Anglo-German Antagonism↑

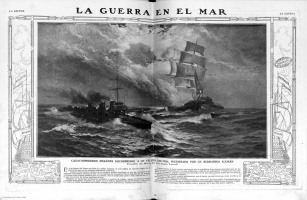

In August 1914 British naval centres undertook new duties connected with supplies and merchant transport. The Gibraltar Naval Intelligence commission was established to guarantee the export of Spanish raw materials for Allied war industries, especially iron ore and pyrites. To this end, British actions were mainly directed at: (1) inspection of ships in the Strait of Gibraltar; (2) interception of communications from the Spanish mainland and island ports; and (3) identification and weakening of German spy and sabotage rings. While Flag Captain John Harvey was responsible for the local flotilla and blockade actions, Major Charles Julian Thoroton (1875-1939) set up a mobile network of Royal Navy officers along the peninsula seaboard.

Meanwhile, the German embassy in Madrid, led by Prince Maximilian von Ratibor und Corvey (1856-1924), was already actively supporting sabotage plots against Allied economic interests in Spain. Britain’s arms industry heavily depended on Spanish iron ore deliveries; thus, German intelligence sought to cause early unrest in mines delivering to Great Britain, particularly in Rio Tinto Co.

Major Arnold Kalle (1873–1952) and Lieutenant Commander Hans von Krohn were in charge of German intelligence operations. Kalle had undertaken the position of military attaché at the German embassy in Madrid in April 1913, while Krohn was appointed on a special mission in September 1914. Their task was also to cause distress to friendly Allied relations with Spain. Funds available for certain campaigns reached as high as 1,000,000 pesetas (approximately 39,904 pounds sterling). Kalle and Krohn usually handled amounts much higher than the Allies could afford to bribe Spaniards for intelligence operations.

The Germans also carried out sabotage campaigns against the British-controlled Gibraltar and trafficked in arms contraband to Morocco. Additionally, their consulates on the sea coast provided the necessary information on local trade, shipping movements, dealers, and consignment agencies in British and French hands. The first steps forward in the quest for a British naval service in Spain mirrored the enemy breakthroughs.

Commercial intelligence↑

The Gibraltar Naval Intelligence Centre’s mission was to identify Spanish companies that traded with the enemy, with the ultimate goal of bringing German contraband to an end. British confidential blacklists soon spread out around Spanish ports: Vigo, La Coruña, Bilbao, Barcelona, Valencia, Cartagena, Malaga, and Seville. German commerce was soon cut off. On 20 July 1915, Thoroton forwarded his own network details to the Ambassador in Madrid, Arthur Hardinge (1859–1933). In due course British consular officers in Spain were instructed to cooperate and give Thoroton’s men all the facts or commercial information they possessed.

Juan March↑

The British Secret Service was set up in Spain to function autonomously, acting separately from the Foreign Office representation. The naval organisation had its own informants and field agents who — according to German espionage - could not easily be linked with the diplomatic agents. In those days Britain’s most valuable asset was the cooperation of Juan March (1880–1962). The famous Spanish tobacco smuggler, also known as Verga, was already working for the British in 1915. While he was running German reservists to Italy and supplying enemy submarines, March acted as a double agent. The smuggler handled complete and useful information of German covers and hiding places in Spain. He knew about the connivance of certain Spanish authorities, motor feluccas employed in enemy traffic, lawless crews, and depots where petrol was delivered in lots. The Majorcan billionaire’s loyalty to the British network proved long-lasting: March continued to render his valuable services to the British cause in the Second World War.

Interallied Quarrels: The French and the Italians↑

By December 1915, Lieutenant Robert de Roucy (1881-1919) was appointed naval attaché at the French embassy in Madrid to promote a secret service modelled on the British. At the same time, the Italians designated Lieutenant Commander Filippo Camperio (1873-1945) as naval attaché at the Italian embassy. Nevertheless, French and Italian hopes for British collaboration in secret missions were soon dashed.

Thoroton refused to share the advantage that his organisation had due to its early mobilisation in Spain. In May 1916, the head of the French Office of Naval Intelligence in Toulon complained bitterly about how the British concealed sources of information from him. Moreover, Thoroton hindered direct communications between Britain and the French and Italian heads of services. At that point, there was no British naval attaché in Madrid, though a permanent officer from the Admiralty, Lieutenant Oliver Baring, had been appointed at the embassy to serve as Thoroton’s liaison with other services. However, the French and the Italian naval attachés kept insisting that the British should appoint an elected delegate in Madrid. Finally, Flag Captain John Harvey left Gibraltar when he was designated as naval attaché in December 1917. One of Harvey’s main duties consisted of smoothing over interallied disputes.

Despite the difficulties collaborating with the British faced by the French naval attaché, the new service was in fact able to mobilise resources relatively quickly. Motivated by either pecuniary interest or patriotism, members of the large French community in Spain - consuls, business managers, directors of banks and mining companies - started to work for the naval organisation. In August 1917 Roucy was replaced by Lieutenant Commander Aristide Bergasse du Petit-Thouars (1872-1932). By then, a French plot related to the Spanish masons, most of who were republicans and sought to undermine the established political system in Spain, had been discovered and the blame was put on Roucy, which was an important factor leading to his replacement.

In the meantime, the Italians had more trouble setting up their organisation, given their smaller presence in the Spanish landscape and the limited funds available. However, they were still able to foster the development of their own networks all over the Spanish Levante.

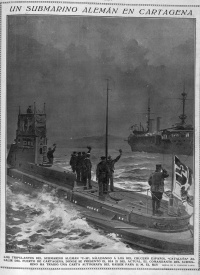

Canaris in Spain↑

Lieutenant Wilhelm Canaris (1887–1945) had been sent to Spain from Germany to support Krohn's service in 1916. Together with Albert Hornemann, Canaris organised a network consisting of an information service, agent service, and political news service. Spanish seamen, captains, and port authorities were recruited in the Spanish Levante to report on sailing activity. However, the efficiency of Canaris’s mission suffered because the British had already broken the German codes; Canaris, under the codename “Carl”, clearly became an Allied target. In October 1916 the German Admiralty sent the U-35 submarine to take him away from Spain.

The “Red Danger”↑

Counterespionage activities allowed the Allies to confront new, and many, challenges from Germany in 1917. The advent of unlimited submarine warfare called for intensified surveillance to hamper submarine supply bases on Spanish coasts. The Germans were very actively working on establishing secret fuel depots along the Spanish Mediterranean seaboard. Furthermore, the creation of a French Naval press office in Spain, connected to the French coastal intelligence service, was an example of the spread of the secret services work. Another front was the repression of strike activity. The German organisation, taking advantage of Spanish social unrest and instability, was infiltrating its agents in trade unions in the hope of learning about Allied logistics.

In response, the Anglo-French counter-espionage programme was mainly put into action to fight the Bolsheviks’ progress in Spain and to protect mining and industrial corporations like Río Tinto or Peñarroya. The Spanish General Directorate of Security actually exerted violent and repressive controls over individuals based on Allied recommendations. The powerful British secret service was further strengthened and kept after peace was reached, coinciding in Spain with the so-called “Trienio Bolchevique” (Bolshevik Triennium). However, the French sought to distance themselves from British methods of force because of their distinct perception of Spanish unrest: they thought that repression was far from being the only and most suitable means of solving the problem, which was not only connected with the German propaganda and espionage. Other causes included Spanish social and economic inequality, which had worsened by the conditions of the war. The French had started a propaganda campaign addressed at the working class.

Carolina García Sanz, Escuela Española de Historia y Arqueología en Roma

Section Editor: Ana Pires

Selected Bibliography

- Calvo-Sotelo, Mercedes Cabrera: Juan March (1880-1962) (1 ed.), Madrid 2011: Marcial Pons Ediciones de Historia.

- García Sanz, Carolina: British blacklists in Spain during the First World War. The Spanish case study as a belligerent battlefield, in: War in History 21/4, 2014, pp. 496-517.

- García Sanz, Fernando: España en la Gran Guerra. Espías, diplomáticos y traficantes, Barcelona 2014: Galaxia Gutenberg.

- González Calleja, Eduardo / Aubert, Paul: Nidos de espías. España, Francia y la Primera Guerra Mundial, 1914-1919, Madrid 2014: Alianza.

- Mueller, Michael: Canaris. Hitlers Abwehrchef, Berlin 2006: Propyläen.

- Rosenbusch, Anne: Los servicios de información alemanes. Sabotaje y actividad secreta, in: Andalucía en la Historia 45, 2014, pp. 24-29.

- Vickers, Philip: Finding Thoroton. The royal marine who ran British naval intelligence in the western Mediterranean in World War One, Southsea 2013: Royal Marines Historical Society.