General↑

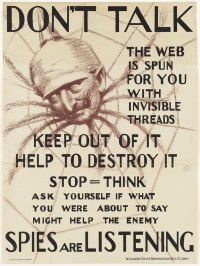

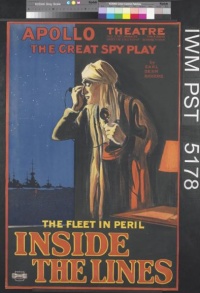

In the early days of World War I, a period of nervous waiting, the nationalism and propaganda fostered by both state and society in all war theatres created a breeding ground for collective myths. Many of these myths sought to personalise the enemy, especially the figure of the enemy spy. This fear rested on the notion that spies were allegedly everywhere within the nation, and yet also undetectable – constituting a dangerous and duplicitous internal enemy. This created a situation whereby all citizens could contribute to the national war effort and thus the greater good by remaining vigilant and fighting this threat. However, while spies seemed to be ubiquitous in the public mind and media, there were in reality very few convictions for espionage. The following section will focus on Spy Fever as it played out in the war theatres of Great Britain, the German Reich, France, and Russia.

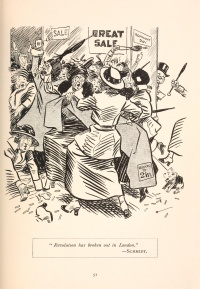

Spy Fever in Great Britain↑

Given its reputation as the home of spy fiction, British society was highly sensitized to the topic of espionage. Even before the war it was taken for granted that Germany had a highly developed espionage system, so when the war began the British public feverishly participated in the media hunt for German spies. Although none of the cases investigated turned out to be true, it took the British government nearly a month to deny multiple reports that the state had indeed found and executed spies. On the one hand, these anxieties must be understood against the background of a general invasion anxiety, as the German army was gaining ground quickly in Belgium and France. Yet on the other hand, a scapegoat was needed for the setbacks of the British army. This was found in members of the elite with an unknown origin or in artists seen as living a profligate life. But it was primarily the 50,000 people of German origin living in Britain who raised suspicion, leading to accusations of espionage, but also sabotage and food poisoning. Anti-German riots broke out in October 1914. The political right gave these images antisemitic connotations as well, so that “Germans, Jews and Spies became nearly synonyms”[1].

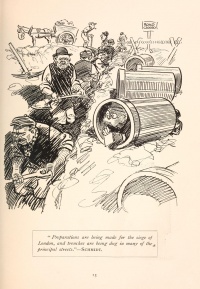

Spy Fever in the German Reich↑

The German authorities also believed in a general threat posed by spies. In the German Reich, the fear of omnipresent spies was promoted by the government as a measure to strengthen readiness for defence. One of the most common reports included “gold cars,” cars full of gold that the French military were allegedly driving through Germany to Russia for the war effort. Vigilance committees were created, which threatened drivers and hung metal wires across roads at night which became deadly traps. After almost a dozen people died, the German government finally denied the existence of the “gold cars,” but even this did not end the hunt. Spy Fever in Germany also included reports of poisoned food and water, sabotage, or the intentional spreading of diseases. In some cases local governments were compelled to prove that spies had not poisoned local water supplies by drinking it in ostentatious public displays. In many municipalities police were overwhelmed by reports of enemy aircraft sightings, as part of the German population was gripped by, as the Kölnische Volkszeitung stated critically, a “great, nearly frantically agitation”[2]. The main perpetrators were understood to be foreigners. It is remarkable that in 1914 groups already commonly perceived as internal enemies, such as Jews or organised workers, were not accused of espionage. Spy fever, although initially encouraged by the government, in fact spiraled out of control and became a hindrance to public order and the war effort. As in other locales, there were very few convictions, suggesting this was mainly an imaginary danger.

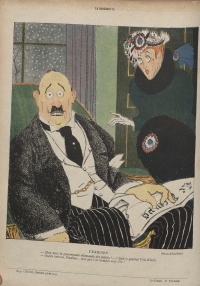

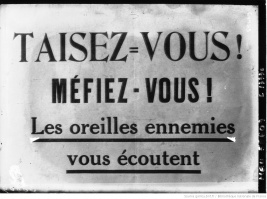

Spy Fever in France↑

As France was Germany’s main target at the beginning of the war, the central threat was perceived as German spies sabotaging war mobilization and supply lines. Spy Fever was mainly present in the first months of the war, fueled by the press. German companies operating in France were popular targets, accused of distributing rotten goods and holding back materials of military importance. German spies were alleged to have organised sabotage on railways or informed nearby German troops using light signals. In the first weeks of the war a wave of arrests targeting foreigners occurred, but no one was found guilty of espionage in the trials that followed. A few German shops were looted in Paris, but it was not a mass phenomenon. In the second half of August 1914, a panic broke out within the French government when the fall of Paris and occupation by German troops seemed imminent. The government proved highly willing to believe that spies were to blame for this situation and developed plans for evacuation in the last days of August and beginning of September 1914. This mixture of military defeats, the fear of Paris being captured, and losing the war created a widespread willingness to believe conspiratorial explanations for these events.

Spy Fever in Russia↑

Fear of espionage played a crucial role in Russia even before the war started. Russia’s defeat in the Russo-Japanese War was a key factor here, as it was widely understood to have resulted from sophisticated Japanese espionage. Shortly prior to World War I a law was passed that removed the right to a trial for suspected spies. When the war began, a massive Spy Fever broke out, mainly linked to antisemitism. Jews were viewed as disloyal to the Russian nation and were accused of collaborating with the enemy. However, German-speaking citizens, freemasons, and various other ethnic minorities were also targets, especially during riots. While Russian authorities were mainly interested in preserving order, the army often radicalized the media-fueled hunt for spies. Given nearly unlimited power when the war broke out, the Russian army deported internal minorities in large numbers without any judicial process.

Conclusion↑

Until the turn of the century espionage was understood to be a purely military matter. By World War I this had changed in several important ways. National intelligence agencies were established, leading to the professionalization of espionage. Around the same time, several spectacular espionage cases captured the popular imagination. This greatly contributed to a broader public interest in espionage and popularised the genre of spy fiction. In this “age of nervousness” (Joachim Radkau), the enemy spy consolidated all the anxieties of nationalist societies in wartime. Since Eigensinn – Alf Lüdtke’s (1943-2019) concept, which is commonly rendered in English as “stubbornness” – as a consequence and tool of nationalist ideologies, such as Spy Fever, can never be underestimated, it is also important to consider the ways in which the fear of the "internal enemy" was instrumentalized by interest groups for domestic political purposes. This is especially true for Germany, France, and Great Britain, but also for other belligerent and neutral countries in which similar phenomena occurred.

Sebastian Bischoff, Universität Paderborn

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Notes

Selected Bibliography

- Altenhöner, Florian: Kommunikation und Kontrolle. Gerüchte und städtische Öffentlichkeiten in Berlin und London 1914/1918, Munich 2008: Oldenbourg.

- Bavendamm, Gundula: Spionage und Verrat: konspirative Kriegserzählungen und französische Innenpolitik, 1914-1917, Essen 2004: Klartext.

- Becker, Jean-Jacques: 1914. Comment les Français sont entrés dans la guerre. Contribution à l'étude de l'opinion publique printemps-été 1914, Paris 1977: Presses de la Fondation nationale des sciences politiques.

- Boghardt, Thomas: Spies of the Kaiser. German covert operations in Great Britain during the First World War era, Baskingstoke 2004: Palgrave Macmillan.

- French, David: Spy Fever in Britain, 1900-1915, in: The Historical Journal 21/2, 1978, pp. 355-370.

- Lohr, Eric: Nationalizing the Russian Empire. The campaign against enemy aliens during World War I, Cambridge 2003: Harvard University Press.

- Sobich, Frank Oliver / Bischoff, Sebastian: Feinde werden. Zur nationalen Konstruktion existenzieller Gegnerschaft; drei Fallstudien, Berlin 2015: Metropol.