters, all ordered by the dates on which the writers had died. The collection thus represented first, “young people” and second, the intellectual elite serving their nation. The war letters were quoted as illustration and evidence of the purported purity of the young volunteers in numerous speeches held at university memorials commemorating former students. Because of the supposedly voluntary sacrifices made by young people in the war, it was often argued (not only in Germany) that the academic elite had a right to claim leadership positions. Together with the myth of Langemarck (November 1918), the war letters frequently represented, beginning in the late 1920s, the enthusiasm, the purity of self-sacrifice, and consequently the innocence of the German people so often evoked after 1918. This innocence also purportedly manifested itself in the “August Experience” and in the “spirit” of 1914. The war letters embodied the collective, the disappearance of the individual as part of the people as a whole, and also offered readers opportunities to identify with individuals. The result was positively received across the entire spectrum of political parties. The volume was read as testimony to the subjective war experience of the letter writers; the letters presented a moral interpretation of the war as a personal challenge, catharsis, and a test, ignoring political assessments and questions about the causes and motives. The selection and arrangement generated the image of an apolitical, ethical war experience, further enhancing the collection’s popularity and dissemination from the late 1920s on, and also leading to translations into the languages of the former war adversaries (English, French).

Manfred Hettling, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg

Section Editor: Mark Jones

Translator: Paula Bradish

Selected Bibliography

- Hettling, Manfred / Jeismann, Michael: Der Weltkrieg als Epos. Philipp Witkops Kriegsbriefe gefallener Studenten, in: Hirschfeld, Gerhard / Krumeich, Gerd / Renz, Irina (eds.): Keiner fühlt sich hier mehr als Mensch... Erlebnis und Wirkung des Ersten Weltkriegs, Essen 1993: Klartext, pp. 175-198.

- Ketelsen, Uwe-K.: 'Das ist auch so ein unendlicher Gewinn mitten in der Erfahrung des gräßlichsten Todes'. Arbeit an der Biographie. Philipp Witkops Sammlung von studentischen Briefen aus dem Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Josting, Petra / Wirrer, Jan (eds.): Bücher haben ihre Geschichte. Kinder- und Jugendliteratur, Literatur und Nationalsozialismus, Deutschdidaktik. Norbert Hopster zum 60. Geburtstag, Hildesheim; Zurich; New York 1996: G. Olms, pp. 51-61.

- Ulrich, Bernd: Die Augenzeugen. Deutsche Feldpostbriefe in Kriegs- und Nachkriegszeit 1914-1933, Essen 1997: Klartext Verlag.

- Witkop, Philipp (ed.): Kriegsbriefe gefallener Studenten (6 ed.), Munich 1933: Müller.

- Witkop, Philipp (ed.): Kriegsbriefe deutscher Studenten, Gotha 1916: F.A. Perthes a.-G..

- Witkop, Philipp (ed.): Kriegsbriefe gefallener Studenten (5 ed.), Munich 1928: U. Langen, G. Müller.

- Witkop, Phillipp (ed.): Kriegsbriefe gefallener Studenten, Leipzig 1918: B.F. Teubner.