Early Career↑

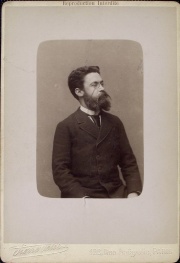

Marcel Sembat (1862-1922) was one of the leading French socialists of the pre-war years. Sembat, who was married to the well-known post-impressionist painter Georgette Agutte (1867-1922), was a very independent mind, highly intelligent and interested in the most various of subjects. Born to a provincial post officer, he studied law in Paris, but soon turned to journalism and politics. In 1890, Sembat became editor of the popular newspaper La Petite République, which he transformed into a mouthpiece of the socialist movement. Elected deputy of Paris in 1893 (and re-elected until his death), Sembat, a brilliant speaker, soon became one of the most prominent members of the socialist group in the Chambre des députés. In 1913, he published his famous and much-criticised book Faites un roi, sinon faites la paix, a passionate plea for peace in Europe and for a rapprochement between Germany and France. Compared to an authoritarian monarchy, Sembat claimed, a republic was structurally inferior in warfare; in the case of war, it would have to betray its own principles to not run the risk of defeat. Thus the preservation of peace was for the Republic (and all republicans like Sembat) a question of life or death. Sembat also criticised his own party for its belief in the legitimacy of a “defensive war”. In the heat of an international crisis and a tide of nationalist emotions, he stated, it would be impossible to decide which side was the “aggressor”: all citizens, socialists included, would enthusiastically go to war, convinced that theirs was a just cause.

Wartime Responsibilities↑

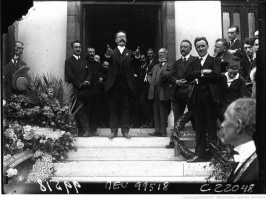

After the death of Jean Jaurès (1859-1914) in 1914 (which profoundly shocked Marcel Sembat, despite their sometimes divergent political views and styles), Sembat, as the most prominent remaining socialist, was appointed minister of public works in the first union sacrée government, with Léon Blum (1872-1950) as his principal chief of staff (chef de cabinet). In spite of the scepticism articulated in Faites un roi, sinon faites la paix, he now had no doubts that France was the victim of German aggression and thus was acting in self-defense.

Sembat took his office very seriously. Responsible for infrastructure and communication, he considered himself a “technical” minister whose duty was effective administration, not socialist transformation. He distinguished between the long-term goal of the revolutionary overthrow of capitalism and the short-term necessity of defending the nation’s independence. The main problem soon proved to be the coal supply, both for military means and private consumption. Since some of the most important French coal fields had fallen under German control, the country now depended more than ever on imports, particularly from the United Kingdom. As minister, Sembat found himself in a difficult position between the demands of the military, the needs of the general public, and the interests of the mine owners in France and abroad. Even if his actions were not unsuccessful, public opinion and parliamentarians made him and his ministry responsible for the various shortages in coal supply that occurred during the first two years of the war. In December 1916, Sembat, tired from the growing criticism, resigned from office. He nevertheless continued to support the union sacrée, convinced until the end that France was fighting a just war.

After the War↑

After the war, Sembat, despite his former revolutionary positions, found himself on the right-wing of his party. He shared neither the growing pacifism of many party members nor the enthusiasm created by the Bolshevik revolution in Russia. Consequently, in 1920, he refused to join the newly formed communist party and remained loyal to the old Section Française de l'Internationale Ouvrière (SFIO). Although he continued to serve as a deputy, he ceased to play an important role in post-war politics. Having already been in poor health for several years, Sembat died on 5 September 1922. His wife Georgette followed him by suicide only one day later.

Daniel Mollenhauer, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München

Section Editor: Emmanuelle Cronier

Selected Bibliography

- Chancerel, Pierre: Un socialiste à l’épreuve du pouvoir. Marcel Sembat, ministre des Travaux publics, in: Ducoulombier, Romain (ed.): Les socialistes dans l’Europe en guerre. Réseaux, parcours, expériences, Paris 2010: Harmattan, pp. 45-53.

- Grossheim, Heinrich: Sozialisten in der Verantwortung. Die französischen Sozialisten und Gewerkschafter im ersten Weltkrieg 1914-17, Bonn 1978: Neue Gesellschaft.

- Krumeich, Gerd: Marcel Sembat – ein Intellektueller als Sozialist, in: Krumeich, Gerd (ed.): Deutschland, Frankreich und der Krieg. Historische Studien zu Politik, Militär und Kultur, Essen 2015: Klartext Verlag, pp. 396-408.

- Lefebvre, Denis: Marcel Sembat. Socialiste et franc-maçon, Paris 1995: Graffic.